Hightor agrees (rather violently) with me on this point.

If I misstated your position, then I am sorry (and I am certainly not going to argue with you about what your position is... I hate it when people do this). I believe I remember you posting a graph where you made this claim. I can't find it now, nor do I want to try. You can just tell me what you believe.

1) The fact is that over the past 50 years Americans are working significantly fewer hours now. The same is true looking back 100 years or 200 years.

2) The time my grandmother spent scrubbing clothes on a washboard does not count as leisure time. Hightor agrees (rather violently) with me on this point. Nor does time spent fixing your house or mowing your lawn.

3) Economists (the experts who measure leisure time) tell us that leisure time has significantly risen over the past 50 and 100 years.

If we agree on all of these things, then I am good and I offer apologies for misstating your position.

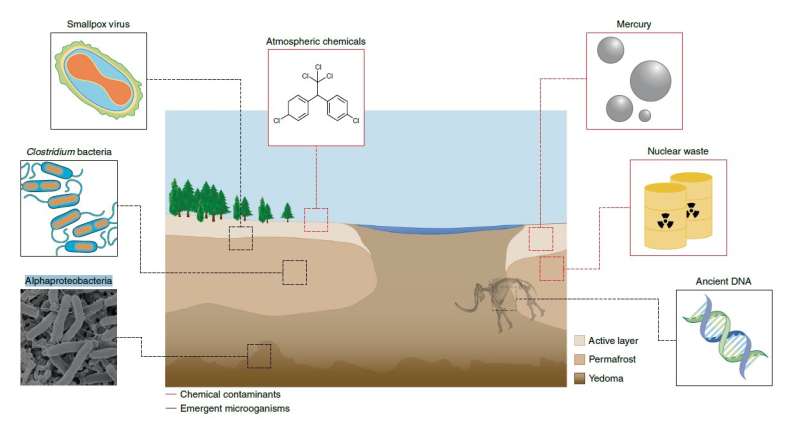

When considering the implications of thawing permafrost, our initial worries are likely to turn to the major issue of methane being released into the atmosphere and exacerbating global warming or issues for local communities as the ground and infrastructure become unstable. While this is bad enough, new research reveals that the potential effects of permafrost thaw could also pose serious health threats.

As part of the ESA–NASA Arctic Methane and Permafrost Challenge, new research has revealed that rapidly thawing permafrost in the Arctic has the potential to release antibiotic-resistant bacteria, undiscovered viruses and even radioactive waste from Cold War nuclear reactors and submarines.

Permafrost, or permanently frozen land, covers around 23 million square kilometers in the northern hemisphere. Most of the permafrost in the Arctic is up to a million years old—typically the deeper it is, the older it is.

In addition to microbes, it has housed a diverse range of chemical compounds over millennia whether through natural processes, accidents or deliberate storage. However, with climate change causing the Arctic to warm much faster than the rest of the world, it is estimated that up to two-thirds of the near-surface permafrost could be lost by 2100.

Thawing permafrost releases greenhouse gases—carbon dioxide and methane—to the atmosphere, as well as causing abrupt changes to the landscape.

However, research, published recently in Nature Climate Change, found the implications of waning permafrost could be much more widespread—with potential for the release of bacteria, unknown viruses, nuclear waste and radiation, and other chemicals of concern.

The paper describes how deep permafrost, at a depth of more than three meters, is one of the few environments on Earth that has not been exposed to modern antibiotics. More than 100 diverse microorganisms in Siberia's deep permafrost have been found to be antibiotic resistant. As the permafrost thaws, there is potential for these bacteria to mix with meltwater and create new antibiotic-resistant strains.

Another risk concerns by-products of fossil fuels, which have been introduced into permafrost environments since the beginning of the industrial revolution. The Arctic also contains natural metal deposits, including arsenic, mercury and nickel, which have been mined for decades and have caused huge contamination from waste material across tens of millions of hectares.

Now-banned pollutants and chemicals, such as the insecticide dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane, DDT, that were transported to the Arctic atmospherically and over time became trapped in permafrost, are at risk of re-permeating the atmosphere.

In addition, increased water flow means that pollutants can disperse widely, damaging animal and bird species as well as entering the human food chain.

There is also greater scope for transportation of pollutants, bacteria and viruses. More than 1000 settlements, whether resource extraction, military and scientific projects, have been created on permafrost during the last 70 years. That, coupled with the local populace, increases the likelihood of accidental contact or release. Despite the findings of the research, it says the risks from emergent microorganisms and chemicals within permafrost are poorly understood and largely unquantified. It states that further in-depth research in the area is vital to gain better insight into the risks and to develop mitigation strategies.

The review's lead author, Kimberley Miner, from NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said, "We have a very small understanding of what kind of extremophiles—microbes that live in lots of different conditions for a long time—have the potential to re-emerge. These are microbes that have coevolved with things like giant sloths or mammoths, and we have no idea what they could do when released into our ecosystems.

"It's important to understand the secondary and tertiary impacts of these large-scale Earth changes such as permafrost thaw. While some of the hazards associated with the thaw of up to a million years of material have been captured, we are a long way from being able to model and predict exactly when and where they will happen. This research is critical."

ESA's Diego Fernandez added, "Research being conducted as part of the ESA–NASA Arctic Methane and Permafrost Challenge within our Science for Society program is vital to understanding the science of the changing Arctic. Thawing permafrost clearly poses huge challenges, but more research is needed. NASA and ESA are joining forces to foster scientific collaboration across the Atlantic to ensure we develop solid science and knowledge so that decision-makers are armed with the correct information to help address these issues."

Superpowers aren’t impressive.

Italy, Greece, Ethiopia, Egypt, Britain, Spain, Portugal; they’ve all ruled the world for a time before sliding back to just regular-ol’-nation status.

Now it’s America’s turn.

The United States is going to collapse.

This isn’t a fear-mongering statement.

Just a fact.

Everyone knows it.

Whether in five years or fifty, the days of America-as-global-superpower are numbered.

In the same way that Rome pulled back its troops from Alexandria in Egypt and the Scottish borders in Britain, the American military-industrial complex will continue the work started in Afghanistan and eventually withdraw its 800 global military bases in order to make a last-ditch effort to enslave its own people in a soft-totalitarian panopticon surveillance state.

And then it will collapse.

Diehard nationalists insist it could never happen, but the signs of American collapse are obvious:

1. Wealth inequality

American income inequality is growing, too.

Higher than the Roman Empire’s, in fact.

