Abstract

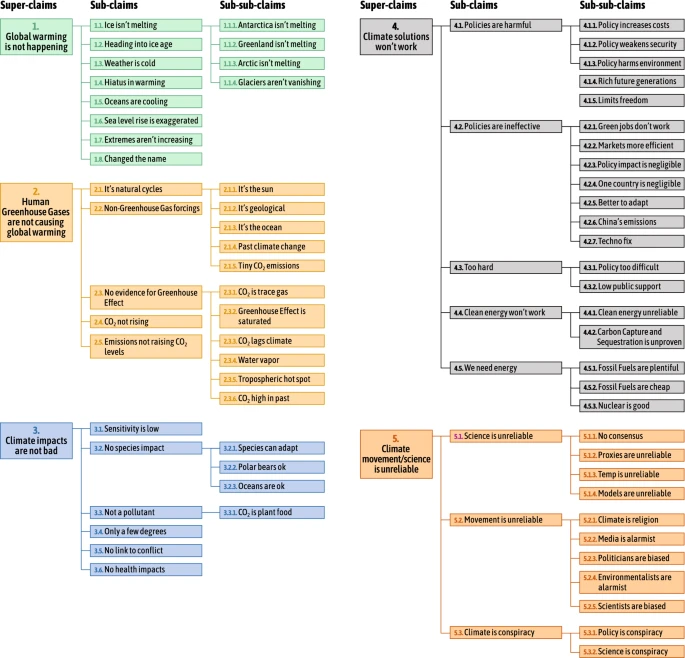

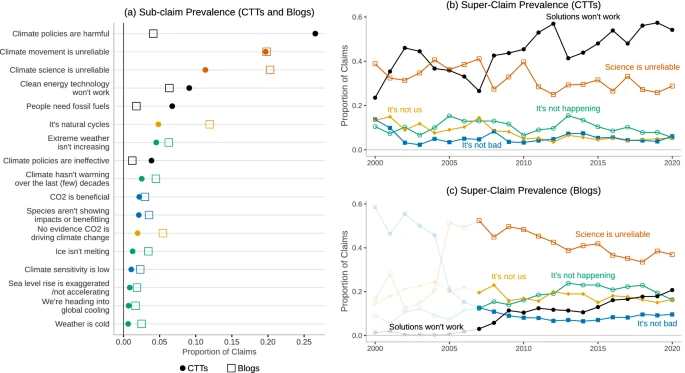

A growing body of scholarship investigates the role of misinformation in shaping the debate on climate change. Our research builds on and extends this literature by (1) developing and validating a comprehensive taxonomy of climate contrarianism, (2) conducting the largest content analysis to date on contrarian claims, (3) developing a computational model to accurately classify specific claims, and (4) drawing on an extensive corpus from conservative think-tank (CTTs) websites and contrarian blogs to construct a detailed history of claims over the past 20 years. Our study finds that the claims utilized by CTTs and contrarian blogs have focused on attacking the integrity of climate science and scientists and, increasingly, has challenged climate policy and renewable energy. We further demonstrate the utility of our approach by exploring the influence of corporate and foundation funding on the production and dissemination of specific contrarian claims.

Introduction

Organized climate change contrarianism has played a significant role in the spread of misinformation and the delay of meaningful action to mitigate climate change1. Research suggests that climate misinformation leads to a number of negative outcomes such as reduced climate literacy2, public polarization3, canceling out accurate information4, reinforcing climate silence5, and influencing how scientists engage with the public6. While experimental research offers valuable insight into effective interventions for countering misinformation3,7,8, researchers increasingly recognize that interdisciplinary approaches are required to develop practical solutions at a scale commensurate with the size of online misinformation efforts9. These solutions not only require the ability to categorize relevant contrarian claims at a level of specificity suitable for debunking, but also to achieve these objectives at a scale consistent with the realities of the modern information environment.

An emerging interdisciplinary literature examines the detection and categorization of climate misinformation, with the vast majority relying on manual content analysis. Studies have focused on claims associated with challenges to mainstream positions on climate science (i.e., trend, attribution, and impact contrarianism)10,11, doubt about mitigation policies and technologies12,13, and outright attacks on the reliability of climate science and scientists14,15. Researchers, moreover, have examined the prevalence of contrarian claims in conservative think tank (CTT) communications14,16, congressional testimonies17,18, fossil fuel industry communications19, and legacy and social media20,21. Given the significant costs associated with manual approaches for content analysis, several recent studies have explored computational methods for examining climate misinformation, ranging from applications of unsupervised machine learning methods to measure climate themes in conservative think-tank articles15,22, to supervised learning of media frames such as economic costs of mitigation policy, free market ideology, and uncertainty23.

Our work builds on and extends existing computational approaches by developing a model to detect specific contrarian claims, as opposed to broad topics or themes. We develop a comprehensive taxonomy of contrarian claims that is sufficiently detailed to assist in monitoring and counteracting climate contrarianism. We then conduct the largest content analysis of contrarian claims to date on CTTs and blogs—two key cogs in the so-called climate change “denial machine”24—and employ these data to train a state-of-the-art deep learning model to classify specific contrarian claims (Methods). Next, we construct a detailed history of climate change contrarianism over the past two decades, based on a corpus of 255,449 documents from 20 prominent CTTs and 33 central contrarian blogs. Lastly, we demonstrate the utility of our computational approach by observing the extent to which funding from “dark money”25, the fossil fuel industry, and other conservative donors correlates with the use of particular claims against climate science and policy by CTTs.

Here's another reminder of the precarious position that the world's climate and ecosystems are in: a new study estimates that global warming could push the Antarctic ice sheet past a tipping point in as little as 10 years.

In other words, the point of no return in terms of ice sheet loss is arriving earlier than previously thought, and we may well already be in the midst of it. That could have serious consequences when it comes to sea level rise globally, and the local habitats that animals in Antarctica rely on.

To get a better idea of what's happening right now, the researchers went back into the past, looking at the continent's history over the last 20,000 years – back to the last ice age – through ice cores extracted from the sea floor.

