We Lutherans do that, too. But more importantly, it does not require any particular faith or any faith at all to do the right thing. All it requires is love and empathy. At worst all it requires is recognition: they could be you in the same circumstances very easily.

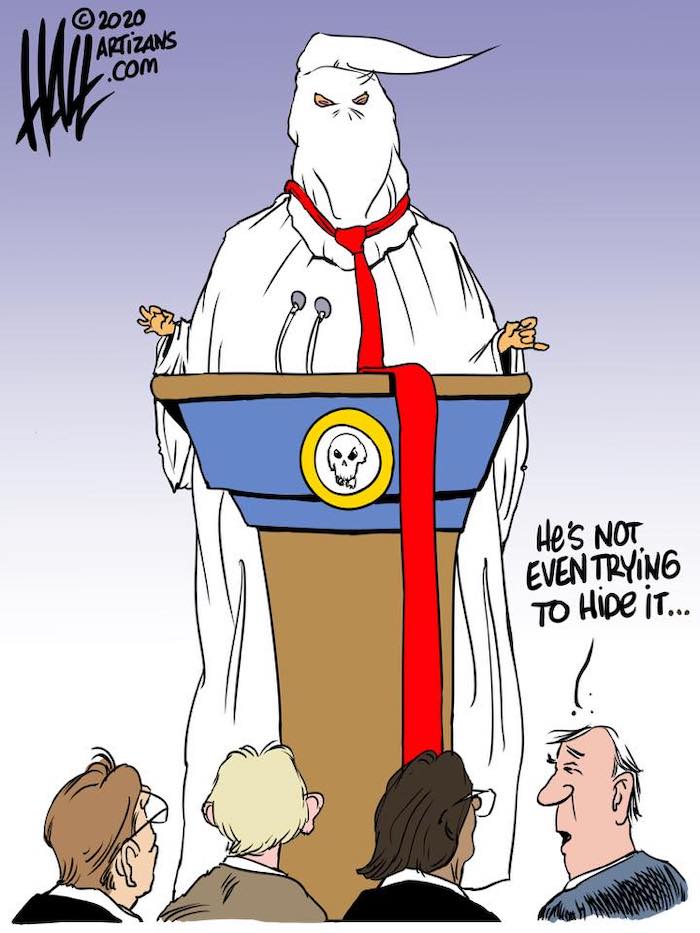

Top Trumps: the 10 worst things the former president said this year

Martin Pengelly

in Washington

Hard to keep track of all the racist, unhinged, authoritarian comments by the former president? Don’t worry, we’ve got you covered

In 2015, the man who coined Godwin’s law, a famous maxim about argument on the internet, wrote a column for the Washington Post. Its headline: “Sure, call Trump a Nazi. Just make sure you know what you’re talking about.”

By the lawyer and author Mike Godwin’s own definition, his law reads thus: “As an online discussion continues, the probability of a reference or comparison to Hitler or Nazis approaches one.” Since Republicans fell under Trump’s thrall, the law has often been invoked. Why? See our list of the 10 worst things Trump said in 2023:

Vermin

In November, in Claremont, New Hampshire, Trump continued his dominant primary campaign. His rant was familiar but it held something new:

We pledge to you that we will root out the communists, Marxists, fascists and the radical left thugs that live like vermin within the confines of our country.

Hillary Clinton, who Trump beat in 2016, had already likened him to Hitler. Ruth Ben-Ghiat, a historian from New York University, told the Washington Post: “Calling people ‘vermin’ was used effectively by Hitler and Mussolini to dehumanise people and encourage their followers to engage in violence.”

Poison

Of course, the signs were already there. In September, discussing immigration with the National Pulse, Trump said:

Nobody has ever seen anything like we’re witnessing right now … It’s poisoning the blood of our country.

He had already promised “the largest domestic deportation operation in American history”. Plans to hold migrants in camps would be reported. But Mehdi Hasan of MSNBC summed up the “poisoning” comment as “a straight-up white supremacist/neo-Nazi talking point”. Trump went there again in December, too.

Dictator

Trump wasn’t done. In December, at an Iowa town hall, the Fox News host Sean Hannity asked if he would promise not to “abuse power as retribution against anybody”. Trump said: “Except for day one”, then explained:

I love this guy. He says, ‘You’re not gonna be a dictator, are you?’ I say, ‘No, no, no – other than day one.’ We’re closing the border. And we’re drilling, drilling, drilling. After that I’m not a dictator, OK?