The stats on wealth inequality are crazy. Please read them all.

Nevermind the Gilded Age of corporate tyrants like Vanderbilt and Carnegie and Rockefeller — today’s billionaires control more wealth and political power than the monopolists of the past could ever have dreamed.

And while extreme right-wingers are quick to shout “Communism! Socialism!” they fail to realize we’re not advocating central ownership or central control of the economy. That’s what billionaires are working on.

2. Debt

The numbers are staggering:

America has nearly $29 trillion in federal debt.

Total consumer debt sits at $14.9 trillion.

Half a million American families are systemically forced into bankruptcy every year.

Don’t listen to those nutty Modern Monetary Theory boosters who think we can pile up debt forever and it will never destroy our society.

The bell will toll, and it will toll for us.

Don’t get me wrong, the MMTers are technically right — we can print money forever. But every unbacked printed dollar erodes trust and purchasing power.

When society is built on a literal lie, it’s only a matter of time before it falls.

3. Economic Instability

Because of how hyper-elites have structured the economy, we’re stuck with permanent economic instability — insane asset bubbles, followed by massive crashes that hurt those who a.) didn’t benefit in the good times, and b.) suffer most in the bad times.

While it’s never occurred to the corporations who control our countries, people want to live in economically stable places.

Because America refuses to deliver on true, long-term economic stability for the majority, it’s no wonder we’re currently seeing a national strike, and why many of us with the power to do so have already moved overseas.

4. Homeownership in Crisis

Rentership, too.

I’ve been sounding the alarm on this one for a while — people have no idea the tidal wave that’s about to shatter the American middle class once and for all.

House prices are going to $10 million in our lifetime, and if we don’t ban for-profit residential real estate investment and overthrow the corrupt zoning boards that keep young families from building homes they can afford, we will see a houselessness crisis never witnessed before in human history.

5. Crony Corporate Politics

Democracy, of course, has never existed in America, but the corporate oligarchy now owns Congress lock, stock, and barrel.

There’s honestly no point in voting unless it’s with your money.

6. Environmental Instability

When I was younger, my wife and I visited Tikal in Guatemala, the New York City of the pre-Columbian Maya civilization.

They destroyed their environment, and then it destroyed them.

It’s really simple: Nations that don’t protect people, wildlife, soil, water, and air eventually go extinct.

It’s not personal, it’s science.

As commenter Nikos Papakonstantinou put it:

You can’t eat, drink, or breathe money.

It takes 1,000 years for nature to grow 3cm of topsoil, and America has managed to burn through several feet in the past century.

Now, America only has sixty harvests left.

(An excellent book on the topic is Empires of Food: Feast, Famine, and the Rise and Fall of Civilization.)

7. The Vampire Economy

Let’s face it, the American productive economy is dead.

Most of the major brands are zombie companies that burn cash and have never been profitable a day in their short-lived corporate lives.

Rather than producing products and services of real value, corporate America is just a giant game of extractivism, a dung pile of rent-seeking skimmers who blood-suck time and wealth from the productive poor while contributing nothing of real value:

Landlords

Bankers

Stock investors

Crypto speculators who would rather treat Bitcoin as a Ponzi scheme instead of freedom money to stave off abhorrent central bank surveillance currencies.

When a nation stops creating real value and starts eating itself like a snake, its days are mathematically numbered.

8. Mass Hysteria

Looking at you, anti-vaxxers.

And Q-Anoners.

And cancel culturists.

And people who vote for Republicans and Democrats.

America is now filled with conspiracy theorists and people who draw the line and refuse to dialogue with people outside of their own box. This signals a total breakdown in personal understanding, civic goodwill, institutional trust, and national unity.

9. Screen Addiction

The invention of the smartphone will surely go down in history as one of the most destructive pieces of technology ever invented.

Homo sapiens are in no way adapted for the super-stimulus of digital outputs.

Between social media, streaming, porn, gaming, and shopping addictions, we’re breaking our necks, frying our eyes, and shattering any sense of offline meaning or belonging.

Just wait until Gen Z and Gen Alpha are in charge.

10. Individualism

America is a culture (from the Latin cultus, where we derive the word “cult”) built on the myth of rugged individualism, of “one for me, and all for me.”

It’s a dog-eat-dog, survival-of-the-fittest, winner-take-all, loser-dies-in-poverty cult where the rich prey on the poor and the masses suffer so the elites can live a little better a little longer.

America is a piece of glass that has been shattered into 331 million shards, each stabbing the next in a frantic fight for survival.

Only a hard fire can forge the pieces back together.

There are those who believe a Canadian living in Europe shouldn’t have the right to comment on America at all, but of course, those people are usually nationalists who fail to see we live in a hyper-connected world where everyone’s choices affect everyone else. The failure to understand this is yet another symptom of hyper-individualism.

America is a fractured, atomized nation, with each member so hell-bent on self-actualization, obsessed with concocting a singularly unique identity, and blinded by the idea that autonomy and freedom are the same thing.

Because the nation cannot fathom it shares one common freedom, it simply cannot surrender any amount of selfhood to the collective, despite the fact that human togetherness is the #1 thing correlated to human happiness.

The end isn’t the end

All empires fall. It’s a non-negotiable. It’s just a matter of when, how, and how hard.

Collapse doesn’t mean disappearance.

And it doesn’t necessarily mean a total dystopian hellscape like the Book of Eli.

But it does mean a loss of global superpower status and all the unfair advantages that came along with it, like currency supremacy and cheap goods. It means a country seriously diminished, greatly impoverished, wracked with crime and disease and exploitation, and subject to the whims of foreign corporatists hell-bent on extraction.

You know, like much of the rest of the world.

Normally, my articles outline a challenge facing society and offer some proposals for how to fix it. This is one of those rare posts that just points out the macro factors that will lead to the inevitable fall of America.

Collapse shouldn’t sit well with readers.

Everyone needs to be working on solutions. (And yes, peacefully turning the American landmass into a dozen or so new nations is highly preferable to a bloody second civil war.)

The goal, of course, shouldn’t be to maintain a hyper-violent military empire and coercive global economic grasp on others. It’s time for new ideas, and ancient ideas, and real servant-hearted leadership, and working together.

We shouldn’t mourn the loss of corporate-controlled America as the global superpower. It’s a monstrous menace to global freedom and widest-spread wellbeing.

Now, does that mean this is China’s century?

Maybe.

They already own America’s largest pork producer, and Canada’s largest dairy farm, but a third of their domestic economy is a giant real estate bubble that could seriously slow their growth.