"Our study reveals that during times in the past when the ice sheet retreated, the periods of rapid mass loss 'switched on' very abruptly, within only a decade or two," says paleoclimatologist Zoë Thomas, from the University of New South Wales in Australia.

"Interestingly, after the ice sheet continued to retreat for several hundred years, it 'switched off' again, also only taking a couple of decades."

As icebergs break off Antarctica, they float down a major channel known as Iceberg Alley. Debris released from these icebergs accumulates on the seafloor, giving researchers a record of history some 3.5 kilometers (2.2 miles) under the water.

By combining this natural logbook of iceberg drift with computer models of ice sheet behavior, the team was able to identify eight phases of ice sheet retreat across recent millennia. In each case, the ice sheet destabilization and subsequent restabilization happened within a decade or so.

The results published by the researchers augment modern satellite imagery, which only goes back around 40 years: they show increasing losses of ice from the interior of the Antarctic ice sheet, not just changes in ice shelves already freely floating on the water.

"We found that iceberg calving events on multi-year time scales were synchronous with discharge of grounded ice from the Antarctic ice sheet," says glaciologist Nick Golledge, from the Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand.

The study showed the same sea rise pattern happening in each of the eight phases too, with global sea levels affected for several centuries and up to a millennium in some cases. Further statistical analysis identified the tipping points for these changes.

If the current shift in ice in Antarctica can be interpreted in the same way as the past events identified by the researchers, we might already be in the midst of a new tipping point – something we've seen in other parts of the world and the Arctic in recent years.

"If it just takes one decade to tip a system like this, that's actually quite scary because if the Antarctic Ice Sheet behaves in future like it did in the past, we must be experiencing the tipping right now", Thomas says.

Further evidence for these tipping points can be found in cores previously analyzed from the region, the researchers report, and the latest study also matches up with earlier models of ice sheet loss from the region.

"Our findings are consistent with a growing body of evidence suggesting the acceleration of Antarctic ice mass loss in recent decades may mark the beginning of a self-sustaining and irreversible period of ice sheet retreat and substantial global sea level rise," says geophysicist Michael Weber, from the University of Bonn in Germany.

The research has been published in Nature Communications.

Looters targeting Bay Area businesses struck again Sunday evening, with smash-and-grab thieves hitting a mall in Hayward, California and taking merchandise from a Lululemon store in San Jose, CBS San Francisco reports.

It was the third day in a row that large mobs of robbers went after retailers in the region.

Hayward police told CBS San Francisco they responded around 5:30 p.m. Sunday to multiple calls from stores in Southland Mall.

Witnesses said a large mob caused a huge disturbance inside the mall, with some briefly taking over a jewelry store.

Witnesses described some 40 to 50 looters wielding hammers and other tools looting Sam's Jewelers, breaking glass cases and quickly fleeing. The Macy's store was also ransacked.

In video taken during the robbery, workers can be heard inside Sam's Jewelers screaming in fear.

"(There was) a whole bunch of glass shattering," said one person who was at the mall during the incident.

Witnesses said it was actually the tail end of a much scarier and bigger scene.

"I would say at least 30 to 40 [people] from what I saw," said another witness. "But then after the main group of kids rushed out, we saw 15 to 20 scattering, and some even came back in."

CBS San Francisco spoke with two women who work near Sam's Jewelers. They and other mall workers said some kids ran into other stores and left with shoes and clothing.

"We saw all the other stores closing. They were panicking, so we were panicking and quickly closed our store and barricaded ourselves," said one of the women.

"It was very scary," said one mall worker. "People with no morals, no sense for other people's safety. I feel helpless. It's disturbing."

Police couldn't immediately say how much jewelry was taken or how much merchandise other stores in the mall lost.

It was unclear if the Hayward robbery was connected to the one targeting a Louis Vuitton store among other businesses in San Francisco's Union Square on Friday or the Nordstrom ransacking and robbery in Walnut Creek on Saturday. Thieves also hit up multiple marijuana dispensaries in Oakland.

Meanwhile in San Jose Sunday evening, police said a group of suspects entered the Lululemon store in Santana Row at about 6:30 and took merchandise. They fled prior to police arriving. No other information was immediately available.

"It was insane"

On Saturday night, dozens of looters swarmed into the Nordstrom store in downtown Walnut Creek, terrorizing shoppers, assaulting employees, ripping off bag loads of merchandise and ransacking shelves before fleeing in a several vehicles waiting for them on the street.

Walnut Creek Lt. Ryan Hibbs told CBS San Francisco three people were in custody and others were being sought.

"Walnut Creek police investigators are in the process of reviewing surveillance footage to attempt to identify other suspects responsible for this brazen act," authorities said Sunday.

Police began receiving calls from Nordstrom employees about the looting at around 9 p.m. Hibbs said there were approximately 80 people who ran into the store and began looting and smashing shelves.

Two employees suffered injuries when they were assaulted and another was pepper sprayed by the suspects.

Brett Barrette, a manager of the P.F. Chang's restaurant across from the Nordstrom store, watched as the bedlam unfolded.

"I probably saw 50-80 people in like ski masks with crowbars, a bunch of weapons," he said. "They were looting the Nordstrom."

"There was a mob of people," he continued. "The police were flying in. It was like a scene out of a movie. It was insane."

Many numbers are swirling around the climate negotiations at the United Nations climate summit in Glasgow, CoP26. These include global warming targets of 1.5 degrees Celsius and 2.0℃, recent warming of 1.1℃, remaining carbon dioxide budget of 400 billion tonnes, or current atmospheric CO2 of 415 parts per million.

It’s often hard to grasp the significance of these numbers. But the study of ancient climates can give us an appreciation of their scale compared to what has occurred naturally in the past. Our knowledge of ancient climate change also allows scientists to calibrate their models and therefore improve predictions of what the future may hold.

Recent work, summarised in the latest report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), has allowed scientists to refine their understanding and measurement of past climate changes. These changes are recorded in rocky outcrops, sediments from the ocean floor and lakes, in polar ice sheets, and in other shorter-term archives such as tree rings and corals. As scientists discover more of these archives and get better at using them, we have become increasingly able to compare recent and future climate change with what has happened in the past, and to provide important context to the numbers involved in climate negotiations.