Noting Trump’s laughter and the crowd’s cheers, Philip Bump of the Washington Post wrote: “What fun! I guess we can put that to bed.”

Retribution

No one could say such comments were surprising. In March, closing CPAC in Maryland, Trump told conservatives:

In 2016, I declared: I am your voice. Today, I add: I am your warrior. I am your justice. And for those who have been wronged and betrayed: I am your retribution.

Jonathan Karl of ABC would report that the Trump strategist Steve Bannon said Trump was speaking in code, referring to a Confederate plot to take hostage – and eventually kill – President Abraham Lincoln.

Death

In September, the Atlantic profiled Mark Milley, then chair of the joint chiefs of staff. Milley’s work to contain Trump at the end of his presidency was already widely known but the profile set Trump off nonetheless. On Truth Social, referring to a call in which Milley assured Chinese officials he would guard against any attempted attack, Trump lamented …

… an act so egregious that, in times gone by, the punishment would have been DEATH!

Milley was moved to take “appropriate measures to ensure my safety and the safety of my family”.

Courts

This has been the year of the Trump indictment. He faces four, spawning 91 criminal charges regarding election subversion, retention of classified information and hush-money payments. On 4 August, lawyers for the federal special counsel Jack Smith notified a judge of a post in which Trump appeared to threaten them, writing:

If you go after me, I’m coming after you!

Trump claimed protected political speech but the exchange teed up one of many tussles over gag orders and the general impossibility of getting Trump to shut up.

Indict

A recurring question: if re-elected, will Trump seek to use the federal government against his enemies? The slightly garbled answer, as expressed to Univision in November, was of course … yes:

If I happen to be president and I see somebody who’s doing well and beating me very badly, I say go down and indict them, mostly they would be out of business. They’d be out. They’d be out of the election.

Animal

In April, Alvin Bragg, the Manhattan district attorney, filed 34 charges over Trump’s 2016 payments to Stormy Daniels, an adult film star who claims an affair. Trump had already made arguably racist comments about Letitia James, the New York attorney general. Aiming at Bragg, Trump used Truth Social to say:

He is a Soros-backed animal who just doesn’t care about right or wrong.

Calling Bragg an animal played to racism about Black people. “Soros-backed”, commonly used by Republicans, refers to the progressive financier George Soros and is widely regarded as antisemitic.

Whack job

In May, Trump was found liable for sexual abuse of the writer E Jean Caroll. Ordered to pay about $5m, he was not about to be quiet. The next night, in New Hampshire, he ranted:

And I swear and I’ve never done that … I have no idea who the hell – she’s a whack job.

Carroll called the comments “just stupid … just disgusting, vile, foul”. Then she sued Trump again.

All-out war

Trump is 77. Questions about his mental fitness for power are not going away. Recently, he has appeared to think he beat Barack Obama in 2016 and become confused about which Iowa city he was in. On 2 December, however, another Iowa gaffe seemed to point to a worrying truth:

That’s why it was one of the great presidencies, they say. Even the opponents sometimes say he did very well … but we’ve been waging an all-out war on American democracy.

There are bad years, and then there are years like 2023. Go ahead and admit it—was it one of the worst years of your life? Maybe even the worst year of all? You’re not alone. We’ve discussed reams of data and evidence recently showing just how badly the world’s faring, and people are doing—I call it the Modern Crisis of Being. Well-being’s plummeting, and that doesn’t mean “wellness,” but how our lives are actually doing.

2023 wasn’t just a bad year. We now live in times that history will regard as a turning point in the human story. Only we’re not turning in the right direction. Imagine a river, forking into two branches. We’re being carried along now by tides of rage, resentment, and regress—at the precise moment we should be making better, wiser choices. Is this what we human beings are limited to? Circles of folly, on an endless wheel of suffering? Are we capable of more? Such is the central question of this age, and realize, too, just how big, deep, and defining it is, cutting right to the root of us, paring us to the bone, revealing our truth in bitter detail.

