A character assassination based on a ******* lie.

She has a name and everything.

did joe-haters create a robot girl to go on social media to tell what he did to her.

Former President Donald Trump on Saturday further escalated his immigration rhetoric and baselessly accused President Joe Biden of waging a “conspiracy to overthrow the United States of America” as he campaigned ahead of Super Tuesday’s primaries.

Trump has a long history of trying to turn attack lines back on his rivals in an attempt to diminish their impact. Biden has cast Trump as a threat to democracy, pointing to the former president’s efforts to overturn the results of the 2020 election. Those efforts culminated in the attack on the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, as his supporters tried to halt the peaceful transition of power.

Trump, who has responded by calling Biden “the real threat to democracy” and alleged without proof that Biden is responsible for the indictments he faces, turned to Biden’s border policies on Saturday, charging that “every day Joe Biden is giving aid and comfort to foreign enemies of the United States.”

“Biden’s conduct on our border is by any definition a conspiracy to overthrow the United States of America,” he went on to say in Greensboro, North Carolina. “Biden and his accomplices want to collapse the American system, nullify the will of the actual American voters and establish a new base of power that gives them control for generations.”

Similar arguments have long been made by people who allege Democrats are promoting illegal immigration to weaken the power of white voters — part of a racist conspiracy, once confined to the far right, claiming there is an intentional push by the U.S. liberal establishment to systematically diminish the influence of white people.

Trump leaned into the theory again at his rally later in Virginia, saying of the migrants: “They’re trying to sign them up to get them to vote in the next election.”

“Once again Trump is projecting in an attempt to distract the American people from the fact he killed the fairest and toughest border security bill in decades because he believed it would help his campaign. Sad,” Biden campaign spokesman Ammar Moussa said in a statement.

Trump’s campaign stops came three days before Super Tuesday, with elections in 16 states, including North Carolina and Virginia, where thousands of enthusiastic supporters gathered for an evening rally in downtown Richmond. The primaries will be the largest day of voting of the year ahead of November’s general election, which is shaping up as a likely rematch of 2020 between Trump and Biden.

Nikki Haley, Trump’s last major rival, also campaigned in North Carolina. Speaking to reporters after her event in Raleigh, about 80 miles away, the former U.N. ambassador demurred on her plans after Super Tuesday.

“We’re going to keep going and we’re going to keep pushing,” she said, arguing a majority of Americans don’t want either Biden or Trump as the nation’s leader.

Much of Trump’s speech in North Carolina focused on the slew of criminal charges he faces. While the former president has successfully harnessed his legal woes into a powerful rallying cry in the primaries, it is unclear how his message of grievance will resonate with the more moderate voters who will likely decide the general election.

“I stand before you today not only as your past and hopefully future president, but as a proud political dissident and a public enemy of a rogue regime,” Trump said, railing against what he called an “anti-Democratic machine.”

At both rallies, Trump played a recording of “Justice for All,” the version of the Star-Spangled Banner that he collaborated on with a group of defendants jailed over their alleged roles in the January 2021 insurrection, whom he refers to as “hostages.”

As he focuses on the general election, Trump has painted an apocalyptic vision of the country under Biden, particularly on the topic of immigration, which was the animating issue of his 2016 campaign and which he has once again seized on as the U.S. has experienced a record influx of migrants at the border.

Trump and Biden both visited the U.S.-Mexico border on Thursday to highlight their contrasting approaches to the issue.

On Saturday, Trump conjured images of Biden turning “public schools into migrant camps” and “the USA into a crime-ridden, disease-ridden dumping ground, which is what they’re doing.” He also spoke at length about the murder of Laken Riley, a 22-year-old nursing student whose alleged killer is a Venezuelan man who entered the U.S. illegally and was allowed to stay to pursue his immigration case.

Studies have found native-born U.S. residents are more likely to have been arrested for violent crimes than people in the country illegally, but Trump has seized on several high-profile incidents, including a recent video of a group of migrants brawling with police in Times Square.

“Not one more innocent American life should be lost to migrant crime,” Trump said.

Trump, who repeatedly attacks Biden’s intelligence and mental acuity, has been sensitive to questions of his own sharpness after he’s mixed up Haley with Nancy Pelosi and Biden with former President Barack Obama at past rallies.

Trump has lately sought to inoculate any questions by insisting he interchanges the names intentionally.

“I do that because you know that makes a point. Do we understand that, right? Because a lot of people say he’s running the country. I don’t personally think so,” Trump said early into his appearance in Virginia.

But more than an hour in to his free-flowing remarks, he seemed to mix up Obama and Biden again, when he said “Putin, you know, has so little respect for Obama that he’s starting to throw around the ‘nuclear’ word.”

Beyond their importance on Super Tuesday, North Carolina and Virginia are both states the Trump campaign is focused on for November.

Trump won North Carolina twice but watched his margin of victory shrink. Biden’s reelection campaign already has staff on the ground hoping to flip the state for the first time since 2008.