China’s rise to global super-power will all depend on their continued colonization of Africa and their ability to debt-trap the world via their Belt and Road Initiative — practicing capitalism abroad to enforce fake communism at home.

Clearly, the world doesn’t need or want a conformist culture to dictate global policy. People often say that America is still the world’s “best hope for freedom.” But as billions of people who’ve endured the heavy hammer of the American military-industrial complex can attest, it’s simply not true.

Modern corporate America doesn’t equal hope. No self-centered human institution can ever deliver the freedom that people truly need.

Don’t worry, America itself isn’t going anywhere

After all, Rome’s as gorgeous as ever.

And Athens is amazing, albeit under-maintained.

America the superpower is waning, but that doesn’t mean Concord won’t always be a gorgeous place to visit.

Texas will probably always be the BBQ capital of the world (or at least until the radical left bans meat or the radical right makes beef-raising an environmental impossibility.)

Maybe Canada or Mexico will annex America and finally provide free healthcare to the poor?

And if the fifty states decide to split up, which they almost certainly will in time, you never know if a united Maine and New Hampshire might rule a world in desperate need of lumber and freshwater.

Or maybe we just don’t need superpowers anymore.

Maybe it’s time for Tinyism and a million little democracies.

Either way, the United States of America won’t be around to see it happen.

Chevron has long dominated oil production in Lost Hills, a massive fossil fuel reserve in Central California that was accidentally discovered by water drillers more than a century ago. The company routinely pumps hundreds of thousands of gallons of water mixed with a special concoction of chemicals into the ground at high pressure to shake up shale deposits and release oil and gas. The process — called hydraulic fracturing, or fracking — produces thousands of barrels of oil every day. But it also leaves the company saddled with millions of gallons of wastewater laced with toxic chemicals, salts, and heavy metals.

Between the late 1950s and 2008, Chevron disposed much of the slurry produced in Lost Hills in eight cavernous impoundments at its Section 29 facility. Euphemistically called “ponds,” the impoundments have a combined surface area of 26 acres and do not have synthetic liners to prevent leaking. That meant that over time, salts and chemicals in the wastewater could leak into the ground and nearby water sources like the California Aqueduct, a network of canals that delivers water to farms in the Central Valley and cities like Los Angeles.

And that’s exactly what happened, according to new research published in the academic journal Environmental Science & Technology this month. Carcinogenic chemicals like benzene and toluene as well as other hydrocarbons have been detected within a half a kilometer of the facility. About 1.7 kilometers northwest of the facility, chloride and salt levels are more than six times and four times greater than background levels, respectively. The research leaves little doubt: The contaminants are migrating toward the aqueduct.

“Clearly, there’s impact to groundwater resources there,” said Dominic DiGiulio, lead author of the paper and a researcher at the nonprofit Physicians, Scientists, and Engineers for Healthy Energy. “At the section 29 facility, you have to go 1.8 kilometers away from the facility to find background water quality. That’s pretty far.”

The facility shuttered in 2008, and it no longer accepts wastewater. Chevron has continued to monitor the contaminant plume and submits yearly water quality reports to the Central Valley Regional Water Quality Control Board, a local groundwater quality regulator. In a 2019 report, the company claimed it would cost more $800,000 to monitor the plume and report to the regulator for the next 30 years.

Jonathan Harshman, a spokesperson for Chevron, said the company was reviewing the study and that it “has complied and will continue to comply with” the Central Valley Water Board’s requirements for maintaining and monitoring leaks at the Section 29 facility.

The Section 29 facility isn’t an isolated case. Between 1977 and 2017, over 16 billion barrels of oilfield wastewater was disposed in unlined ponds in California. The vast majority of these are located outside of Bakersfield in the state’s Central Valley: According to DiGiulio’s research, there are at least 1,850 wastewater ponds in the San Joaquin Valley’s Tulare Basin. Of those, 85 percent are unlined and about one-fourth are active, like the Section 29 facility. However, despite not being operational, many of them may be leaking into the ground. Wells that monitor groundwater quality are few and far between, so it’s difficult to know the exact scope of the pollution. But DiGiulio warns that the ponds constitute “a potential wide-scale legacy groundwater contamination issue.”

This month’s study is the first to quantify the number of unlined pits in California and analyze their effects on groundwater. The findings bolster 2015 research by California Council on Science & Technology and the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, which concluded that unlined wastewater pits posed a threat to groundwater sources and called for investigations into whether contaminants have leaked from disposal ponds. Research conducted by the United States Geological Survey for the Central Valley Water Board has also found evidence of oil and gas wastewater contaminating groundwater.

Disposal of oil and gas wastewater is a national problem. Companies use anywhere between 1.5 million and 16 million gallons of water to frack a single well, and they have struggled to find economical and environmentally safe ways to dispose of the toxic fluid. The vast majority of the wastewater — both in California and nationally — is injected underground into porous rock formations, but companies also recycle and reuse the water to grow crops, de-ice roads, and suppress dust. California appears to be the only state that permits operators to store the waste in unlined pits, according to DiGiulio.

Patrick Pulupa, an executive officer with the Central Valley water board, defended the practice and noted that the wastewater ponds are only allowed in areas where the groundwater has been deemed too salty for irrigation or household use. In cases where the contamination has threatened usable water, he said, the Board has cracked down with cease-and-desist and investigative orders. “Board staff continue to look in detail at whether additional produced water discharges are a threat to usable groundwater and will continue to issue enforcement orders where appropriate,” he added.

The definition of groundwater that is “too salty” for use varies across California. Federal regulations consider water with less than 10,000 milligrams of dissolved solids per liter of water as protected for potential irrigation, industrial, and household use. As a result, companies are typically not allowed to dispose of wastewater in underground formations if it threatens groundwater that is below the 10,000 mg/L threshold — unless they secure an exemption from the state.

For unlined wastewater pits, however, that threshold has been set at 3,000 mg/L. The inconsistency allows oil and gas companies to pollute potential sources of groundwater, according to DiGiulio, and “appears to be the major driver for this continued disposal practice.”

“The fundamental problem is that the condition under which California groundwater is to be protected is not sufficiently stringent,” he said, adding that the state water board has the authority to increase the threshold to better protect groundwater near wastewater pits and should do so.