Let’s put 2023 in perspective. Summer brought with it the arrival of climate change’s mega-scale impacts with a stunning, shocking fury. Times like these are so tumultuous that we scarcely now remember a few scant months ago. But temperatures shattered, on land, at sea, in the air. Megafires erupted. Crops failed. Droughts spread. And systems, too, began to crash—insurers pulled out of California, for example, one of the world’s richest regions, by a very long way. The sudden impact of climate change at these furious level worried scientists, and that’s an understatement. We appear to be at or near the zone where tipping points are hit, sending us into an unknown future, perhaps, of severe shock.

But that wasn’t how 2023 began—just a brief reminder of it’s midpoint. As the pandemic “receded”—not over, but banished, somehow from memory, speaking of it a taboo, everyone to play along with the myth that “Covid is over,” despite it still spreading this winter, hitting a peak of 1 in 3 people in America, for example—the idea was that…things would magically, instantly get better. That idea was a narrative shared by pundits, power figures, elites, who radiated a sunny optimism, having forced the myth of normalcy on us all yet again. Everything was going to be fine as 2023 dawned, they insisted.

And then the world fell into the jaws of a bitter, brutal “cost of living” crisis. In plainer English, just surviving became something bleak, getting harder by the day. The prices of basics surged and skyrocketed, from food to household goods. Meanwhile, incomes, of course, didn’t keep pace—welcome to life under predatory capitalism—but instead fell in real terms. People began to struggle, in unforeseen ways—not new in the human experience, to be sure, but new, perhaps, for them. American were stretched, for example, to the brink—by the autumn, a full 70% reported being “financially traumatized,” and the same percent lived paycheck to paycheck, the vast majority struggling just to pay the bills. Today, over half of Americans are “cashflow negative,” meaning: they’re broke.

Yet they’re the lucky ones. In our world, the mess we’ve made of it, the unlucky ones are, for example, the unfortunate souls selling organs to feed their kids, which is what Afghanis have resorted to under the Taliban.

The “cost of living” crisis was a body blow. A mega-shock, after a series of mega-shocks. The world didn’t go back to anything remotely resembling normal after the pandemic. Instead, now we seem to inhabit a shattered dystopia of broken societies, polities, and economies. Why is that?

The “cost of living” crisis went on to fuel yet another shock, the world’s sudden swerve towards the far right, its newfound embrace of demagogues and fanatics. Democracy had another bleak and crushing year, in over a decade of overwhelming losses for it. Even Europe’s mature social democracies, weighed down by stagnant economies, turned to their historical nemesis, in an eerie echo of history’s greatest mistakes. And in America? A grinning, jeering, sneering, screaming Donald Trump returned triumphantly to power.

There, the shock of the cost of living crisis was so acute that today, Trump bests Biden in the polls. Given the status quo, it’s hard to see how Trump won’t be elected. Yes, of course, the 14th Amendment should matter—we’ll save that discussion for future posts. For now, the point is the way that all these shocks intersected, multiplied, and fed one another.

You see, a curious thing is happening to our civilization now. It’s destabilizing and coming undone. There aren’t many examples of “runaway” dynamics in…anything. Usually, systems need energy, and produce diminishing returns. But self-accelerating dynamics are incredibly dangerous things, because they…propagate themselves. And this is the situation we face. The cost of living crisis accelerated the world’s shift to demagoguery, and the ongoing death of democracy. Meanwhile, the cost of living crisis was itself accelerated by climate change—economists won’t confirm it for another half decade or so, because the research takes time, and right about now, there isn’t much interest in it, but the skyrocketing prices of recent times are obviously driven by climate change, atop which what’s come to be called “greedflation” is piled.

Now we live in a profoundly different world. Think of how much has changed in one short decade. Economy: it’s gone from growth to stagflation. Our economies are nominally “growing,” but the average person’s fortunes are still diminishing, and that can only happen if and when the gains go to a tiny fraction at the very top. Politics: democracy’s gone from healthy to quite possibly facing extinction in our lifetimes, just 20% of the world fully democratic, declining at a rate of 5-10% a decade. Society: norms have been shattered, and rewritten, around cruelty, hostility, enmity, rage, stupidity, and the open contempt of truth, justice, equality, and freedom.