Virginia, meanwhile, had once been a swing state but for years has trended blue and Trump lost there twice. But a Trump campaign senior adviser told reporters Saturday that he believes “we could make Virginia competitive.”

In North Carolina, a festive atmosphere surrounded the Greensboro Coliseum Complex ahead of Trump’s rally. Supporters stood in a line that snaked through a web of metal barricades and extended hundreds of yards from the arena. License plates from North Carolina, Virginia and Tennessee filled the parking lot, where Trump flags flew alongside U.S. and Confederate flags on many vehicles.

“We just love Trump,” said, Mary Welborn, who lives in nearby Thomasville and expressed that she was frustrated by the criminal prosecutions and civil judgments against the former president. “The way he’s being treated is insane. No other president has been treated this way,” she said.

In Richmond, supporters started lining up Saturday morning for an evening rally at a downtown convention center. The entry lines stretched several blocks by mid-afternoon.

Ken Ballos, a retired police officer from nearby Hanover County who said he voted for Trump in 2016 and 2020, said he was eager at the prospect of a Trump-Biden rematch.

“Trump would eat him up,” Ballos said. source

One of the most remarkable developments of the new century has been the concentration of right-wing power and adulation in two men. Donald Trump is the obvious one, the unquestioned king of the American right. But easier to miss if you’re outside the MAGA world is the central importance of Elon Musk.

We’re familiar with Trump’s arc, of course. But why is Musk so important to the right? Why is a reported illicit drug user and unmarried father of 11 children by three women, a man whose social media site, X, is overrun with hatred and pornography, celebrated across the length and breadth of the new right, including parts of the Christian right?

The answer is that if Trump is MAGA’s champion, Musk is its gatekeeper. He doesn’t just use his immense reach (he has 174 million followers on X) to fight the left, he owns the right wing’s public square. This is because outside of X, the public isn’t reading the right. And as a result, X now shapes the right as much as even Fox News.

On Feb. 22, a website called The Righting released an analysis using Comscore data to compare web traffic at top right-wing sites from January 2020 to January 2024. The findings are surprising: Right-wing media appears to be struggling even more than mainstream media. Of the top right-wing sites in 2020, only Newsmax gained audience over the last four years. Every other right-wing site lost visitors, and most lost a staggering percentage of them.

For example, The Righting reports that The Washington Examiner lost 66 percent of its visitors. The Washington Times lost 82 percent. Breitbart lost 87 percent and The Daily Wire 73 percent. Aside from Newsmax and Fox News (which lost only 24 percent of its visitors) every other site has lost at least half its visitors in four years. Some have lost so many that The Righting could no longer measure their number of readers.

In fact, the loss is so profound that there are individual articles and columns in The New York Times that get more visitors than all of the content that many of these sites post for an entire month. As a practical matter this means that social media — and principally Musk’s X — becomes the central way in which many right-wing figures reach the public.

There are several consequences of this reality. It’s altering the way the right speaks. People will be naturally prone to focus most of their efforts on the medium through which they interact with the most people. The vast majority of people who interact with my work, for example, do so by reading my pieces, not by viewing my social media posts. My written work is the central focus of my professional life, while my social media posts are essentially an afterthought.

But what if that balance is reversed? It bends a person (or a movement) around the attitudes of social media and away from the kinds of argument that require the length of a column or essay. Social media doesn’t create a marketplace of ideas so much as a gallery of takes, where you can spend hours doomscrolling through short videos and snappy retorts.

That’s how a movement transfers its allegiance from the ideas of a man like William F. Buckley Jr. to an X “influencer” like @Catturd2 and his 2.4 million followers. It’s one reason a person like Tucker Carlson devolves from an interesting, idiosyncratic writer and thinker to an online shock jock and outrage merchant.

This transformation has the effect of further radicalizing the right. There’s a “Can you top this?” dynamic to posting that pushes people to extremes. In the offline world, paranoia is a liability. It inhibits you from seeing the world clearly. In parts of the online world, you’re considered a rube if you’re not paranoid, if you’re not seeing a leftist plot around every corner, if you’re not believing that Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce’s romance is a Biden administration psy-op that culminated with rigging the Super Bowl.

Moreover, a social media-centered movement understands what to think — the marching orders, however incoherent, typically trickle down from Trump — but often breaks down on the why. To take one vivid example, last week the Washington Post journalist Taylor Lorenz interviewed the founder of the popular X account Libs of TikTok, a woman named Chaya Raichik. Libs of TikTok is one of the most influential accounts in red America. Her posts don’t just trigger public outrage (and sometimes spawn an avalanche of threats against her targets), they directly affect legislation. Yet the interview is agonizing to watch. Time and again, Raichik proves unable or unwilling to articulate the basis for her beliefs. Her attitude is clear. Her ideas are not.