For instance one headline finding in the IPCC report was that global temperature (currently 1.1℃ above a pre-industrial baseline) is higher than at any time in at least the past 120,000 or so years. That’s because the last warm period between ice ages peaked about 125,000 years ago – in contrast to today, warmth at that time was driven not by CO2, but by changes in Earth’s orbit and spin axis. Another finding regards the rate of current warming, which is faster than at any time in the past 2,000 years – and probably much longer.

But it is not only past temperature that can be reconstructed from the geological record. For instance, tiny gas bubbles trapped in Antarctic ice can record atmospheric CO2 concentrations back to 800,000 years ago. Beyond that, scientists can turn to microscopic fossils preserved in seabed sediments. These properties (such as the types of elements that make up the fossil shells) are related to how much CO2 was in the ocean when the fossilised organisms were alive, which itself is related to how much was in the atmosphere. As we get better at using these “proxies” for atmospheric CO2, recent work has shown that the current atmospheric CO2 concentration of around 415 parts per million (compared to 280 ppm prior to industrialisation in the early 1800s), is greater than at any time in at least the past 2 million years.

Other climate variables can also be compared to past changes. These include the greenhouse gases methane and nitrous oxide (now greater than at any time in at least 800,000 years), late summer Arctic sea ice area (smaller than at any time in at least the past 1,000 years), glacier retreat (unprecedented in at least 2,000 years) sea level (rising faster than at any point in at least 3,000 years), and ocean acidity (unusually acidic compared to the past 2 million years).

In addition, changes predicted by climate models can be compared to the past. For instance an “intermediate” amount of emissions will likely lead to global warming of between 2.3°C and 4.6°C by the year 2300, which is similar to the mid-Pliocene warm period of about 3.2 million years ago. Extremely high emissions would lead to warming of somewhere between 6.6°C and 14.1°C, which just overlaps with the warmest period since the demise of the dinosaurs — the “Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum” kicked off by massive volcanic eruptions about 55 million years ago. As such, humanity is currently on the path to compressing millions of years of temperature change into just a couple of centuries.

Distant past can help predict the near future

For the first time in an IPCC report, the latest report uses ancient time periods to refine projections of climate change. In previous IPCC reports, future projections have been produced simply by averaging results from all climate models, and using their spread as a measure of uncertainty. But for this new report, temperature and rainfall and sea level projections relied more heavily on those models that did the best job of simulating known climate changes.

Part of this process was based on each individual model’s “climate sensitivity” — the amount it warms when atmospheric CO2 is doubled. The “correct” value (and uncertainty range) of sensitivity is known from a number of different lines of evidence, one of which comes from certain times in the ancient past when global temperature changes were driven by natural changes in CO2, caused for example by volcanic eruptions or change in the amount of carbon removed from the atmosphere as rocks are eroded away. Combining estimates of ancient CO2 and temperature therefore allows scientists to estimate the “correct” value of climate sensitivity, and so refine their future projections by relying more heavily on those models with more accurate climate sensitivities.

Overall, past climates show us that cs. Unless emissions are reduced rapidly and dramatically, global warming will reach a level that has not been seen for millions of years. Let’s hope those attending COP26 are listening to messages from the past.

Much of the millions of metric tons of plastic waste that washes into the sea each year is broken down into tiny fragments by the forces of the ocean, and researchers are beginning to piece together what this means for organisms that consume them. Scientists in Korea have turned their attention toward the top of the food chain by exploring the threat these particles pose to mammal brains, where they were found to act as toxic substances.

In recent years, studies have revealed the kind of threat microplastics pose to marine creatures. This has included weakening the adhesive abilities of muscles, impairing the cognitive ability of hermit crabs and causing aneurysms and reproductive changes in fish. They've turned up in the guts of sea turtles all over the world, and been discovered in seal poo as evidence of them traveling up the food chain. Research has also shown they can alter the shape of human lung cells.

To further our understanding of these dangers, researchers at Daegu Gyeongbuk Institute of Science and Technology orally administered polystyrene microplastics two micrometers in size or smaller to mice over the course of seven days. Like humans, mice have a blood-brain barrier that prevents most foreign substances, and especially solids, from entering the organ, but the scientists found that the microplastics were able to make their way through.

Once in the brain, the scientists found that the particles built up in the microglial cells, which are key to healthy maintenance of the central nervous system, and this had a significant impact on their ability to proliferate. This was because the microglial cells saw the plastic particles as threat, causing changes in their morphology and ultimately leading to apoptosis, or programmed cell death.

Additionally, the scientists carried out experiments on human microglial cells and also observed changes in their morphology, along with changes to the immune system via alterations to the expression of relevant genes, related antibodies and microRNAs. As seen in the mouse brains, this also induced signs of apoptosis.

“The study shows that microplastics, especially microplastics with the size of 2 micrometers or less, start to be deposited in the brain even after short-term ingestion within seven days, resulting in apoptosis, and alterations in immune responses, and inflammatory responses," says study author Dr. Seong-Kyoon Choi." Based on the findings of this research, we plan to conduct additional research that can further reveal the brain accumulation of microplastics and the mechanism of neurotoxicity."

Do not eat deer advisory issued for greater Fairfield area

Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife, in conjunction with the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Maine CDC), has detected high levels of PFAS in some deer harvested in the greater Fairfield area and is issuing a do not eat advisory for deer harvested in the area.

This area encompasses multiple farm fields that have been contaminated by high levels of PFAS through the spreading of municipal and/or industrial sludge for fertilizer that contained PFAS. Deer feeding in these contaminated areas have ingested these chemicals, and now have PFAS in their organs and meat. Click here to view a map of the do not eat advisory area.

Poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) have been used for decades in a variety of household and consumer products, including non-stick cookware, carpet, waterproof clothing, and food packaging products such as pizza boxes and microwave popcorn bags. PFAS were also used in firefighting foams. Known as “forever chemicals” since they do not break down, PFAS persist in the environment and are transferred into soil, water, plants, and animals.