2023 was a turning point in all these ways. It was a terrible year for a reason. Not just one inflection point is being hit now—many are, all at once. Climate change is the obvious example. But far from the only one. Think about the economy: the age of stagflation we’re in now isn’t an anomaly, it’s the future, because we’re now out of easy sources of growth—in fact, we’re a civilization which doesn’t know how to make everything from food to raw materials to household goods without fossil fuels. Democracy, too, appears to have hit an inflection point, a deadly one, with European social democracy on the brink, and Americans openly embracing a man who flaunts being a “dictator” and speaks of the nation’s “blood” being “poisoned.”

So that’s why 2023 was such a terrible year. It was a series of inflection points, one after the other. To call them “shocks” even understates and obscures that point, because even a shock implies something temporary. None of these transformations appear to be temporary—take the example of Trump’s return: it tells that people haven’t come to their senses, after some kind of passing mania. Worse, these inflection points feed one another, politics destabilizing society destabilizing economics destabilizing climate and on and on, in a lethal circle of ruin, known as a doom loop.

History will look at us and say to itself, that was the era that they embraced a doom loop. Their civilization was on the brink, and it was evident in so many ways. And yet they chose not just to ignore it, but, in some kind of madness, turn towards it, strain their backs not against it, but for it.

I know how it sounds when I write stuff like this. But where else does the evidence leave me? Am I supposed to tell you everything’s rosy and fine? I’ve quoted you statistic after statistic, and I do it regularly. My job isn’t to be some kind of doomsayer—really. If the news was good, I’d happily tell you, and we’d discuss art, music, or books. My job is simply to help you make sense of the world. In times like these, the dominant narrative is badly wrong—and we all know it, because we feel it. We feel terrible about the world, ourselves, the future, where things are going, the collective human mind in a shockwave, afraid, anxious, uncertain—facts, not speculation, those feelings are exploding off the charts in historically significant ways now, and it’s for a reason. Nobody sane or thoughtful or wise thinks 2023 was a fantastic year—it was a terrible one, and we all feel it intensely, though we’re not supposed to talk about it. And yet all that itself is a clarion call. To wrest back what we can, while time still remains, of the beautiful and noble project called civilization. source

Biden administration again bypasses Congress for weapons sale to Israel

Antony Blinken tells Congress he made second emergency determination covering $147.5m sale for equipment

For the second time this month the Biden administration is bypassing Congress to approve an emergency weapons sale to Israel as Israel continues to prosecute its war against Hamas in Gaza under increasing international criticism.

The state department said on Friday that the secretary of state, Antony Blinken, had told Congress that he had made a second emergency determination covering a $147.5m sale for equipment, including fuses, chargers and primers, that is needed to make the 155mm shells that Israel has already purchased function.

“Given the urgency of Israel’s defensive needs, the secretary notified Congress that he had exercised his delegated authority to determine an emergency existed necessitating the immediate approval of the transfer,” the department said.

“The United States is committed to the security of Israel, and it is vital to US national interests to ensure Israel is able to defend itself against the threats it faces,” it said.

The emergency determination means the purchase will bypass the congressional review requirement for foreign military sales. Such determinations are rare, but not unprecedented, when administrations see an urgent need for weapons to be delivered without waiting for lawmakers’ approval.

Blinken made a similar decision on 9 December, to approve the sale to Israel of nearly 14,000 rounds of tank ammunition worth more than $106m.

Both moves have come as Joe Biden’s request for a nearly $106bn aid package for Ukraine, Israel and other national security needs remains stalled in Congress, caught up in a debate over US immigration policy and border security. Some Democratic lawmakers have spoken of making the proposed $14.3bn in American assistance to its Middle East ally contingent on concrete steps by the government of the Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, to reduce civilian casualties in Gaza during the war with Hamas.

The state department sought to counter potential criticism of the sale on human rights grounds by saying it was in constant touch with Israel to emphasize the importance of minimizing civilian casualties, which have soared since Israel began its response to the Hamas attacks in Israel on 7 October.

“We continue to strongly emphasize to the government of Israel that they must not only comply with international humanitarian law, but also take every feasible step to prevent harm to civilians,” it said.

“Hamas hides behind civilians and has embedded itself among the civilian population, but that does not lessen Israel’s responsibility and strategic imperative to distinguish between civilians and Hamas terrorists as it conducts its military operations,” the department said. “This type of campaign can only be won by protecting civilians.”

Bypassing Congress with emergency determinations for arms sales is an unusual step that has in the past met resistance from lawmakers, who normally have a period of time to weigh in on proposed weapons transfers and, in some cases, block them.