From Pulupa’s perspective, the 3,000 mg/L threshold is not dissimilar to the standard for disposal into underground formations in practice. Though federal regulations set the limit at 10,000 mg/L, companies are routinely granted exemptions if they can demonstrate that the groundwater is not expected to be used as a source of drinking water. The exemptions apply if the water has a dissolved solids concentration between 3,000 and 10,000 mg/L, and the controversial practice has allowed oil and gas companies to pump wastewater into hundreds of aquifers across the country. As a result, the “protective standards are relatively similar,” and the Central Valley Water Board is “unaware of any effort” to modify the definition of protected groundwater near wastewater pits, he said.

As global warming continues to worsen, the effects of climate change will force people worldwide to migrate to new areas to survive. Africa is expected to be among the hardest hit by climate change, and if actions aren't taken quickly, by 2050 the situation will be so dire that up to 86 million people will have to leave their homes, a new World Bank report found.

For this report, the World Bank, an international development organization that lends money to nations to help improve their standard of living, specifically looked in the West African and Lake Victoria Basin regions of the continent, which are home to millions of people.

The regions, according to the report, have contributed the least to global warming, yet are set to experience "the most devastating impacts of climate change."

Based on how climate change is being handled and the socioeconomic statuses of the regions, the World Bank predicts that climate migration "hot spots" in the areas could begin in the next nine years.

"Without concrete climate and development action, West Africa could see as many as 32 million people forced to move within their own countries by 2050," a press release about the report states. "In Lake Victoria Basin countries, the number could reach a high of 38.5 million."

Out of the five countries that make up the Lake Victoria Basin — Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi — Tanzania will be most impacted by forced migration, the report says, with up to 16.6 million people being impacted. And in West Africa, Niger and Nigeria will see the largest numbers of internal climate migrants.

Along with the more widely-discussed impacts of climate change, such as droughts and sea level rise, there are more subtle effects that will force people from their regions. Many areas will see spikes in temperature, more extreme weather events and land loss, while others will also see water and food scarcity, reduced agriculture, lower ecosystem productivity and higher storm surges, the report says.

All of these factors will make many regions unlivable, and will push people to other areas that are more survivable. But as people migrate to escape these fragile environments, other issues already being experienced — poverty, conflict and violence — will only get worse, the report says.

It's not just these regions in Africa facing this issue — millions of others around the world will be forced to migrate at the same time. In September, another report by the World Bank warned that about 216 million people from these regions, as well as North Africa, Latin America, Eastern Europe, Central Asia, South Asia, East Asia and the Pacific, will also be on the move.

World Bank published its newest findings ahead of the COP26 United Nations climate summit, which is set to begin on October 31. There, nearly every nation in the world will discuss how well they have upheld their promises to mitigate climate change.

As part of the Paris Climate Agreement, global leaders are supposed to be implementing policies and developing strategies to limit global warming to less than 2° Celsius compared to pre-industrial levels. If current policies do not change, however, it will lead to 2.9° Celsius, scientists say.

To prevent the soon-to-come mass migration, the World Bank said that the world must take "bold, transformative" actions, and quickly. If nations are able to do so, they could reduce the scale of climate migration by 30% in the Lake Victoria region and as much as 60% in West Africa, the report says.

The World Bank said at the forefront of these efforts should be cutting down on greenhouse gas emissions to limit global warming, a promise of the Paris Climate Agreement. Governments are also urged to develop resilient and inclusive climate migrations plans and invest in research and tools to better prepare for the future. Lastly, the World Bank said that investments must be made to help and encourage people get sustainable "climate smart" jobs.

But for some areas, the effects are already pushing people to leave.

Around 10,000 people have left Central America in an attempt to escape the effects of climate change. The region was blasted by two catastrophic category 4 hurricanes, Eta and Iota, just two weeks and 15 miles apart. Nearly 600,000 people had been displaced by the storms, and thousands of homes were completed destroyed.

Their migration to Mexico and the U.S. for help and opportunities offered a dire warning about what the future may look like without immediate governmental climate action.

Kayly Ober, senior advocate and program manager of the Climate Displacement Program at Refugees International, previously told CBS News that these kinds of devastating events and the impending migrations thereafter will only increase.

"We need to realize that climate change impacts are already influencing decisions to migrate today, and ensure that people moving are able to access safe and dignified pathways in their own country and abroad," Ober said in February. "...I am concerned that climate change impacts will only increase in frequency and intensity, and that without proper support or policy intervention, people will have to make the difficult to decision to move."

Boris Johnson has issued an apocalyptic warning that civilisation could collapse “like the Roman Empire” unless runaway climate change is stopped.

En route to the G20 summit in Rome, the prime minister said the world could “go backwards” – as it did after its famous empire fell – unless a deal to halt the climate emergency is struck at the Cop26 summit.

“Humanity, civilisation and society can go backwards as well as forwards and when they start to go wrong, they can go wrong at extraordinary speed,” Mr Johnson said.

“You saw that with the decline and fall of the Roman Empire.”

And he added: “It’s true today that, unless we get this right in tackling climate change, we could see our civilisation, our world, also go backwards.”

“We could consign future generations to a life far less agreeable than our own,” he said – pointing to shortages of food and shortages of water and conflict caused by climate change.

“There is absolutely no question that this is a reality we must face.”

Pointing again to the example of the end of the Romans, the prime minister said: “People lost the ability to read and write and the ability to draw properly. They lost the way to build in the way that the Romans did.”

He also compared the situation to a football match, saying: “If this was half time, I would say we were about 5-1 down. We have a long way to go, but we can do it.”

Ahead of urging other G20 leaders to beef up their CO2-cutting commitments, Mr Johnson told reporters: “We need to spit out our oranges and get back on the pitch.”

Admitting his own “road to Damascus” conversion - after a journalism career in which he scoffed at climate change - Mr Johnson said the key moment had only come after he became prime minister.

He said he was briefed by government scientists soon after arriving in Downing Street, in 2019.

“I got them to run through it all and, if you look at the almost vertical kink upward in the temperature graph, the anthropogenic climate change, it’s very hard to dispute,” he said.

“That was a very important moment for me. That’s why I say what I say.”

Asked if he was eating less meat as a way to cut his carbon footprint, Mr Johnson replied: “I’m eating a bit less of everything, which may be an environmentally friendly thing to do.”

Whether it’s the apocalyptic wildfires that once again ravaged California and the West this summer, a heat dome over the Pacific Northwest that made parts of Canada feel like Phoenix on the Fourth of July or the devastating floods in my state of Pennsylvania after Hurricane Ida dumped months’ worth of rainfall in a few hours, it is clear that dangerous climate change is upon us.