Finally, this dependence on social media is shaping the right’s position on free speech. As the platforms they created lose traffic, it becomes even more important that right-wing figures secure their place on the platforms they did not create. Thus, the same Republican Party that circled its wagons to protect corporate speech and the corporate exercise of religion in Supreme Court cases involving Citizens United, Hobby Lobby and 303 Creative has now passed laws in Florida and Texas trying to dictate private companies’ moderation policies.

To be clear: The dynamics of social media are corrosive to both right and left, and it’s not just right-wing sites that are losing readers. (The Righting also reported that CNN had lost 20 percent of its visitors, for example.) Left-wing activists on social media can be just as conspiratorial and vengeful as the worst actors on the right. But there’s been a substantial divergence. Whereas pre-Musk Twitter was once a center of the left-leaning journalistic and activist universes, they have substantially abandoned the site as a sideshow. For the right, meanwhile, Musk’s X has become the main stage.

It’s hard to think of a worse pair of human beings to shape the character of a movement than Donald Trump and Elon Musk. Yet here we are, with Trump controlling the right’s access to power, and Musk increasingly controlling the right’s access to the public. At best, those on the right who wish to maintain that access must cynically ignore, rationalize and minimize the two men’s profound flaws. At worst, it means actively embracing their personal values to curry favor. Like Trump’s ugly, erratic politics, Musk’s website is substantially contributing to the devolution of thinking on the right. The ideas are in retreat. It’s the attitude that matters now.

This week seems likely to be packed with news.

Today, Vice President Kamala Harris spoke about the crisis in the Middle East with strong words for both Hamas and Israel, calling for a ceasefire of at least six weeks, the return of hostages, and increased aid to the Palestinians. Such a deal is on the table. According to the U.S., Israel has agreed to it, and negotiators are waiting for a response from Hamas leaders.

Benny Gantz, a centrist officer in Israel’s war cabinet, is in Washington, D.C., where he will meet tomorrow with Vice President Harris and national security advisor Jake Sullivan, and on Tuesday with Secretary of State Antony Blinken. He did not have authorization from hard-right prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu for the visit. As growing numbers of Israelis are voicing dislike of Netanyahu, polls show that Gantz could command enough support to become prime minister if a new vote were held immediately.

This evening the U.S. Supreme Court indicated it will issue an opinion tomorrow. Marc Elias of Democracy Docket commented that it is “[v]ery likely the case involving Donald Trump's disqualification under Section 3 of the 14th Amendment.”

Also today, former South Carolina governor Nikki Haley won her first primary, winning 62.9% of the Republican vote in Washington, D.C. Trump won 33.2%. This victory makes Haley the first woman in history to win a Republican primary. It also illustrates that Trump’s support is terribly soft. Over the weekend, Haley picked up the endorsements of Senators Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) and Susan Collins (R-ME).

Headed into the week, Tuesday, March 5, is so-called Super Tuesday, when voters in fifteen states and one territory will vote for their choice for president. Those states are Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Vermont, and Virginia. In American Samoa, Democrats will vote on Tuesday, Republicans on Friday.

It seems likely that Super Tuesday will shift so many delegates into Trump’s column that he will have virtually locked up the Republican nomination.

But that timing poses a real problem for the Republican Party. Trump has to post a bond to cover the $83.3 million he owes writer E. Jean Carroll no later than Friday, March 8. His lawyers have been trying to get out of this requirement, asking for a “substantially reduced bond.” This suggests that he might have trouble covering the amount. And after he comes up with this sum, he still has the $454 million to pay in the civil fraud case against him in New York.

March 8 is also the day that Republican National Committee chair Ronna McDaniel steps down. The only people running to replace her are Trump loyalist Michael Whatley and Trump’s daughter-in-law Lara Trump, who hope to be co-chairs. Trump’s senior campaign adviser Chris LaCivita is running to be the RNC’s chief operating officer.

So Trump could clinch the nomination and control of the RNC just as it becomes crystal clear he has devastating financial and legal problems.

Also this week, far-right Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán is scheduled to meet with Trump at the Trump Organization’s property at Mar-a-Lago.

And Congress still must pass several appropriations bills. Meanwhile, House minority leader Hakeem Jeffries (D-NY) has suggested Democrats will protect House speaker Mike Johnson (R-LA) from a vote to oust him if he will bring up for a vote the national security supplemental bill that provides aid to Ukraine.

Thursday, President Biden will deliver the State of the Union address.

I’m already tired just thinking of it all, but this week might well provide some new clarity on a number of major issues.

On December 9, 2000, the SCOTUS received a request from the Bush campaign to halt the Florida recount. They granted that request the same day. Two days later (Dec 11)the SC heard oral arguments in Bush v Gore to effectively decide the outcome of the election. The next day - December 12, 2000 - finding that since no alternative vote counting method could be chosen before the “safe harbor” deadline in Title 3 of the U.S. Code - (December 12th) - rejected Gore’s request to extend the deadline and complete the recount. This effectively gave Bush the presidency. The SC took FOUR DAYS to decide that Bush would be president.