In May 2019, then secretary of state Mike Pompeo made an emergency determination for an $8.1bn sale of weapons to Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Jordan after it became clear that the Trump administration would have trouble overcoming lawmakers’ concerns about the Saudi and UAE-led war in Yemen.

Pompeo came under heavy criticism for the move, which some believed may have violated the law because many of the weapons involved had yet to be built and could not be delivered urgently. But he was cleared of any wrongdoing after an internal investigation.

At least four administrations have used the authority since 1979. President George HW Bush’s administration used it during the Gulf war to get arms quickly to Saudi Arabia.

When asked at a town hall on Wednesday to identify the cause of the United States Civil War, presidential candidate and former governor of South Carolina Nikki Haley answered that the cause “was basically how government was going to run, the freedoms, and what people could and couldn’t do…. I think it always comes down to the role of government and what the rights of the people are…. And I will always stand by the fact that, I think, government was intended to secure the rights and freedoms of the people.”

Haley has correctly been lambasted for her rewriting of history. The vice president of the Confederacy, Alexander Stephens of Georgia, was quite clear about the cause of the Civil War. Stephens explicitly rejected the idea embraced by U.S. politicians from the revolutionary period onward that human enslavement was “wrong in principle, socially, morally, and politically.” Instead, he declared: “Our new government is founded upon…the great truth, that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition.”

President Joe Biden put the cause of the Civil War even more succinctly: “It was about slavery.”

Haley has been backpedaling ever since—as well as suggesting that the question was somehow a “gotcha” question from a Democrat, as if it was a difficult question to answer—but her answer was not simply bad history or an unwillingness to offend potential voters, as some have suggested. It was the death knell of the Republican Party.

That party formed in the 1850s to stand against what was known as the Slave Power, a small group of elite enslavers who had come to dominate first the Democratic Party and then, through it, the presidency, Supreme Court, and Senate. When northern Democrats in the House of Representatives caved to pressure to allow enslavement into western lands from which it had been prohibited since 1820, northerners of all political stripes recognized that it was only a question of time until elite enslavers took over the West, joined with lawmakers from southern slave states, overwhelmed the northern free states in the House of Representatives, and made enslavement national.

So in 1854, after Congress passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act that allowed the spread of enslavement into previously protected western lands, northerners abandoned their old parties and came together first as “anti-Nebraska” coalitions and then, by 1856, as the Republican Party.

At first their only goal was to stop the Slave Power, but in 1859, Illinois lawyer Abraham Lincoln articulated an ideology for the new party. In contrast to southern Democrats, who insisted that a successful society required leaders to dominate workers and that the government must limit itself to defending those leaders because its only domestic role was the protection of property, Lincoln envisioned a new kind of government, based on a new economy.

Lincoln saw a society that moved forward thanks not to rich people, but to the innovation of men just starting out. Such men produced more than they and their families could consume, and their accumulated capital would employ shoemakers and storekeepers. Those businessmen, in turn, would support a few industrialists, who would begin the cycle again by hiring other men just starting out. Rather than remaining small and simply protecting property, Lincoln and his fellow Republicans argued, the government should clear the way for those at the bottom of the economy, making sure they had access to resources, education, and the internal improvements that would enable them to reach markets.

When the leaders of the Confederacy seceded to start their own nation based in their own hierarchical society, the Republicans in charge of the United States government were free to put their theory into practice. For a nominal fee, they sold farmers land that the government in the past would have sold to speculators; created state colleges, railroads, national money, and income taxes; and promoted immigration.

Finally, with the Civil War over and the Union restored on their terms, in 1865 they ended the institution of human enslavement except as punishment for crime (an important exception) and in 1868 they added the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution to make clear that the federal government had power to override state laws that enforced inequality among different Americans. In 1870 they created the Department of Justice to ensure that all American citizens enjoyed the equal protection of the laws.

In the years after the Civil War, the Republican vision of a harmony of economic interest among all Americans quickly swung toward the idea of protecting those at the top of society, with the argument that industrial leaders were the ones who created jobs for urban workers. Ever since, the party has alternated between Lincoln’s theory that the government must work for those at the bottom and the theory of the so-called robber barons, who echoed the elite enslavers’ idea that the government must protect the wealthy.