One can no longer credibly deny that climate change is real, human-caused, and a threat to our civilization. That means that the forces of inaction — the fossil fuel interests and the front groups, organizations and mouthpieces-for-hire they fund — have been forced to turn to other tactics in their effort to keep us dependent on fossil fuels.

These tactics include deflection (focusing attention entirely on individual behavioral change so as to steer the societal discourse away from a discussion of the needed policies and systematic changes), division (getting climate advocates fighting with each rather than speaking with a united voice), and the promotion of doomism (convincing some climate advocates that it’s too late to do anything anyway).

But the D-word du jour is delay. And we’ve become all too familiar with the lexicon employed in its service: “adaptation,” “resilience,” “geoengineering” and “carbon capture.” These words offer the soothing promise of action, but all fail to address the scale of the problem.

Adaptation and resilience are important. We must cope with the detrimental effects of climate change that are already baked in — coastal inundation and worse droughts, floods and other dangerous weather events. But if we fail to substantially reduce carbon emissions and stem the warming of the planet, we will exceed our collective adaptive capacity as a civilization.

When fossil fuel-friendly Republican Sen. Marco Rubio tells Floridians that they must simply “adapt” to sea level rise (how? By growing fins and gills?), he’s trying to sound as if he’s got a meaningful solution when, in fact, he’s offering only empty rhetoric and a license for polluters to continue with business as usual. It’s a delay tactic.

What about geoengineering? Should we engage in an enormous, unprecedented and uncontrolled experiment to further intervene with our planetary environment by, for example, shooting sulfur particulates into the stratosphere to block out the sun in hopes of somehow offsetting the warming effect of increasing carbon pollution?

The law of unintended consequences almost certainly ensures that we will screw up the planet even more. The idea of geoengineering also grants license for continued carbon pollution. There’s a reason Rex Tillerson, former ExxonMobil CEO and Donald Trump’s secretary of State, has dismissed the climate crisis as simply an “engineering problem.” If we can simply clean up our act down the road, why not continue to burn fossil fuels? This, too, is a delay tactic — one that buys time for polluters to continue to make billions in profits as we mortgage the future habitability of the planet.

And what about “carbon capture” and the promise of “net zero” emissions by mid-century? Reaching zero emissions by 2050 will indeed be necessary to avert catastrophic planetary warming of more than 1.5 degrees Celsius. But it is hardly sufficient. We must also cut emissions in half by 2030 to hold warming below the danger limit of 1.5 degrees Celsius. Merely committing to the former, but not the latter, is like making a New Year’s resolution to lose 15 pounds without any plan to alter your diet and exercise regimen in the months ahead.

Furthermore, understand that the “net” in “net zero” is doing quite a bit of work, for implicit in the word is the notion that we can continue to burn fossil fuels if we can find a way to remove them just as quickly. To quote Will Smith’s Genie in the movie “Aladdin,” there’s “a lot of gray area” in that word. It allows politicians to make vague promises of technological innovation, i.e., carbon capture, that would potentially remove billions of tons of carbon dioxide a year from the atmosphere in the future. Yet there is no precedent for deploying such technology on such a massive scale.

It’s really easy to put carbon pollution into the atmosphere but really hard to take it back out and safely bury it for the long term. Nonetheless, the promise of carbon capture and net zero emissions decades from now allows politicians to kick the can so far down the road you can barely see it. That’s another masterful delay tactic.

Look no further than Australia, a country that deserves better than the feckless coalition government that currently reigns. The parties there have reluctantly and conditionally agreed only to the weak commitment of net zero emissions by mid-century. And their commitment to reduce carbon emission by a paltry 26% to 28% by 2030 is half what other industrialized nations such as the U.S., Britain and the European Union have committed to.

A newly released report based on leaked documents shows that the Australian government sought to water down an upcoming U.N. climate recommendation to phase out coal- and gas-fired power stations. Saudi Arabia and Russia — two countries that have worked to sabotage international climate action in the past — have made a mockery of the current climate negotiations by agreeing only to a laughably delinquent 2060 date for reaching net zero emissions.

Even countries that have made bold commitments are still suffering from an “implementation gap” that must be closed, a disconnect between what they’ve promised and what they’re currently delivering. The Biden administration is currently hampered by Sen. Joe Manchin, a coal-state Democrat who stands in the way of the administration’s clean energy agenda. The E.U. and Britain, meanwhile, are flirting with new oil and gas pipelines even as the International Energy Agency has said there can be no new fossil fuel development if we are to avert catastrophic warming.

The U.N. climate summit in Glasgow can still lay out a path forward, if a narrow one, to a livable clean energy future. But we cannot afford to fall victim to delay tactics. We must hold our policymakers accountable for representing the public interest rather than polluting interests. This is the last best opportunity for averting climate disaster.

As world leaders and delegations gather in Glasgow for the UN Climate Change Conference, here is our postcard from Siberia, highlighting the way the planet is visibly changing in front of our eyes.

In our time, we see all around troubling events unfamiliar to our parents and grandparents.

Statistics show that in 2020, Russia was 3.2C degrees warmer than the average in the three decades to 1990. Winter temperatures are milder than ever, with air warming up to 5C above the norm.

The number of forest fires have increased four-fold, while storms and hurricanes are ten times more likely.

In 2003 President Vladimir Putin quipped that ‘2 to 3 degrees [of global warming] wouldn't hurt. We'll spend less on fur coats’.

While he will not travel to Glasgow, he said recently: ‘Change and environmental degradation are so obvious that even the most careless people can no longer dismiss them.

‘One can continue to engage in scientific debates about the mechanisms behind the ongoing processes, but it is impossible to deny that these processes are getting worse, and something needs to be done.

‘Natural disasters such as droughts, floods, hurricanes, and tsunamis have almost become the new normal, and we are getting used to them.

‘Suffice it to recall the devastating, tragic floods in Europe last summer, the fires in Siberia - there are a lot of examples.’

Here are eight big ways that Siberia is changing

1. BUBBLING METHANE

Siberia’s stark warning to Scotland for Cop26: climate change in the planet’s last great wilderness

Our pictures are from two separate locations thousands of kilometres apart: the Arctic Ocean, and the world’s oldest and deepest freshwater reservoir, Lake Baikal.

In both cases methane is being released in a way not seen just a generation ago due to the rapid thawing of permafrost, which had sealed the gas for tens of thousands of years - until now.

Discharges in the Laptev and East Siberian seas observed from the Akademik Keldysh research vessel showed high methane concentrations from underwater craters and 'super seep holes' in the thawing ocean floor permafrost.