Hunters who have already harvested a deer in the area are advised not to eat the deer, and to dispose of the deer in their trash or landfill. The department will offer those who harvested a deer in the advisory area an opportunity to take an additional deer in the 2022 hunting season. Hunters should call the department at 207-287-8000 or email [email protected] for more information.

If you have questions about health effects from PFAS or blood testing, please contact the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) at 866-292-3474 (toll-free in Maine) or 207-287-4311.

By the late 21st century, northeastern U.S. cities will see worsening hurricane outcomes, with storms arriving more quickly but slowing down once they've made landfall. As storms linger longer over the East Coast, they will cause greater damage along the heavily populated corridor, according to a new study.

In the new study, climate scientist Andra Garner at Rowan University analyzed more than 35,000 computer-simulated storms. To assess likely storm outcomes in the future, Garner and her collaborators compared where storms formed, how fast they moved and where they ended from the pre-industrial period through the end of the 21st century.

The researchers found that future East Coast hurricanes will likely cause greater damage than storms of the past. The research predicted that a greater number of future hurricanes will form near the East Coast, and those storms will reach the Northeast corridor more quickly. The simulated storms slow to a crawl as they approach the East Coast, allowing them to produce more wind, rain, floods, and related damage in the Northeast region. The longest-lived tropical storms are predicted to be twice as long as storms today.

The study was published in Earth's Future, which publishes interdisciplinary research on the past, present and future of our planet and its inhabitants.

The changes in storm speed will be driven by changes in atmospheric patterns over the Atlantic, prompted by warmer air temperatures. While Garner and her colleagues note that more research remains to be done to fully understand the relationship between a warming climate and changing storm tracks, they noted that potential northward shifts in the region where Northern and Southern Hemisphere trade winds meet or slowing environmental wind speeds could be to blame.

"When you think of a hurricane moving along the East Coast, there are larger scale wind patterns that generally help push them back out to sea," Garner said. "We see those winds slowing down over time." Without those winds, the hurricanes can overstay their welcome on the coast.

Garner, whose previous work focused on the devastating East Coast effects of storms like Hurricane Sandy, particularly in the Mid-Atlantic, said the concern raised by the new study is that more storms capable of producing damage levels similar to Sandy are likely.

And the longer storms linger, the worse they can be, she said.

"Think of Hurricane Harvey in 2017 sitting over Texas, and Hurricane Dorian in 2019 over the Bahamas," she said. "That prolonged exposure can worsen the impacts."

From 2010 to 2020, U.S. coastlines were hit by 19 tropical cyclones that qualified as billion-dollar disasters, generating approximately $480 billion in damages, adjusted for inflation. If storms sit over coasts for longer stretches, that economic damage is likely to increase as well. For the authors, that provides clear economic motivation to stem rising greenhouse gas emissions.

"The work produced yet more evidence of a dire need to cut emissions of greenhouse gasses now to stop the climate warming," Garner said.

Co-author Benjamin Horton, who specializes in sea-level rise and leads the Earth Observatory of Singapore at Nanyang Technological University, said, "This study suggests that climate change will play a long-term role in increasing the strength of storms along the east coast of the United States and elsewhere. Planning for how to mitigate the impact of major storms must take this into account."

Last spring, the Financial Times published a useful series of charts showing the correlation between CO2 emissions and the global distribution of wealth. The inequalities of the climate crisis are often, in many ways rightly, conceptualized as inequities between countries — particularly those of a few rich, carbon-intensive, industrialized economies and the rest.

But, as the FT’s data very clearly showed, there’s actually a stark and highly visible divide between a tiny minority of extremely wealthy people and everyone else. Taken as a whole, those in the global top 1 percent of income account for 15 percent of emissions, which is more than double the share of those in the bottom half. The extremely wealthy have only gotten richer over the past thirty years and, as the data shows, their carbon footprints have gotten much bigger as well.

When this perspective is narrowed to individual countries, the class divide vis-à-vis carbon emissions is truly astonishing to behold. In the United States, those in the top decile of income alone account for half of household emissions while the bottom half account for under 10 percent. While America is admittedly a pretty extreme case, the same basic pattern holds true across many large industrialized economies — a point which underscores that the divides within countries are often at least as important as the divides between them.

There’s a periodic genre of environmental writing which argues that the road to a greener future runs through a kind of radical collective penance. If we really want to save the planet, or so this line of thinking goes, we all need to give up things like uninterrupted electricity use. Yet the fact remains that the well-off, and especially the extremely wealthy, are far more responsible for climate change than the people who cut their lawns, serve them food, or produce the goods they buy and consume. As the Financial Times’ Stefan Wagstyl quite succinctly put it: “Almost everything the wealthy do involves higher emissions, from living in bigger houses to running larger cars and flying more often, especially by private jet. Eating meat comes into it, as does owning a swimming pool. Not to mention a holiday home. Or homes.”

source

It may well be the case that fighting climate change will require middle-class and even working-class people in wealthy countries to change their lifestyles in the decades ahead. Given, however, the extent to which the rich are disproportionately responsible for global emissions, and the widespread public consensus around raising their taxes, it would be both politically popular and sound policy-wise to emphasize redistributive solutions to the climate crisis.

The rich, in effect, need to be made much less rich if we’re going to reduce global emissions — and, if we want to fight climate change, taxing their wealth is both a moral and an environmental imperative.

t was our “last chance to act”, according to Sheldon Whitehouse of the Democratic Party. The “last best hope for the world”, according to John Kerry. Boris Johnson invoked James Bond doomsday machines, declared it “one minute to midnight”, and warned that “If we don’t act now it will be too late.” “Make or break”, said Grenada’s minister for Climate and Environment.

Naturally, it broke.

Prior to Glasgow, the UN set three major criteria for the success of COP26:

• Obtain commitments to cut CO2 emissions in half by 2030;

• Commit $100 billion annually in financial aid from rich nations to poor ones (a pledge already made back in 2015 at the Paris meeting but never honored because, you know, who gives a ****); and

• Ensure that half of that money goes to helping the developing world adapt to climate change.