During the Progressive Era, Theodore Roosevelt reclaimed Lincoln’s philosophy and argued for a strong government to rein in the industrialists and financiers who dominated society; a half-century later, Dwight Eisenhower followed the lead of Democrat Franklin Delano Roosevelt and used the government to regulate business, provide a basic social safety net, promote infrastructure, and protect civil rights.

After each progressive president, the party swung toward protecting property. In the modern era the swing begun under Richard Nixon gained momentum with the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980. Since then the party has focused on deregulation, tax cuts, privatization, and taking power away from the federal government and turning it back over to the states, while maintaining that market forces, rather than government policies, should drive society.

But those ideas were not generally popular, so to win elections, the party welcomed white evangelical Christians into a coalition, promising them legislation that would restore traditional society, relegating women and people of color back to the subservience the law enforced before the 1950s. But it seems they never really intended for that party base to gain control.

The small-government idea was the party’s philosophy when Donald Trump came down the escalator in June 2015 to announce he was running for president, and his 2017 tax cuts for corporations and the wealthy indicated he would follow in that vein. But his presidency quickly turned the Republican base into a right-wing movement loyal to Trump himself, and he was both eager to get away from legal trouble and impeachments and determined to exact revenge on those who did not do his bidding. The power in the party shifted from those trying to protect wealthy Americans to Trump, who increasingly aligned with foreign autocrats.

That realignment has taken off since Trump left office in 2021 and his base wrested power from the party’s former leaders. Leaders in Trump’s right-wing movement have increasingly embraced the concept of “illiberal democracy” or “Christian democracy” as articulated by Russian autocrat Vladimir Putin or Hungary’s prime minister Viktor Orbán, who has demolished Hungary’s democracy and replaced it with a dictatorship. On the campaign trail lately, Trump has taken to echoing Putin and Orbán directly.

Those leaders insist that the equality at the heart of democracy destroys a nation by welcoming immigrants, which undermines national purity, and by treating women, minorities, and LGBTQ+ people as equal to white, heteronormative men. Their focus on what they call “traditional values” has won staunch supporters among the right-wing white evangelical community in the U.S.

Ironically, MAGA Republicans, whose name comes from Trump’s promise to “Make America Great Again,” want the United States of America, one of the world’s great superpowers, to sign onto the program of a landlocked country of fewer than 10 million people in central Europe.

MAGA’s determination to impose white Christian nationalism on the United States of America is a rejection of the ideology of the Republican Party in all its phases. Rather than either an active government that defends equal rights and opportunity or a small government that protects property and relies on market forces, which Republicans stood for as recently as eight years ago, today’s Republicans advocate a strong government that imposes religious rules on society.

They back strict abortion bans, book bans, and attacks on minorities and LGBTQ+ people. Last year, Florida governor Ron DeSantis directly used the state government to threaten Disney into complying with his anti-LGBTQ+ stance rather than reacting to popular support for LGBTQ+ rights. Missouri attorney general Andrew Bailey early this month used the government to go after political opposition, launching an investigation into Media Matters for America after the watchdog organization reported that the social media platform X was placing advertising next to antisemitic content. “I’m fighting to ensure progressive tyrants masquerading as news outlets cannot manipulate the marketplace in order to wipe out free speech,” Bailey said.

Domestically, the new ideology of MAGA means forcing the majority to live under the rules of a small minority; internationally, it means support for a global authoritarian movement. MAGA Republicans’ current refusal to fund Ukraine’s war against Russian aggression until the administration agrees to draconian immigration laws—which they are also refusing to participate in crafting—is not only a gift to Putin. It also suggests to any foreign government that U.S. foreign policy is changeable so long as a foreign government succeeds in influencing U.S. lawmakers. Under this system, American global leadership will no longer be viable.

When Nikki Haley said the cause of the Civil War “was how government was going to run, the freedoms, and what people could and couldn’t do,” she did more than avoid the word “slavery” to pander to MAGA Republicans who refuse to recognize the role of race in shaping our history. She rejected the long and once grand history of the Republican Party and announced its death to the world.

Why are ties between Russia and Israel ‘at lowest point since fall of the Soviet Union’?