Bubble clouds are rising from a depth of around 300 metres (985ft) along a large undersea slope, as our view shows.

'They look like holes in the permafrost and, as our studies showed, they were formed by massive methane discharge,' explained Professor Igor Semiletov. 'Two more powerful seeps emitting methane through iceberg furrows were also discovered in the East Siberian Sea.'

Scientists identified half a dozen “mega seeps” and found concentration of atmospheric methane above these fields reaching 16-32ppm (parts per million). This is up to 15 times the planetary average of 1.85ppm.

We now go south to majestic Baikal where unworldly images are seen beneath the frozen ice on a lake containing 20 per cent - yes, one fifth - of the world’s unfrozen freshwater.

These unworldly under-ice shapes are stunningly natural artistry; yet beneath the crystal clear frozen surface they also signal leaking methane.

The lake has some two dozen major deepwater methane seeps - below 380 metres (1,250 ft) - and hundreds of shallower gas fountains.

The quantity of methane hidden in gas hydrates in Baikal is estimated at one trillion cubic metres.

2. THE YAMAL CRATERS

Huge explosions in the past decade or so have caused the formation of at least 20 giant craters in and near the Yamal peninsula in northern Siberia. By summer 2021 scientists have identified some 7,185 bulging Arctic mounds, potentially at risk of erupting.

'Five to six per cent of these 7,185 mounds are really dangerous,' warned Professor Vasily Bogoyavlensky.

Gas fields at Bovanenkovo, Novoportovskoye and South-Tambey are in jeopardy, as is the strategic $27 billion Sabetta LNG hub, he said.

Some of these rapidly-developing potentially explosive bulging hillocks on the Yamal and Gydan peninsulas are close to settlements and gas fields vital for energy supplies in Europe.

Inside the ‘heave mounds’ is unstable methane released due to thawing permafrost.

One example was a summer 2020 eruption leaving a 40 metre (131ft) deep crater.

In an explosion in 2018 in Lake Otkrytie, its 1.5 metre (5ft) thick ice cover was smashed with debris scattering some 50 metres (165ft) from the epicentre.

3. WONKY RAILWAYS, TWISTED ROADS, COLLAPSING BUILDINGS

Some 65 per cent of Russia - the world’s largest geographical country - is permafrost, and it is thawing fast. Our pictures show some of the dire consequences, and the crisis will worsen in coming years.

Reports have warned of a dramatic weakening of the ‘bearing capacity’ of the ground inn, for example, Russia's diamond capital Yakutsk and nickel mining hub Norilsk, both built on permafrost.

Once usable railway lines built in the Stalin era in far-flung Siberian locations like TransBaikal are now wonky and twisted due to the ground moving because of permafrost thaw. Bridges, too, have collapsed.

Russia has used a trusted method of building in permafrost regions, driving piles deep into the frozen ground. But if the ground is no longer frozen, the whole reality changes. Swamps and lakes appear, towns and even cities become unviable.

Nikita Zimov, director of the Russian North-Eastern Scientific Station near Chersky has highlighted the destruction within two years of a defunct sewage treatment plant in Yakutia, the world's coldest inhabited region. It 'snapped in the middle' as a portion of the structure subsided, while a concrete road leading to the plant sank into a new ravine, totally vanishing, he said.

He warned: ‘The temperature of the permafrost is rising, and we are reaching the point when it will begin to thaw everywhere, and very actively. We are heading towards a vicious circle when climate warming will speed up the thawing of permafrost, which will in turn add to faster climate warming and further accelerate the thawing, until all active carbon is released from permafrost.’

From his vantage point running The Pleistocene Park, which aims to restore fauna of mammoth steppes of the Pleistocene Era, he envisages a terrible toll.

Permafrost is thawing much faster than many expected.

‘Once our permafrost starts to thaw we will no longer need to worry about factories or any other sources of emission, because the main emission of methane will be coming from here (in the Arctic). And the process has started.’

This devastating release will happen in a flash of the evolutionary timescale.

‘We believe this process will take from 100 or 200 years,’ Nikita Zimov said.

His concern relates to the top 40 metres (130 ft) layer of ground which is thawing ‘worryingly fast’ in Yakutia.

Permafrost is the hard frozen mix of soil, sand and ice lying under cities, towns and vast unpopulated areas in polar regions. Comprising up to 500 gigaton of organic matter like roots of ancient grass, bushes and trees, plus the remains of animals - this is permafrost in Yakutia alone, and by its estimated weight it is heavier than all currently growing Earth's biomass.

It is the world’s biggest reservoir of organic carbon which converts into a greenhouse gas including methane once it thaws.

4. THE MOUTH OF HELL IS OPENING WIDER

A new satellite image shows the widening of the Batagai Depression, a ‘megaslump’, nicknamed by the local residents as the Mouth of Hell. The tadpole-shaped giant hole was measured several years ago at 100 metres (330ft) deep and around 1,000 metres (3,300ft) in length, with a width of 800 metres (2,650ft).

New precise measurements are awaited from this gash in the ground but the snapshot from space shows it broadening. Inside the crater, as our pictures show, water frozen in the soil for tens of thousands of years trickles and gushes away, released from its ancient clasp.

Chunks of thawing permafrost fall off the cliffs.

Sergey Fyodorov, researcher at the Institute of Applied Ecology, Yakutsk, told us: 'One of the most serious things we must understand looking at this slump is that its growth is not something we, humans, can stop. We cannot put a curtain against the sun rays to stop it from thawing.

'Even at the beginning of September, when air temperatures drop to zero, you see springs and rivers of water.

'As you stand inside the slump on soft piles of soil that was left after ice thawed, you hear it 'talking to you', with the cracking sound of ice and a non-stop monotonous gurgling of little springs and rivers of water."

The trigger for his crater’s formation was man made, caused by the removal of trees.

Then the thawing of the permafrost in Yakutia took over, and the expansion is now rapid.

5. THE UNLOCKING OF ZOMBIE DISEASES

Annual discoveries are now made of the remains of extinct woolly mammoths or rhinos as well as long-gone cave bears and pre-historic horses. The thawing of permafrost has given scientists access to an untold treasure trove of not merely bones but the flesh and fur, the cells and even blood, of the past.

Scientists are working to bring some of these species back to life, yet there is another side to the reappearance of these lost animals.

In the last five years, born-again anthrax in the Yamal peninsula has been released and killed both humans and reindeer.