By the time festivities concluded over the weekend, not a single one of these objectives had been met. Not a single ******* one. By the UN’s own criteria, COP26—our “last chance to act”—was a failure.

Not that you’ll catch any of the suits behind the mics admitting as much. What you’ll hear is endless defensive wankery about “progress”. What a miraculous breakthrough, that for the first time a COP document actually mentions fossil fuels! (Even though it doesn’t call for phasing them out. Hell, it doesn’t even call for an end to subsidies.) Isn’t it wonderful, how all these countries have pledged to end net deforestation by 2030! (A nonbinding pledge, mind you, not unlike another made back in 2014 which somehow didn’t stop deforestation from increasing by another 40%. Really, the fact that Jair Bolsonaro felt comfortable signing the damn thing tells you all you need to know.) Isn’t it great that we’re going to be kicking the can down the road in one-year increments now, instead of the five years we were doing before? And Kudos to this side deal that the US and China have cut to, well, do something. About emissions. Sometime.

Even Elizabeth May—of Canada’s Green Party—put on her Pollyanna hat and danced a desperate little jig, reminiscing about how unthinkable it would have been, even ten ago, to see India make any commitment at all to fighting climate change—as if that somehow excuses India’s role in deleting the “phase out fossil fuels” provision. As if the the geosphere might now prick up its rocky little ears and and say Well, I was going to plunge the planet into a post-apocalyptic hellscape, but now that India admits there’s a problem I guess I’ll just change the heat capacity of the atmosphere and give everyone a few more decades. As though the bar we had to clear was what some short-sighted political sleazebag in India was willing to do ten years ago, and not what the laws of physics are doing to us right now.

Not that May doesn’t have a lot of company, here in the aftermath. John Kerry—he of the “last best hope for the world”—is singing a different tune tune now that said hope is gone. “It’s a good deal for the world,” he says now. “Can’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good.” But that’s not what’s happening, of course. We’re not letting the perfect be the enemy of the good; we’re letting scientific necessity be the enemy of the politically palatable.

So nobody’s talking about “success” any more. How can they, when we’re still on track for 2.4°C even if every country at COP26 honors all its shiny new commitments? Progress is the new buzzword. The COPpers have promised to nudge the Titanic a few more degrees to the left; keep it up and we’ll have changed course enough to avoid the iceberg entirely in just another hour or two.

Too bad we’re going to hit the ******* thing in thirty seconds.

So what now? Our “last chance” has come and gone. Is there anything at all we can do now, except wring our hands and clutch our pearls and continue to pump out first-world babies with megalodon-sized carbon bootie-prints?

George Monbiot gives it the ol’ college try over at The Guardian, cites a couple of papers about social tipping points and the power of the grass roots. Sharpe and Lenton talk hopefully about domino effects and the way incremental advances in technology can cascade into massive changes on national scales (the explosive growth of the electric car market in Norway is their go-to example). Centola et al describe an interesting social experiment showing that views held by as little as 21% of a population can ultimately tip over and become mainstream. But Sharpe and Lenton have to admit that their cascade effects frequently rely on policy changes made by the same governments who just screwed the pooch at COP26; nor do they address the countervailing impact of government policies designed to thwart constructive phase shifts (for example, the way Texas penalized people who installed solar panels by charging them for “infrastructure costs” to support the fossil grid they were opting out of). And Centola et al’s study is interesting as far as it goes, but the opinions it flips are innocuous things like “what would you call this picture”. It doesn’t explore the flexibility of opinions rooted in fear or brainstem prejudice, nor does it consider scenarios where powerful top-down rulers actively promote certain narratives and suppress others.

Monbiot makes a valiant effort, but he doesn’t convince me.

Anyone familiar with my own recent work might anticipate my own blue-sky solution: rewire Human Nature. Save Humanity by turning it into something else; hell, think of how much less destructive we’d be as a species if we just figured out how to short-circuit hyperbolic discounting. But that’s scifi speculation, that’s a solution to implement—at best— sometime in the future, if the tech ever catches up to my fever dreams. It doesn’t help us now.

If you’re looking for something that might help us out of the current crisis, maybe all you need to do is look at how the various delegates reacted to the failure of COP26.

Boris Johnson, who was all one-minute-to-midnight at the start of proceedings, called it “a historic success” afterward. John “last best hope” Kerry opined “”It’s got a few problems, but it’s all in all a very good deal.” For all their previous dire rhetoric, they act as if they’re pretty much okay with the outcome.

You know who isn’t okay? Aminath Shaunam, from the Maldives: “This deal does not bring hope to our hearts. It will be too late for the Maldives”. The prime minister of Barbados: “Two degrees is a death sentence.” The foreign minister of Tuvalu, which could be underwater by century’s end; he filmed a speech standing knee-deep in the ocean to make a point.

Those who feel personally threatened by this crisis want desperately to take all necessary measures. The John Kerrys and Boris Johnsons of the world? They’re rich. They’re first-world. They’re insulated: they’ll probably make out okay even under the worst-case scenario. So why should they care? Oh, they’ll walk the walk if they have to—but when the chips are down they’ll choose politics over science any day.

Not that these folks are necessarily any more evil than the rest of us. Short-sighted greed comes as standard equipment on this model, it’s what we are as a species. COP26 failed because the world’s most powerful leaders just don’t feel personally threatened by the crisis.

If only we could threaten them.

If only we could translate the abstract threat of climate change to other people into an immediate threat against things they actually care about on a gut level. Make the hypothetical real, make it unsafe for them to step outside. Target their families. Hold their kin hostage: get us down to 1.5 or your sister comes back in pieces. Let them feel the same desperation as all those people in all those faraway lands they’ve never had to care about.

Mostly revenge fantasy, of course. How would you even do that, when the people you need to threaten have all the power, command the armies and the cops, have a legal monopoly on violence and terrorism? (In fact, I don’t think they even call it “terrorism” when a G8 country does it.) It’s not like any of us are gonna get close enough to throw a rock through Trudeau’s window.