Pjotr Sauer

Russia’s pro-Palestinian stance has inflamed tensions and underscored shift in relations since invasion of Ukraine

When Vladimir Putin spoke by telephone this month to Benjamin Netanyahu, their first conversation in weeks, the two leaders found themselves in an unusual dynamic, engaging not as partners but against the backdrop of historic tensions.

Once touting their friendly relationship – Netanyahu has used billboards showing himself next to Putin during election campaigning in Israel, even last year – the events of 7 October and Russia’s pro-Palestinian stance in the aftermath have brought a decisive schism in their ties.

“The two countries’ ties are absolutely at the lowest point since the fall of the Soviet Union,” said Nikolay Kozhanov, a former Russian diplomat in Tehran and now an associate professor at Qatar University.

The contrasting accounts released by Israel and Russia after the call on 10 December gave insight on the strained relationship, said Dr Vera Michlin-Shapir, of King’s College London and a former official at Israel’s national security council, who specialises in Russian foreign policy.

Netanyahu said in a statement he had spoken to Putin and voiced displeasure with “anti-Israel positions” taken by Moscow’s envoys at the UN, while voicing “robust disapproval” of Russia’s “dangerous” cooperation with its ally Iran.

The Kremlin, meanwhile, highlighted “the catastrophic humanitarian situation in the Gaza Strip”, with Putin saying Israel’s military response to the Hamas terror onslaught should not lead “to such dire consequences for the civilian population”.

“This was not a dialogue. This time around the two leaders just put forward their positions,” said Michlin-Shapir.

A day before their conversation, Moscow backed a UN resolution calling for an immediate ceasefire in the Gaza Strip and said the US was “complicit in Israel’s brutal massacre”, a not-so-subtle reference to the 21,000 people who Gaza health authorities say have been killed since the war began.

The ending of the complex entente between Russia and Israel underscored a larger global shift that had been under way in the Kremlin’s position on the Middle East since Putin launched his war in Ukraine, said Kozhanov. “Russia quickly realised that the ties with the west have been damaged for a long time,” he said.

After the start of the war, Kozhanov argued, Moscow started looking into ways to strengthen its economic and military ties with Arab states while also growing closer to Iran, which has been providing artillery shells, drones and missiles for Russia’s war efforts.

In a rare, one-day trip that underlined his warming relationship with key players in the Middle East, Putin earlier in December visited the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, where he received a grand welcome, despite his status in the west as a wanted man sought by the international criminal court for war crimes.

“Putin’s visit to the Middle East confirmed the empty noise in the words about the isolation of the Russian Federation,” Izvestia, a pro-Kremlin daily, triumphantly wrote after Putin’s trip.

Kozhanov said the Israel-Hamas war also provided Moscow with a rare opportunity to court the broader global south, which has accused the west’s rules-based order of hypocrisy over Palestinian deaths. In the process, the Kremlin was eager to claim the moral high ground, despite its own devastating record of human rights abuses during wars in Chechnya, Syria and, most recently, Ukraine.

“Putin’s Russia is very pragmatic,” said Kozhanov. “Moscow sensed that the events in Gaza are driving the global south away from the west and could make its attitudes more sympathetic to Moscow.”

For two decades under Putin, Russia and Israel pursued a delicate balance.

While the two countries often found themselves on opposite sides of the geopolitical spectrum, Israel sought contact with Russia in Syria and was careful not to antagonise Moscow, given its ties to Israel’s arch-rival, Iran.

Putin also courted the large Jewish population in Moscow and saw in Israel an ally in keeping the memory of the second world war alive, the monumental historical event around which the Russian leader has sought to build his presidency.

“It was never an alliance, but there was always a strategic understanding. Both countries needed each other,” said Michlin-Shapir.

But Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which made Putin a pariah in much of the west, placed Israel in a bind.

Many in Israel were left deeply uncomfortable with Russia’s framing of its invasion, with Moscow falsely comparing Ukraine’s government to Nazi Germany to justify its war, said Pinchas Goldschmidt, the former chief rabbi in Moscow.

In spring 2022, these tensions first spilled over into the public when Russian officials accused Israel of supporting the “neo-Nazi regime” in Kyiv. The spat was ignited after Russia’s foreign minister, Sergei Lavrov, recycled an antisemitic conspiracy theory claiming that Adolf Hitler “had Jewish blood” – comments that Israel described as “unforgivable and outrageous”.