Hundreds of Russian chemical and bio-warfare troops were deployed to destroy the infected reindeer remains on Yamal. The release of eradicated smallpox remains a threat.

Siberia’s stark warning to Scotland for Cop26: climate change in the planet’s last great wilderness

A graveyard on the Kolyma River was created in the 1890s to bury the dead from a major smallpox outbreak. The combination of permafrost thawing and flooding - another consequence of climate change - risks reopening such graves.

Many other dangers lurk in shallow Arctic graves of both humans and animals, which might be unlocked from the ice after centuries, or longer.

Viktor Maleyev, deputy chief of Russia's Central Research Institute of Epidemiology, has warned of new "giant viruses" in, for example, woolly mammoths, the carcasses of which are now appearing with regularity.

‘Their pathology has not been proven, we must continue to study them,’ he said. ‘Climate change will bring us many surprises. I don't want to scare anyone, but we should be ready.’

A study released in October 2021 found that the bacteria Acinetobacter lwoffii, extracted from permafrost thousands or millions of years old, were resistant to antibiotics.

The bacteria were from the mists of time yet had much in common with modern strains, said scientist Dr Nikolai Ravin, head of the Laboratory of Molecular Cloning at the Research Centre of Biotechnology, Russian Academy of Sciences.

‘Our colleagues received similar results and the situation is frightening,’ he warned. ‘Global warming can only be slowed down, but it can never be stopped, and it can release new infections.

‘A study of these potential pathogens now buried in permafrost could save our lives and health in the future.’

6. WILDFIRES BURNING ALL YEAR, PEAT FIRES ACTIVE EVEN IN MINUS 60C COLD

In 2021 have seen the worst wildfires in recorded history. If this year, they were further south, last year they raged more intensively in the far north, above the Arctic Circle.

The statistics are jaw-dropping, and the consequences for Siberia’s nature, and residents, distressing. The phenomenon of ‘smoking snow’ in the Tomponsky district of Yakutia highlights the new normal.

Here a fire burns underground in the thawed permafrost, all year, even when the temperature plunges below minus 50C.

A video shows the wafts of smoke rising from the zombie fire some 400 km (250 miles) north-east of the republic’s capital Yakutsk, the world’s coldest city..

Local resident Ivan Zakharov, who filmed the fire at exactly minus 50C in January this year, told The Siberian Times: ‘It is burning in the same area that was hit by summer wildfires.

‘This area suffered extremely hot and dry weather. It must be either peat on fire here, or, as some hunters who noticed these fires suggest, possibly young coal (lignite).’

This year’s worst-ever wildfires were signalled in the first days of May - with snow and ice still on the ground - in the vicinity of Oymyakon, known as the world’s coldest permanently inhabited village.

Huge flames raged on the Road of Bones, built in the Soviet era by prisoners of repression in some of the world’s coldest outposts.

Yakutsk and other Siberian cities were blotted out by toxic fumes from the fires, as much as 95 times allowable levels, and the smoke which also wafted across the Pacific to North America.

The Siberian fires in 2021 exceeded those in the rest of the world combined, in a year that saw the huge infernos in the US, Spain and Turkey.

The destruction covered an area larger than Portugal, or Maine.

‘They have pumped 800 million tonnes of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere since the start of June, more than the annual emissions of Germany, Europe's biggest polluter,’ reported The Times.

‘One of the individual blazes was said by Greenpeace to be a contender for the planet's largest fire since records began.’

7. FLOODS... AND DROUGHTS

Children watched in horror as a bridge collapsed in severe floods in Trans-Baikal region in July. A truck was washed away by the swollen waters in Uryum but the driver miraculously escaped.

Siberia can experience floods and droughts at the same time, a weather rollercoaster of lashing rains but also lengthy parched periods without precipitation.

On the same day across the eight time zones from the Urals to the Pacific, weather and news reports may be drawing attention to record heat waves, burst rivers, dry spells, unseasonal snow and tornadoes.

The year 2019 saw the worst flooding in recorded history in Irkutsk region. An epicentre was Tulun where grandmother Anella Danelyuk, 83, called her family to say sudden surging water was up to her neck, as she claimed on a chest of drawers.

She made clear this was her final call before expecting to drown - and she was one of dozens to die and go missing as rivers rose by up to 14 metres (46ft).

Yet it is also long periods of drought - this year in the north - that has enabled the wildfires to rampage across Siberia.

8. NORTHERN SEA ROUTE

There was an epic sight last year of the giant sailing ship STS Sedov sailing across the Arctic Ocean from Asia to Europe. The crew encountered almost no significant ice floes across thousands of nautical miles.

An accompanying Russian icebreaker vessel was virtually redundant as the Sedov ventured across the Bering, Chukchi, East Siberian, Laptev and Kara seas.

The four-masted German-made steel barque’s journey shows that the Northern Sea Route now viably connects the Pacific and Atlantic.

How different from 142 years earlier.

The vessel sailed past the location off Chukotka where in 1878 the famous Vega Expedition became stuck in pack ice for 11 months as it made the first-ever successful voyage from Europe to Asia via the Arctic sea route.

Ivan Fedyushin, second officer on the STS Sedov, said: 'We did not encounter even remnants of ice fields. We can say that global climate changes now make sea routes in polar waters more accessible for all types of ships.'

This is an economic boon to Russia, and the coming years are expected to see a major rise in trade taking advantage of the northern route.

A new Nature survey shows a majority of the world’s leading climate scientists expect “catastrophic” impacts in their lifetimes driven by rising greenhouse gas emissions. Brilliant researchers, they’re just like you and me—but with more data, which actually makes the new survey even more unnerving.

The feature from Nature, published on Monday, involved querying Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change researchers. These are the same folks who put out a major report earlier this year warning that this is essentially the most consequential decade in human history, one that will play a major role in deciding just how severe global warming will be for generations to come. In other words, they’re deep in it.

Nature heard back from 92 of the 233 living IPCC authors. The results show that six in 10 of the respondents expect the planet to warm at least 5.4 degrees Fahrenheit (3 degrees Celsius), a level that’s well beyond the Paris Agreement target of 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit). And it’s double the 1.5-degree-Celsius (2.7-degree-Fahrenheit) target that policymakers and researchers (including the IPCC) have identified as a relatively safe level of heating that would allow small islands to remain above sea level and protect millions from food insecurity and violence. Just 20% of the researchers, meanwhile, expect the world to meet the Paris Agreement 2-degree-Celsius target, and a paltry 4% think 1.5 degrees Celsius is in play.