So mostly fantasy—but not all. Because, logistic difficulties aside, I honestly wonder if anything else could work at this point. Even when you sweep away the denialism, facts and science don’t seem to be enough for most people. Even those who accept the reality of climate change—even those who profess to be “gravely concerned”—aren’t willing, for the most part, to do anything significant to fight it. The wildfires, the floods, the pandemics spreading across a warming world; none of it seems to matter to us personally until it threatens us personally. (I do take some hope from the fact that kids these days seem somewhat more worried about the future than their parents; the present they’re growing up in is pretty dire, after all, and the trajectory is not good. But I am profoundly skeptical that we can afford to wait for a new enlightened generation to grow up and fix the problem for us. We’re already out of time.)

We have to be afraid. Somehow, we have to make them afraid.

Of course, we’re going to be rioting in the streets soon enough anyway. When the grid goes down and stays that way, when the coastal cities are flooded and the flyover towns all Lyttonised, when we’ve exhausted the world’s arable land (about thirty years from now, last I heard) and civilization itself begins to collapse (twenty); we’ll be out there with our Molotov cocktails and our boards-with-the-nails-through-‘em. It’s how societies collapse.

Maybe the best we can do is avoid the rush and do it now, when it might still do some good.

Cast your mind back, if you will, to 1965, when Tom Lehrer recorded his live album That Was the Year That Was. Lehrer prefaced a song called “So Long Mom (A Song for World War III)” by saying that “if there's going to be any songs coming out of World War III, we’d better start writing them now.” Another preoccupation of the 1960s, apart from nuclear annihilation, was overpopulation. Stanford University biologist Paul Ehrlich’s book The Population Bomb was published in 1968, a year when the rate of world population growth was more than 2 percent—the highest in recorded history.

Half a century on, the threat of nuclear annihilation has lost its imminence. As for overpopulation, more than twice as many people live on the earth now as in 1968, and they do so (in very broad-brush terms) in greater comfort and affluence than anyone suspected. Although the population is still increasing, the rate of increase has halved since 1968. Current population predictions vary. But the general consensus is that it’ll top out sometime midcentury and start to fall sharply. As soon as 2100, the global population size could be less than it is now. In most countries—including poorer ones—the birth rate is now well below the death rate. In some countries, the population will soon be half the current value. People are now becoming worried about underpopulation.

As a paleontologist, I take the long view. Mammal species tend to come and go rather rapidly, appearing, flourishing and disappearing in a million years or so. The fossil record indicates that Homo sapiens has been around for 315,000 years or so, but for most of that time, the species was rare—so rare, in fact, that it came close to extinction, perhaps more than once. Thus were sown the seeds of humanity’s doom: the current population has grown, very rapidly, from something much smaller. The result is that, as a species, H. sapiens is extraordinarily samey. There is more genetic variation in a few troupes of wild chimpanzees than in the entire human population. Lack of genetic variation is never good for species survival.

What is more, over the past few decades, the quality of human sperm has declined massively, possibly leading to lower birth rates, for reasons nobody is really sure about. Pollution—a by-product of human degradation of the environment—is one possible factor. Another might be stress, which, I suggest, could be triggered by living in close proximity to other people for a long period. For most of human evolution, people rode light on the land, living in scattered bands. The habit of living in cities, practically on top of one another (literally so, in an apartment block) is a very recent habit.

Another reason for the downturn in population growth is economic. Politicians strive for relentless economic growth, but this is not sustainable in a world where resources are finite. H. sapiens already sequesters between 25 and 40 percent of net primary productivity—that is, the organic matter that plants create out of air, water and sunshine. As well as being bad news for the millions of other species on our planet that rely on this matter, such sequestration might be having deleterious effects on human economic prospects. People nowadays have to work harder and longer to maintain the standards of living enjoyed by their parents, if such standards are even obtainable. Indeed, there is growing evidence that economic productivity has stalled or even declined globally in the past 20 years. One result could be that people are putting off having children, perhaps so long that their own fertility starts to decline.

An additional factor in the shrinking rate of population growth is something that can only be regarded as entirely welcome and long overdue: the economic, reproductive and political emancipation of women. It began hardly more than a century ago but has already doubled the workforce and improved the educational attainment, longevity and economic potential of human beings generally. With improved contraception and better health care, women need not bear as many children to ensure that at least some survive the perils of early infancy. But having fewer children, and doing so later, means that populations are likely to shrink.

The most insidious threat to humankind is something called “extinction debt.” There comes a time in the progress of any species, even ones that seem to be thriving, when extinction will be inevitable, no matter what they might do to avert it. The cause of extinction is usually a delayed reaction to habitat loss. The species most at risk are those that dominate particular habitat patches at the expense of others, who tend to migrate elsewhere, and are therefore spread more thinly. Humans occupy more or less the whole planet, and with our sequestration of a large wedge of the productivity of this planetwide habitat patch, we are dominant within it. H. sapiens might therefore already be a dead species walking.

The signs are already there for those willing to see them. When the habitat becomes degraded such that there are fewer resources to go around; when fertility starts to decline; when the birth rate sinks below the death rate; and when genetic resources are limited—the only way is down. The question is “How fast?”

I suspect that the human population is set not just for shrinkage but collapse—and soon. To paraphrase Lehrer, if we are going to write about human extinction, we’d better start writing now.

The red list of Britain’s most endangered birds has increased to 70 species with the swift, house martin, greenfinch and Bewick’s swan added to the latest assessment.

The red list now accounts for more than a quarter of Britain’s 245 bird species, almost double the 36 species given the status of “highest conservation concern” in the first review 25 years ago.

Birds are placed on the red list of the Birds of Conservation Concern report by a coalition of government wildlife bodies and bird charities either because their populations have severely declined in Britain or because they are considered under threat of global extinction.

Swifts and house martins have been moved from the amber list to the red list because their numbers have more than halved – swift populations have fallen by 58% since 1995.