The SC that is presently sitting took over two weeks to announce that they would hear oral arguments regarding Trump’s claims that he should be immune from all prosecution. Then they set the hearing of oral arguments for another two months hence - “sometime in late April”.

I and much of the country believed the swiftness of the Bush v Gore decision was driven by the partisan corruption of Justice Scalia, and others.

If I say the delay before the immunity of Trump is decided on is clearly the result of the influence of partisan corruption on the SC, does everyone here agree that’s CLEARLY the case, or are there those here who will argue that it’s just being careful, constitutional, and such?

...does everyone here agree that’s CLEARLY the case...

Today the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that states cannot remove Donald Trump from the 2024 presidential ballot. Colorado officials, as well as officials from other states, had challenged Trump’s ability to run for the presidency, noting that the third section of the Fourteenth Amendment prohibits those who have engaged in insurrection after taking an oath to support the Constitution from holding office. The court concluded that the Fourteenth Amendment leaves the question of enforcing the Fourteenth Amendment up to Congress.

But the court didn’t stop there. It sidestepped the question of whether the events of January 6, 2021, were an insurrection, declining to reverse Colorado’s finding that Trump was an insurrectionist.

In those decisions, the court was unanimous.

But then five of the justices cast themselves off from the other four. Those five went on to “decide novel constitutional questions to insulate this Court and petitioner from future controversy,” as the three dissenting liberal judges put it. The five described what they believed could disqualify from office someone who had participated in an insurrection: a specific type of legislation.

Justices Elena Kagan, Sonia Sotomayor, and Ketanji Brown Jackson in one concurrence, and Justice Amy Coney Barrett in another, note that the majority went beyond what was necessary in this expansion of its decision. “By resolving these and other questions, the majority attempts to insulate all alleged insurrectionists from future challenges to their holding federal office,” Kagan, Sotomayor, and Jackson wrote. Seeming to criticize those three of her colleagues as much as the majority, Barrett wrote: “This is not the time to amplify disagreement with stridency…. [W]ritings on the Court should turn the national temperature down, not up.”

Conservative judge J. Michael Luttig wrote that “in the course of unnecessarily deciding all of these questions when they were not even presented by the case, the five-Justice majority effectively decided not only that the former president will never be subject to disqualification, but that no person who ever engages in an insurrection against the Constitution of the United States in the future will be disqualified under the Fourteenth Amendment’s Disqualification Clause.”

Justice Clarence Thomas, whose wife, Ginni, participated in the attempt to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election, notably did not recuse himself from participating in the case.

There is, perhaps, a larger story behind the majority’s musings on future congressional actions. Its decision to go beyond what was required to decide a specific question and suggest the boundaries of future legislation pushed it from judicial review into the realm of lawmaking.

For years now, Republicans, especially Republican senators who have turned the previously rarely-used filibuster into a common tool, have stopped Congress from making laws and have instead thrown decision-making to the courts.

