If you don't believe the rape victim, chances are you're wrong

People lie. We lie about liking our in-laws. We lie about our income. We lie to our parents about studying at the library when really we're smoking weed in the park.

These lies are common. A victim lying about rape is not.

Yet Rolling Stone decided Friday to distance itself from its widely read story about a violent sexual assault on the University of Virginia campus. The story, written by Sabrina Rubin Erdely, followed a survivor named Jackie. It documented the subsequent campus investigation into the fraternity brothers who allegedly raped Jackie in 2012.

Problem is, Rolling Stone never actually talked with those accused men.

"Because of the sensitive nature of Jackie's story, we decided to honor her request not to contact the man she claimed orchestrated the attack on her nor any of the men she claimed participated in the attack for fear of retaliation against her," managing editor Will Dana wrote in a statement.

Then Dana cited "discrepancies in Jackie's account."

Whether they meant to or not, Rolling Stone effectively told readers: Jackie lied about being raped. True, they couched it in the claim that they believed Jackie in the beginning. (Insert pat on the back here.)

But ultimately, Rolling Stone writes, "Our trust in her was misplaced."

Let's get something clear: Trusting Jackie wasn't the problem. Because false rape accusations are so rare, the decision to trust a person who says she was raped is never misplaced. If Rolling Stone had done its due diligence, it might have been able to defend its trust in its source when the fraternity pushed back on the accusation.

Instead, in the face of criticism, Rolling Stone is now implying that Jackie might have misled the reporter, rather than centering the blame squarely on its lack of journalistic standards. That's utterly irresponsible.

As a result, people may now read Rolling Stone's half-hearted apology and be dangerously skeptical of victims of sexual assault.

In fact, when survivors decide to come forward and report sexual assault, they are rarely lying. We don't know the details surrounding Jackie's specific case (Rolling Stone isn't talking), but jump to blame a victim — or imply that readers should be skeptical — and chances are you're wrong.

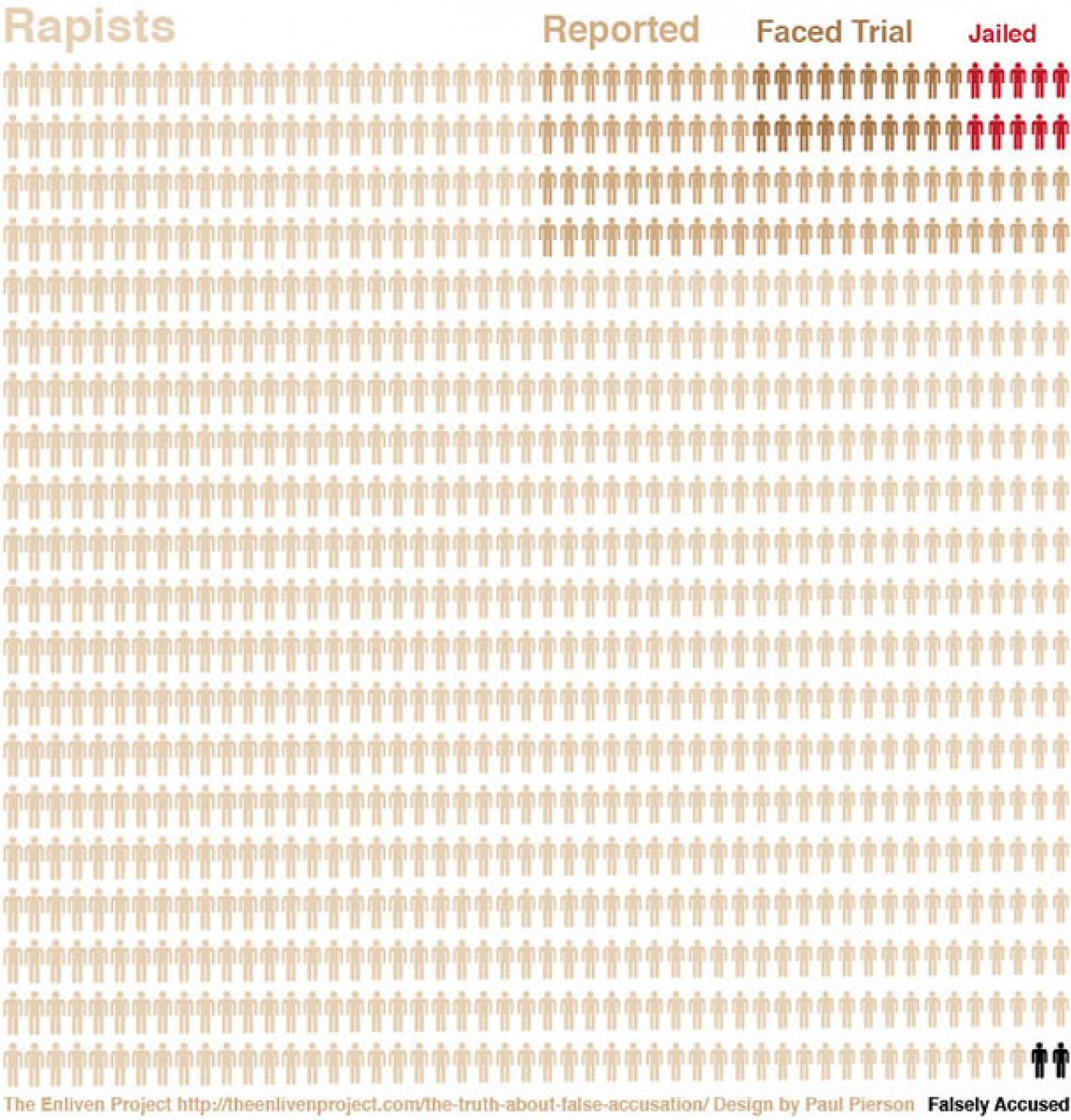

Out of all reported rapes and sexual assaults, only 2% to 10% are false reports, according to an analysis of several thorough studies. The most recent is a Northeastern study of 136 rape cases over a 10-year period. Only eight of those cases (5.9%) were coded as false allegations. In a 17-month period between January 2011 and May 2012 in England, there were 5,651 prosecutions for rape; of that number, 35 (0.6%) were prosecuted for making false accusations of rape, according to the Crown Prosecution Service.

The National Center for the Prosecution of Violence Against Women writes that what people view as the stereotypical signs of "real rape" are actually quite rare. According to prosecutors, "victims often omit, exaggerate or fabricate parts of their account, and they may even recant altogether. They are not typically hysterical when interviewed by medical professionals, law enforcement professionals, prosecutors or others."

That means many actual rape victims exhibit some of the stereotypical "red flag" behavior that an everyday person might find suspect. That does not mean they're lying.

Later on Friday, Rolling Stone's Dana tweeted that the magazine's failure in "getting the other side of the story" was "on us — not on her." But he did nothing to dispel the idea that Jackie was lying.

Critics of Rolling Stone's reporting maintain that insinuations about victims lying are likely to silence future victims. Not to mention that discrediting these women creates skepticism among the friends, family and administrations to whom they'll come for help.

"The girl who cried rape" is not a common person. At the very least, remember that when you're reviewing today's massive journalistic blunder.

http://mashable.com/2014/12/05/false-rape-accusations-rare/