They join other celebrated but now critically endangered long-distance migrants such as the nightingale and cuckoo, whose populations are plummeting owing to a combination of habitat loss, the disappearance of insect food sources and global heating both in British breeding grounds and along migratory routes to sub-Saharan Africa.

Bewick’s swan is another endangered bird that undertakes an epic migration, flying between western Europe and the far north of Russia. It is under pressure from ingesting lead shot, loss of wetlands and climate changes causing shifts in its migrating patterns.

The greenfinch is a familiar garden bird but has moved from the green list of least concern to the red list after its population slumped by 62% since 1993 following an outbreak of the disease trichomonosis. The infection spreads through contaminated food and water – sometimes on bird-feeders – and from birds feeding each other regurgitated food during the breeding season.

While other endangered birds on the red list continue to decline (particularly “farmland” birds such as curlew and turtle dove) Britain’s largest aerial predator has moved off the red list.

The white-tailed eagle is now on the amber list after a successful reintroduction programme that began in 1975, with the raptor spreading across north-west Scotland where there are now 123 breeding pairs. The species was hunted to extinction in 1916 so juvenile birds were first reintroduced from Norway. Offspring from the thriving Scottish population have been restored to the Isle of Wight, with the species likely to be returned to other coastal locations as historical persecution diminishes.

Beccy Speight, the chief executive of the RSPB, one of the report partners, said the biggest-ever red list was more evidence that Britain’s wildlife was in freefall and not enough was being done to reverse declines.

“We are seeing once common species such as swift and greenfinch now becoming rare,” she said. “As with our climate this really is the last chance saloon to halt and reverse the destruction of nature. We often know what action we need to take to change the situation, but we need to do much more, rapidly and at scale.”

Dr Andrew Hoodless, the director of research at the Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust, said: “We need to better understand the effects of climate change on some species, as well as the impacts of changing habitats and food availability along migration routes and in wintering areas of sub-Saharan African migrants. For many red-listed species, however, improving breeding success in the UK is vital – we can and must make real and immediate improvements to this through better engagement with UK farmers, land managers and gamekeepers to encourage adoption of effective packages of conservation measures.”

One small way people can help the house martin is to erect artificial nest cups under the eaves of homes, according to Juliet Vickery, the chief executive of the British Trust for Ornithology.

She said: “It is both sad and shocking to think that the house martin, a bird that often, literally, makes its home under our roof, has become red-listed.”

Red List Breeding Birds: Bird Deaths in Germany Continue

Along with climate change, species extinction is one of the greatest threats to life on earth. For about 50 years, researchers have been documenting the population trends of different animal and plant groups in so-called Red Lists. The new Red List of Breeding Birds in Germany shows that the decline of birds in Germany continues unabated. More than half of the 259 permanently breeding bird species are endangered. Fourteen species have become extinct in Germany so far, and 6 more will probably have to be listed as extinct in the next Red List of breeding birds. This means that breeding bird species are threatened with extinction on an unprecedented scale. Birds of the agricultural landscape as well as insectivores and migratory birds are most threatened. Birds living in forests or residential areas, on the other hand, are on the increase.

[...]

In the reporting period of the new Red List, 33 bird species in Germany are threatened with extinction, and populations are continuing to decline in almost all of them. At 43 percent, almost half of the species that regularly breed in Germany are endangered. Another eight percent are still comparatively common, but their numbers are also declining sharply. "The new Red List shows that species extinction in Germany continues unabated. It has even accelerated in recent years," says Bauer.

In addition, the Red List's threat categories do not reflect the decline of previously non-threatened and common species. Even huge losses of individuals can go unnoticed for a long time in the Red List for species such as starlings or house sparrows, if the species as such are still non-threatened. For example, a study from the Lake Constance region found that the area has lost 120,000 breeding pairs over the past 30 years. Germany-wide, the loss probably amounts to several million individuals.

According to the current Red List, species of the agricultural landscape are particularly threatened: 83 percent of these "open land" species show such high population declines that they are listed as endangered or on the early warning stage. Forty to 50 percent of insectivorous species are disproportionately affected by declines. Migratory birds are by far the hardest hit group, with over 50 percent of species listed as endangered or declining sharply. In contrast, many forest and urban species have increased in recent years – but whether this trend continues remains to be seen.

The causes of the sharp decline in open-land species, insectivores, and migratory birds can be linked to intensive land use-especially agriculture-and overuse of pesticides, as well as hazards and habitat loss on migratory routes. For many species, however, the reasons are complex and sometimes poorly understood. "There's a lot of research that needs to be done. We want to fill some of these knowledge gaps with our new animal monitoring system Icarus. With it, we can literally look over the shoulders of birds in their natural environment and thus find out what threatens them," explains Martin Wikelski, director at the Max Planck Institute for Animal Behavior, who is studying the migratory behavior of blackbirds, cuckoos and storks, and other birds.

In addition to the sharp declines in most bird species, there are also individual bright spots: Where species and their habitat have been specifically protected, populations have recovered. Charismatic birds such as white-tailed eagles, ospreys, cranes and white storks, whose declines had clear and relatively easy-to-mitigate causes, have thus been saved from disappearing. "These examples show that measures to protect species and their habitats and thus protect biodiversity can be successful. What we need now is a national bird rescue program whose measures are actually implemented. Otherwise, we will have to say goodbye to many other bird species in Germany as well," Bauer warns.

“Somewhere out there,” I wrote here two weeks ago, “may lurk what I grimly call the ‘omega variant’ of SARS-CoV-2: vaccine-evading, even more contagious than delta, equally or more deadly. According to the medical scientists I read and talk to … the probability of this nightmare scenario is very low, but it is not zero.”

Indeed. Little did I know, but even as I wrote those words something that appears to fit this description was spreading rapidly in South Africa’s Gauteng province: not the omega variant, but the omicron variant.

As I write today, major uncertainties remain, but what we know so far is not good. People are emotionally predisposed to look on the bright side — we are all sick of this pandemic and want it to be over — so it pains me to write this. Nevertheless, I’ll stick to my policy of applying history to the best available data, even if it means telling you what you really don’t want to hear.