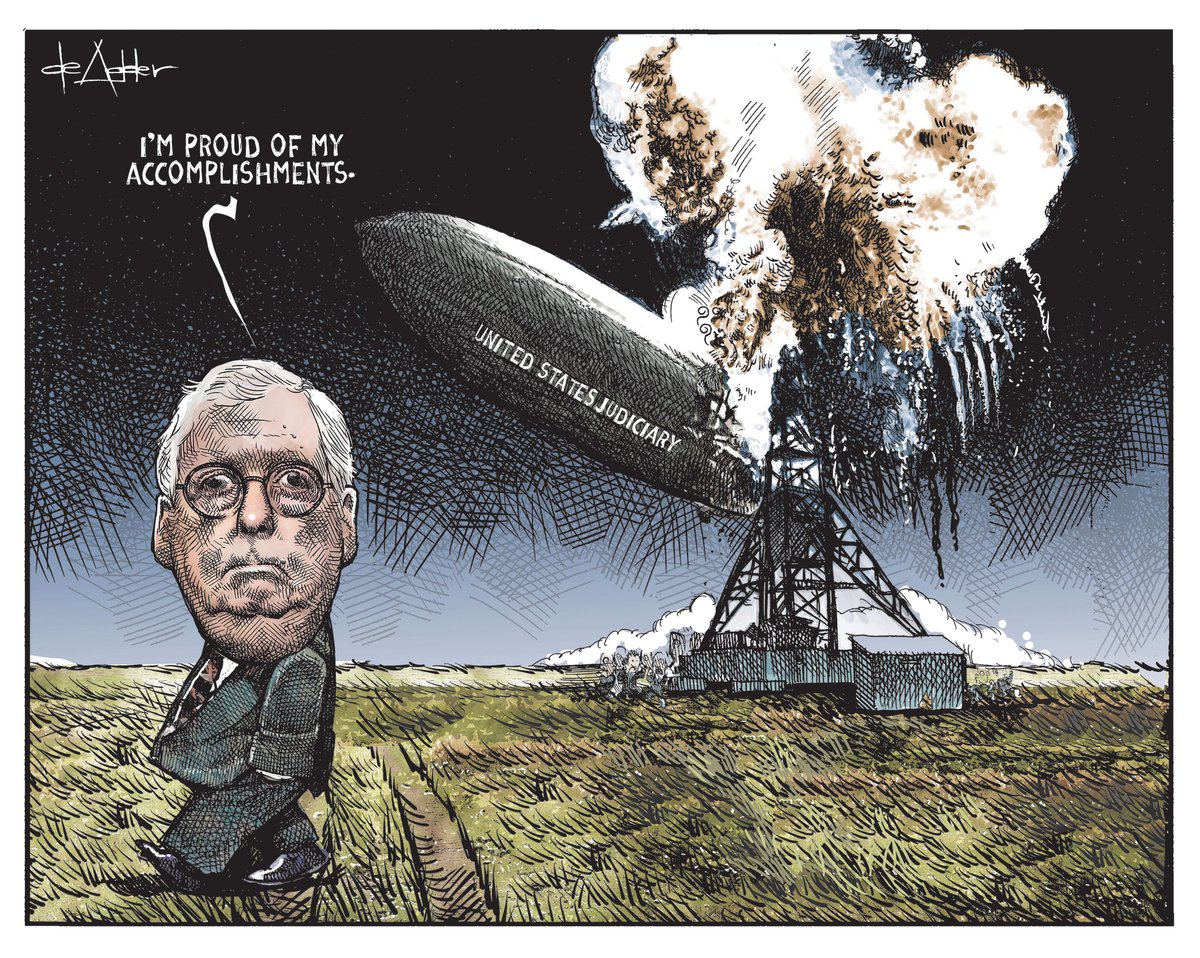

Two days ago, in Slate, legal analyst Mark Joseph Stern noted that when Mitch McConnell (R-KY) was Senate majority leader, he “realized you don’t need to win elections to enact Republican policy. You don’t need to change hearts and minds. You don’t need to push ballot initiatives or win over the views of the people. All you have to do is stack the courts. You only need 51 votes in the Senate to stack the courts with far-right partisan activists…[a]nd they will enact Republican policies under the guise of judicial review, policies that could never pass through the democratic process. And those policies will be bulletproof, because they will be called ‘law.’”

By now, you’ve heard. The Supreme Court ruled for Trump—unanimously, no less. Let’s cut to the Post’s excellent summary, and then get to the meat of the matter.

WaPo: “The Supreme Court on Monday unanimously sided with Donald Trump, allowing the former president to remain on the election ballot and reversing a Colorado ruling that disqualified him from returning to office because of his conduct around the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol.

The justices said the Constitution does not permit a single state to disqualify a presidential candidate from national office, declaring that such responsibility “rests with Congress and not the states.” The court warned of disruption and chaos if a candidate for nationwide office could be declared ineligible in some states, but not others, based on the same conduct.

“Nothing in the Constitution requires that we endure such chaos — arriving at any time or different times, up to and perhaps beyond the inauguration,” the court said in an unsigned, 13-page opinion.”

What really happened here? Here’s the opinion itself.

Here are my six takeaways.

1. The Supreme Court evaded the question—and abrogated its key responsibility, too—by leaving democracy no remedy for insurrection.

Is someone who broke their oath of office and led an insurrection disqualified or not? According to the Supreme Court, States can’t make that decision—only Congress can.

Never mind the obvious hypocrisy of “chaos” breaking loose if a candidate were disqualified—versus that of precisely the same candidate openly promising to install a dictatorship. Which is worse? Never mind, too, the rank hypocrisy of “states rights’” for some issues, but none for this much more fundamental and central one. Which counts now?

2. America’s now in a constitutional no-mans’ land, a crisis.

There’ll be the kind of person who says “let’s decide this at the ballot box! It shouldn’t be decided judicially.” They’re wrong, not as a matter of opinion, but as an institutional matter. If States aren’t.

How precisely is Congress to enforce Section 3 of the 14th Amendment, which is what all this hinges on? Remember, Section 3 says, explicitly, someone who violates this, attempts a coup, is disqualified. It doesn’t mince words. So what’s the Court’s actual remedy to all this?

In their decision, the Court says: “Shortly after ratification of the Amendment, Con- gress enacted the Enforcement Act of 1870. That Act authorized federal district attorneys to bring civil actions in federal court to remove anyone holding nonlegislative of- fice—federal or state—in violation of Section 3, and made holding or attempting to hold office in violation of Section 3 a federal crime.”

So in other words, the Supreme Court is saying that Congress decides this issue legislatively—it’s a federal crime to violate Section 3.

But there’s a big problem with that.

Even that doesn’t disqualify a person from running for office. As we all know by now, even if Trump’s convicted in his insurrection case, he’s still probably allowed to run for President again, and assume the office—and worse, this judgment only confirms all that. But that’s precisely what Section 3 says, extremely clearly, and we’ll come to that in a second.