“On 7 October, Israel woke up and found Russia on the opposite side of the war. But the foundations for the split were already laid when Putin invaded Ukraine,” said Michlin-Shapir.

Alexander Gabuev, the director of the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center, said it was only logical that Moscow opted to support the Iran-sponsored Hamas, as it was the option most beneficial for its war efforts in Ukraine.

The war in Ukraine has become “the raison d’être for the entire machinery of Putinism”, Gabuev wrote in a recent op-ed, pointing to Iran’s indispensable military support.

“This is why the Kremlin’s muted reaction to the 7 October terrorist attacks by Hamas and ensuing full-throated criticism of Israel’s war in Gaza would once have been unimaginable but is hardly surprising in 2023,” he said.

As the Hamas attack unfolded, Russian officials and state-controlled media quickly took up a pro-Palestinian position, cheering Israeli military and intelligence blunders, which were presented as a testament to western weakness.

The state rhetoric, which often had nods toward antisemitism, has partly been attributed to the anti-Jewish storming of an airport in the Russian region of Dagestan, during which a violent mob looked for Jewish passengers arriving from Israel.

The Israel-Hamas war has already proved to be a win for Putin by helping take the west’s focus off the war in Ukraine, with the US and the EU struggling to push through two critical aid packages that are deemed vital for Kyiv’s long-term survival.

“Russia now has an interest in prolonging this conflict in the Middle East,” said a senior European diplomat in Moscow, speaking on conditions of anonymity. He said he feared an all-out Israel-Hezbollah war would further derail any help for Ukraine.

The hard pro-Israeli position of the Ukrainian president, Volodymyr Zelenskiy, on the Gaza conflict, in which he sought to compare Hamas to Russia, has in the meantime alienated some of the countries in the global south. This, insiders say, could undo months of diplomatic efforts by the west and Ukraine to paint Moscow as a global pariah in the global south for breaching international law.

“It seemed a bit too easy and too fast for Zelenskiy to go full pro-Israel,” said a senior European official in Kyiv in November. Pointing to countries such as South Africa, Brazil, Indonesia and Turkey, the official said it could now be harder for Ukraine to make inroads after sustained diplomatic progress.

In an interview in Kyiv, Zelenskiy’s adviser Mykhailo Podolyak admitted there would be a “chill in relations” with non-western countries, but said once Ukraine would “be able to explain why this is happening and the role of Russia in it … we will be able to revive all our dialogues”.

For now, Ukraine appears to have little to show in return for supporting Israel. Before 7 October, Netanyahu had announced a nonaligned approach to the war in Ukraine, refusing to provide lethal weapons or much-desired air defence systems to Kyiv, an approach that is unlikely to change with the fighting in Gaza. Netanyahu has also reportedly rejected repeated requests by Zelenskiy to make a solidarity visit to Israel after the Hamas attack.

In contrast, Michlin-Shapir said the Hamas-Israeli war provided Putin with a new opportunity to impose himself on the global order.

The former Israeli official compared the current diplomatic efforts to Russia’s intervention in Syria in 2015, which brought Moscow back to the international table after it annexed Crimea a year before. “They managed to get out of isolation then. The Middle East always provides new opportunities for Russia,” she said.

Marc E. Elias@marceelias

1h

Trump won't accept the outcome of the election if he loses and

He is off the ballot.

He is on the ballot.

There is mail-in voting.

There is not mail-in voting.

Voting is easy.

Voting is hard.

The only way Trump will accept the outcome of the election is if he wins.

Speaking to Channel 12 news, the leader of the hard-right Religious Zionism party also doubled down on his refusal to transfer tax payments to the Palestinian Authority over concerns that the money will find its way to Gaza, sloughing off reported pressure from the United States on the matter and pushing back against insinuations that he and others had propped up Hamas as a convenient foil.

“We will be in security control, and we will need there to be civil [control],” Smotrich said. “I’m for completely changing the reality in Gaza, having a conversation about settlements in the Gaza Strip… We’ll need to rule there for a long time… If we want to be there militarily, we need to be there in a civilian fashion.”

The minister, who was arrested in 2005 while protesting Israel’s evacuation of its Gaza Strip settlements, also said Jerusalem could not allow Gaza to remain as a “hothouse of 2 million people who want destroy the State of Israel.”

“We want to encourage willful emigration, and we need to find countries willing to take them in,” he said.