First the data: South African cases were up 39% on Friday, to 16,055. The test positivity rate rose from 22.4% to 24.3%, suggesting that the true case number is rising even faster. A Lancet paper suggests that Omicron is likely by far the most transmissible variant yet. There are three possible explanations for this:

1. A higher intrinsic reproduction number (R0),

2. An advantage in “immune escape” to reinfect recovered people or evade vaccines, or

3. Both of the above.

An important preprint published on Dec. 2 pointed to immune escape. South Africa’s National Institute for Communicable Diseases has individualized data on all its 2.7 million confirmed cases of Covid-19 in the pandemic. From these, it identified 35,670 suspected reinfections. (Reinfection is defined as an individual testing positive for Covid-19 twice, at least 90 days apart.) Since mid-November, the daily number of reinfections in South Africa has jumped far faster than in any previous wave. In November, the hazard ratio was 2.39 for reinfection versus primary infection, meaning that recovered individuals were getting Covid at more than twice the rate of people who had never had Covid before. And this was when omicron made up less than a quarter of confirmed cases. By contrast, the same study found no statistically significant evidence that the beta and delta variants were capable of reinfection. And, crucially, at least some of these new infections are leading to serious illness. On Thursday, the number of Gauteng patients in intensive care for Covid almost doubled from 63 to 106.

Data from a private hospital network in South Africa that has over 240 patients hospitalized with Covid indicate that 32% of the hospitalized patients were fully vaccinated. Note that around three-quarters of the vaccinated in South Africa received the Pfizer Inc.-BioNTech SE vaccine. The rest got the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

Yet these are not the data that worried me the most last week. Those had to do with children. Between Nov. 14 and 28, 455 people were admitted to hospital with Covid-19 in Tshwane metro area, one of the largest hospital systems in Gauteng. Seventy (15%) of those hospitalized were under the age of five; 117 (25%) were under 20. And this is not just a story of precautionary hospitalizations. Twenty of the 70 hospitalized toddlers progressed to “severe” Covid. Up until Oct. 23, before experts estimate omicron began circulating, under-fives represented only 1.8% of cumulative Covid hospital admissions in South Africa. As of Nov. 29, 10% of those now hospitalized in Tshwane were under the age of two.

If this trend holds as omicron spreads to advanced economies — and it is spreading very fast, confirming omicron’s high transmissibility — the market impact could be much bigger than is currently priced in. Unlike with the delta wave, many schools would return to hybrid instruction, parents would withdraw from the labor force to provide childcare and consumption patterns would again shift away from retail, hospitality and face-to-face services. Hospital systems would also face shortages of pediatric intensive care beds, which have not been much needed in prior Covid waves.

South Africa’s top medical advisor Waasila Jassat noted on Dec. 3 that hospitalizations on average are less severe than in previous waves and hospital stays are shorter. But she also noted a “sharp” increase in hospital admissions of under-fives. Children under 10 represent 11% of all hospital admissions reported since Dec. 1.

Here’s what we don’t know yet. We do not know how far prior infection and vaccination will protect against severe disease and death in northern hemisphere countries, where adult vaccination rates are much higher than in South Africa (just 24%). And we do not know if omicron will prove as aggressive toward children in those countries, especially the very young children we have not previously contemplated vaccinating. (Because South Africa has limited testing capacity, we do not know the total number of under-fives infected with omicron in Gauteng, so we do not know what percentage of children are falling sick.) We may not know these things for another week, possibly longer. So panic is not yet warranted. Nor, however, is wishful thinking. It may prove a huge wave of mild illness, signaling the final phase of the transition from pandemic to endemic. But we don’t know that yet.

Now the history. First, it makes all the difference in the world whether or not children fall gravely ill in a pandemic. Covid has so far spared the very young to an extent rarely seen in the recorded history of respiratory disease pandemics. (The exception seems to be the 1889-90 “Russian flu,” which modern researchers suspect was in fact a coronavirus pandemic.) The great influenza pandemics of 1918-19 and 1957-58 killed the very young as well as the very old. The former also carried off young adults in the prime of life. The latter caused significant excess mortality among teenagers. Up until this point, Covid was the social Darwinist disease: It disproportionately killed the old, the sick and the gullible (the vulnerable people who allowed themselves to be persuaded that the vaccine was more dangerous than the virus).

A hundred years ago, many experts would have hailed such a disease for the same reasons they promoted eugenics. We think differently now. However, emotionally and rationally, we still dread the deaths of children much more than the old, the sick and the foolish. The moment children become seriously ill — as has already happened in Gauteng — the nature of the pandemic fundamentally alters. Risk aversion will be far higher in the Ferguson family, for example, if its youngest members are vulnerable for the first time.

The second historical point is that this may be how our age of globalization ends — in a very different way from its first incarnation just over a century ago. The first age of globalization, from the 1860s until 1914, ended with a bang, not a whimper, with the outbreak of World War I. Within a remarkably short space of time, that conflict halted trade, capital flows and migration between the combatant empires. Moreover, the war and its economic aftershocks strengthened and ultimately empowered new political movements, notably Bolshevism and fascism, that fundamentally repudiated free trade and free capital movements in favor of state control of the economy and autarky. By 1933, the outlook for liberal economic policies seemed so utterly hopeless that, in a lecture he gave in Dublin, even John Maynard Keynes threw in the towel and embraced economic self-sufficiency.

Abstract

The history of the Earth system is a story of change. Some changes are gradual and benign, but others, especially those associated with catastrophic mass extinction, are relatively abrupt and destructive. What sets one group apart from the other? Here, I hypothesize that perturbations of Earth’s carbon cycle lead to mass extinction if they exceed either a critical rate at long time scales or a critical size at short time scales. By analyzing 31 carbon isotopic events during the past 542 million years, I identify the critical rate with a limit imposed by mass conservation. Identification of the crossover time scale separating fast from slow events then yields the critical size. The modern critical size for the marine carbon cycle is roughly similar to the mass of carbon that human activities will likely have added to the oceans by the year 2100.