In other words, the Court’s remedy isn’t actually a remedy. Violate Section 3, maybe you’ll go to jail, but the problem—can you hold office again?—isn’t remedied at all, in the slightest. And in this sense, of course, justice isn’t done, which is the point, wait for it, of a judiciary. (And no, “jail time” isn’t a remedy in question, we’re not just talking “punishment,” but “remedy,” as in, solving the problem, remedying the wound to democracy itself.) If you can still be President from jail…we all know that the remedy doesn’t actually matter and isn’t one.

So who can actually disqualify someone who’s violated Section 3 of the 14th Amendment from holding office? According to the Supreme Court, nobody can. States can’t. The Supreme Court can’t. And Congress can’t either—beyond legislation, what exactly is it to do? That’s it’s role in government institutionally, after all. Is it to issue a Special Edict? Assume Special Powers? What does that even mean?

So if you ask me, the Supreme Court has failed, and failed badly. I’m not even on the side saying that Trump should be automatically disqualified, as a matter of political opinion. But I am saying the Supreme Court has said nobody can disqualify anyone else from holding office. It has effectively said that there is no institution which can enforce Section 3 at all.

Not States, explicitly, not some kind of referendum, only Congress, but wait, even being convicted of precisely that federal crime doesn’t disqualify someone from office. So where does that leave us?

In an institutional Twilight Zone. In a Kafkaesque maze. A nowhere-land. If no institution of governance can act to make Section 3 real, does it exist at all? And this is precisely the outcome that authoritarians tend to want—vagueness, a cloudiness, a lack of clarity, so that the rules can always be bent to their will.

What’s the Point of a Judiciary?

Section 3 couldn’t be more explicit.

“No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State leg- islature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.”

See how clear that is? Does the constitution matter, or not, or only sometimes?

That leaves us with one possibility, that Congress could maybe enforce Section 3 through a vote. But what kind of vote?

If the only way that Section 3 can be enforced is through, let’s say, a Congressional vote, then of course, that’s the weakest guardrail against authoritarianism imaginable, because in such a situation—insurrection, coup, overthrow—presumably, there’s a pretty good chance such a vote would be tainted to begin with. “Votes” of such kinds aren’t laws or rules, and what constitutions are supposed to give are laws and rules—permanent lines, not temporary, shifting ones.

Section 3 is interestingly explicit about what it’d take to “remove the disability” of disqualification—a 2/3 vote of each house. But even more interestingly, it’s not explicit about what it’d take to disqualify someone in the first place. That’s a pretty good tell that the only enforcement mechanism of this amendment wasn’t just meant to be Congress, because of course, if it was, then presumably, it’d just stated so as clearly for disqualification as it does and did for disqualification. That’s a bit abstruse, but I think you see my point.

Imagine now the opposite. What if Congress, reading this ruling, sighs, and decides—we all know it won’t, so just imagine—that a 2/3rds vote can disqualify a candidate, like a Trump? Of course, then said candidate could just challenge it, appeal to the Supreme Court, who, given this reading of affairs, would just as likely say: nowhere does the constitution give Congress the power to do that.

So however we read this ruling, the Supreme Court is saying: nobody can be disqualified for office, by any institution, in practice, full stop. That’s an incredibly foolish and dangerous thing for a Supreme Court to say, and we’ll come to why. First, though…

Constitutionally, Section 3 is as clear as it gets. Someone who breaks their oath and engages in insurrection is disqualified.

The Supreme Court has said: maybe, maybe not. It’s not up to us to say. It’s up to Congress to say. But nowhere does it say such a thing in the constitution itself, which of course shreds the notion of “originalism” so beloved of the fanatics on the court. We can’t answer that question, says this Supreme Court. Maybe it’s Congress, maybe it’s the Department of Justice, maybe it’s someone at the federal level. But who? How, precisely? In what way? And why isn’t it the judiciary?

3. In this way, the Court’s ducked the central question: why isn’t it the judiciary’s job to disqualify candidates? Is that how democracies should—and indeed, do—work?

The Supreme Court have laid out plenty of options. It could have established criteria for what an insurrection is, what the bar for disqualification is, and asked States to present evidences that rises to that level. It could have specified a number of ways to enforce Section 3, or at least a number of possibilities, and sent the issue back to Congress, or the Department of Justice. It didn’t do any of the above. Instead, it basically said, and this is takeaway number three, and I guess it’s the big one…

4. The Supreme Court didn’t just say “Trump’s qualified.” It went much further, and said effectively said that nobody can be disqualified from office, by any institution of governance, no matter how grave their abuses of power are.

What is a Well-Designed Democracy?

Let’s examine a bit further what the Supreme Court’s really saying here. Who should decide whether or not a candidate’s qualified for office? That’s a primary function of a democracy. The Supreme Court’s saying that judiciaries shouldn’t decide that question, and that legislative bodies should, like Parliaments or Congresses.

That’s a poor answer in democracy’s own terms, too, given what we know about democracy. In a well-designed democracy? It’s exactly the judiciary who should decide who’s qualified for executive office or not. Not Congress or Parliament. Why? Precisely because Congresses and Parliaments are governed by parties, but judiciaries are, at least nominally, not explicitly politically aligned. When we say that “Congresses and Parliaments should decide who’s fit to be in the executive branch,” the conflict of interest, when you think about for the merest moment, couldn’t be clearer: all kinds of problems of party politics quickly emerge. That’s why in most well-designed democracies, it’s never Congresses and Parliaments who decide on the executive branch, and if they do, it’s a position less important than head of state.

So to say “the judiciary shouldn’t decide this matter” is an incredibly foolish stance to take. It’s exactly the job of a judiciary to check the fitness of both executive and legislative branches, decide on qualification and disqualification, because, well, who else is going to do it? Asking executive and legislature to merely check one another is simply asking for trouble and dysfunction.

“Banana republic” politics is badly misunderstood by a lot of Americans. In “Banana republics,” the last bulwark and semblance of democratic rule comes down to the judiciary. Precisely because there, badly designed democracies mean that executive and legislature, working hand in hand, unable to check one another, end up in bed together instead, and proceed to loot the country.

5. America’s Supreme Court’s not exactly a set of the sharpest tools in the shed—but for it to be this ignorant about what a well-designed democracy is, and how one works…where judiciaries can and do decide fitness-for-office issues, not legislatures…that’s breathtaking.

Again, I’m not saying Trump should be disqualified. But I am saying that a society which can’t answer that question—in which nobody can be disqualified from office, and their abuses and crimes simply don’t matter anymore…that kind of society is already ceasing to be a democracy. Because of course a democracy is founded on the rule of law, for which constitutions lay foundations, and assign powers to branches of government.

But when a judiciary decides that a constitution’s amendments, clauses, powers don’t matter—that no institution can enforce them, then it’s saying: they’re simply theoretical. They don’t exist in reality. As matters of actual governance, versus some kind of numinous philosophy, they can’t be acted upon. In this case, by saying only the legislative branch can check the executive branch—and the judiciary can’t and shouldn’t—but wait, the legislative branch can’t do that in practice, America’s Supreme Court is saying that all this is just academic anyways.

And in that sense, such a judiciary is also saying that democracy doesn’t matter, because then neither do constitutions. If a judiciary can’t decide on what the powers of a branch of government are, how is a democracy to function? If it simply says that a power clearly delineated in a constitution doesn’t exist in practice, then what sort of slippery slope are we on, exactly?

I’d be happier if the Supreme Court had at least given us something to debate, discuss, chew on. Don’t want to disqualify Trump—sure, don’t—let’s get real, this court was made for him by him. But this is the worst outcome of all. Section 3 doesn’t matter, and the 14th Amendment is nice in theory, but in practice, hey—sorry, doesn’t really exist.

Is that still democracy? I don’t know, but it’s at the very least an extremely slippery slope.

6. This is one of the final nails in American democracy’s coffin, if you ask me.

Trump v Anderson is a case that’ll define history. It’ll be remembered, if I had to bet, as the moment that sealed America’s fate, which looks, if the election were held today, and any day in the last few months, increasingly like a Trump Dictatorship.

This Supreme Court will be remembered as the worst sort of judiciary—not just the kinds that enables authoritarians, which are penny-ante, but as the sort who turns their backs on the sacred principles that bind us together in this project called civilization. That constitutions are documents of consent, which join people together in unions, and violating them is a grave offense precisely because it offends us all, history, futurity, the present, democracy itself. For none of that to matter is quite something.

I know those are harsh words, so reconsider again, that I’ve never been emphatically on the side of disqualifying Trump. But to see the answer to that question becoming: we won’t disqualify him, in fact, we’ll just ignore the ideas of constitutuonality, law, and consent, and say that nobody can be disqualified for anything, period, nah, nah, nah, here we are, thumbing our nose in your face like babies.

It’s childish. This level of illogic? This absolute? Even kids would probably do a better job of doing their jobs. It makes no sense, though, because making sense in this case doesn’t matter, and thumbing their noses at the rest of us, at history, at the world, at democracy is what does

This judgment? It’s a clear a statement you could have about what contempt really is. For…everything but raw power, asserted to the point of violence. The Justices aren’t just nailing democracy’s coffin shut. They’re kicking them in, with scorn. There’s the sense of a sneer in all this, for even asking the question, and in return, an angry scowl, here’s how little your precious democracy matters, and then a grin: see what we did? Now nobody can do what you asked.

We took away that power entirely, the very one you wanted. From everyone. Poof, gone. Nah, nah, nah. Thumb-face. Suck on this, losers. You wanted it decided? We decided. Not yes or no. We went much further than that. By saying that it doesn’t really exist and never did.

So all this, my friends? This is a terrible way for democracy to die. In disgrace, pitilessly, bereft—abandoned, in the end, even by those were to be its very guardians to the last.

As of Monday, March 4, 2024, Section 3 of the 14th Amendment of the Constitution is essentially a dead letter, at least as it applies to candidates for federal office. Under the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling that reversed the Colorado Supreme Court’s decision striking Donald Trump from the state’s primary ballot, even insurrectionists who’ve violated their previous oath of office can hold federal office, unless and until Congress passes specific legislation to enforce Section 3.

In the aftermath of the oral argument last month, legal observers knew with near-certainty that the Supreme Court was unlikely to apply Section 3 to Trump. None of the justices seemed willing to uphold the Colorado court’s ruling, and only Justice Sonia Sotomayor gave any meaningful indication that she might dissent. The only real question remaining was the reasoning for the court’s decision. Would the ruling be broad or narrow?

A narrow ruling for Trump might have held, for example, that Colorado didn’t provide him with enough due process when it determined that Section 3 applied. Or the court could have held that Trump, as president, was not an “officer of the United States” within the meaning of the section. Such a ruling would have kept Trump on the ballot, but it would also have kept Section 3 viable to block insurrectionists from the House or Senate and from all other federal offices.

A somewhat broader ruling might have held that Trump did not engage in insurrection or rebellion or provide aid and comfort to the enemies of the Constitution. Such a ruling would have sharply limited Section 3 to apply almost exclusively to Civil War-style conflicts, an outcome at odds with the text and original public meaning of the section. It’s worth noting that, by not taking this path, the court did not exonerate Trump from participating in an insurrection.

But instead of any of these options, the court went with arguably the broadest reasoning available: that Section 3 isn’t self-executing, and thus has no force or effect in the absence of congressional action. This argument is rooted in Section 5 of the amendment, which states that “Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.”

But Section 5, on its face, does not give Congress exclusive power to enforce the amendment. As Justices Elena Kagan, Sotomayor and Ketanji Brown Jackson pointed out in their own separate concurring opinion, “All the Reconstruction amendments (including the due process and equal protection guarantees and prohibition of slavery) ‘are self-executing,’ meaning that they do not depend on legislation.” While Congress may pass legislation to help enforce the 14th Amendment, it is not required to do so, and the 14th Amendment still binds federal, state and local governments even if Congress refuses to act.

But now Section 3 is different from other sections of the amendment. It requires federal legislation to enforce its terms, at least as applied to candidates for federal office. Through inaction alone, Congress can effectively erase part of the 14th Amendment.

It’s extremely difficult to square this ruling with the text of Section 3. The language is clearly mandatory. The first words are “No person shall be” a member of Congress or a state or federal officer if that person has engaged in insurrection or rebellion or provided aid or comfort to the enemies of the Constitution. The Section then says, “But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each house, remove such disability.”

In other words, the Constitution imposes the disability, and only a supermajority of Congress can remove it. But under the Supreme Court’s reasoning, the meaning is inverted: The Constitution merely allows Congress to impose the disability, and if Congress chooses not to enact legislation enforcing the section, then the disability does not exist. The Supreme Court has effectively replaced a very high bar for allowing insurrectionists into federal office — a supermajority vote by Congress — with the lowest bar imaginable: congressional inaction.

As Kagan, Sotomayor and Jackson point out, this approach is also inconsistent with the constitutional approach to other qualifications for the presidency. We can bar individuals from holding office who are under the age limit or who don’t meet the relevant citizenship requirement without congressional enforcement legislation. We can enforce the two-term presidential term limit without congressional enforcement legislation. Section 3 now stands apart not only from the rest of the 14th Amendment, but also from the other constitutional requirements for the presidency.

In one important respect, the court’s ruling on Monday is worse and more consequential than the Senate’s decision to acquit Trump after his Jan. 6 impeachment trial in 2021. Impeachment is entirely a political process, and the actions of one Senate have no bearing on the actions of future Senates. But a Supreme Court ruling has immense precedential power. The court’s decision is now the law.

It would be clearly preferable if Congress were to pass enforcement legislation that established explicit procedures for resolving disputes under Section 3, including setting the burden of proof and creating timetables and deadlines for filing challenges and hearing appeals. Establishing a uniform process is better than living with a patchwork of state proceedings. But the fact that Congress has not acted should not effectively erase the words from the constitutional page. Chaotic enforcement of the Constitution may be suboptimal. But it’s far better than not enforcing the Constitution at all.

They kinda did, but they’re still right about not letting states decide on disqualifying candidates?

Sharp comments on this topic from Kagan and Kavanaugh were consistent with the court’s overall unease – as made clear by their questioning – with the possibility that different states might settle this question of national importance by following a dizzying array of varying procedures. source

It looks like Colorado will lose. An argument which seemed to get support on both sides was that other states would react by accusing opposing candidates of crimes and kicking them off the ballot. Which makes me wonder how political gerrymandering is considered a state matter and states can pretty much do what they like – with certain restrictions – but engaging in or promoting "insurrection", which is explicitly mentioned in the Constitution as making a candidate ineligible, can be finessed this way.