Even more upsetting, 88% of the researchers expect climate change to unleash catastrophic impacts in their lifetimes. Of course, you could argue that’s already happening. Research has shown climate change is playing a role in making heat waves, wildfires, and cyclones worse. To take one example, the Pacific Northwest heat wave this summer that was dubbed a “mass casualty event” was made 150 times more likely due to burning fossil fuels. It went from being a 1-in-150,000-year event in the pre-industrial era to a 1-in-1,000 year event in our current climate. And with each passing year of rising emissions, the odds of more extreme heat like it will rise.

The survey also shows that many scientists are struggling with grief and anxiety. Paola Arias, a climate scientist at Colombia’s University of Antioquia, told Nature that the climate crisis made her decide not to have children. Now, I should note that the Nature analysis is not a peer-reviewed study, and the response rate means there could be 141 happy-go-lucky scientists out there who are so sure the world will tackle climate change that they didn’t bother responding. But the results that mirror a peer-reviewed study of kids published in September, as well as anecdotal findings from those who have lived through climate disasters. Basically, those closest to the issue are feeling the most acute anguish.

This pessimism that the world will address climate change adds a new wrinkle to the discussion around just how we’re supposed to “feel” about the current state of the world. The topline findings in the Nature piece definitely lean toward the more doomer end of the spectrum, putting forward the idea that world leaders are simply incapable of getting their act together. Mouhamadou Bamba Sylla, an IPCC scientist from Senegal who is based at the African Institute for Mathematical Sciences in Rwanda, told Nature his home country has put together a bunch of plans to deal with climate change but that not much is being done to implement them.

The feature published as United Nations climate talks get underway in Glasgow. It certainly adds another layer of cynicism about just how much the talks will accomplish, particularly with key leaders skipping the event. But the failures scientists are worried about don’t stop them from acting. Two-thirds said they engage in advocacy on their own time, and 81% said they believe other scientists should, too. It reflects something more nuanced than the “we’re all going to die and should accept it” mentality that’s prevalent in the doomer world. Instead, it’s one grounded in the scientific reality that every ton of carbon pollution that doesn’t end up in the atmosphere is one worth fighting for. A world that’s 5.4 degrees Fahrenheit hotter is scary. But fighting for our future, even in the face of overwhelming odds, is better than doing nothing.

The food we eat is one of the leading sources of the toxic ambient fine particulate matter PM2.5, leading to over 890,000 premature death per year, according to a new study examining air pollution released through the global food supply chain.

The study by the University of Minnesota, looked into emissions across five stages of food production: pre-production (land-use change, fertilizer production) production (on-farm energy use, manure management, grazing, fertilizer use agricultural waste burning) post-production (food industry, retail), distribution, and waste.

Most PM2.5 emissions are generated by the energy and transport sectors, by burning fossil fuels which release pollutants in the air. However, the agriculture sector has its own share of such pollutants: the research found the global food system is a significant contributor to total anthropogenic emissions of primary PM2.5 (58%), ammonia (72%), nitrogen oxides (13%), sulfur dioxide (9%), and all other organic compounds released which do not include methane (19%).

Exposure to air pollution is the world’s leading environmental (health) risk factor for mortality. According to the WHO, air pollution kills an estimate of 7 million people worldwide every year, where 4.2 million of death are linked to exposure to PM2.5. Reducing air pollution can improve public health and well-being while reducing greenhouse gases that contribute to climate change.

“Food systems pose a wicked problem. We pointed out the paradigm of "eating enough and eating right": it is of utmost importance to meet the food demands of a growing population, but we also need to meet it with the least environmental damage,” said Srinidhi Balasubramanian, lead author of the study while carrying her Postdoctoral Research at the University of Minnesota now Assistant Professor in the Environmental Science and Engineering Department at the Indian Institute of Technology di Bombay.

By reviewing more than 4746 peer-reviewed English language publications from the past decade, the researchers found land-use change, livestock and crop production, and agricultural waste burning produces the highest amount of PM2.5 and directly affect human health. Agricultural production emissions deriving from energy use in farms and fertilizers use were dominant in North America and Europe. In Asia, Africa, and South America, land-use change from forest to feedstock and crop production, manure management, and agricultural waste burning were the primary contributors to PM2.5 emissions, particularly in Brasil, Angola, Indonesia and Thailand.

Research indicated that the number of premature deaths yearly might be even higher than the 890,000 calculated, as air pollution regulations in several countries often do not include the emissions accounting within the agricultural sector: “We identify gaps in emissions data and air quality predictions as a major limitation in our understanding of the air quality impacts of the global food system.” Emissions from agriculture-driven land-use change and livestock in Africa, as an example, are poorly constrained in comparison to the United States and Europe,” continued Balasubramanian.

Little is reported as well on ammonia emissions, which is heavily featured within fertilizers, and has a key role in the formation of ambient PM2.5.

Accelerating climate action in all different production stages of the agricultural sector will be vital to decrease air pollution, but without measuring emissions, countries might be unable to identify effective mitigation strategies that could reduce pollution.

Countries their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), the non-binding plans set by national governments defining their intensions with regards to climate change-related actions, offer some examples of how a focus on air pollution can increase climate change mitigation ambition and ultimately tackle food supply chain emissions.

Most companies in the agriculture sector suggest technological solutions can help reduce greenhouse gas emissions, proposing climate-smart and sustainable intensification of agriculture to curb emissions.

“Focusing on technological improvements cannot address the core problem and will only delay and deepen the engulfed climate, environmental, health, food and nutrition security crises,” says Lasse Bruun, CEO of 50by40, a global coalition of more than 70 organisations dedicated to cutting the global production and consumption of animal products by 50% by 2040.

Technological developments were found to be only a complementary mitigation practice (link to 10%) whereas reducing intensive farming practices, such as limiting fertilizers use, remains the most effective way for the food supply chain to meet global emission reduction targets.

Livestock farming and industry, which contribute to increasing PM2.5 emissions through land-use, will also need a deep transformation: “A just livestock transition can accelerate equitable food distribution, improve public health and the environment, and result in beneficial socio-economic benefits,” continued Bruun.

Increased commitments from stakeholders along the whole food supply chain will be key to tackle emissions: lowering nitrogen oxides and sulfur dioxide emissions within food retail, distribution and transportation could be mitigated by shifting away from fossil fuels towards cleaner and energy-efficient technologies.

Currently, over one third of food worldwide is lost or wasted along the supply chain. New food waste management practices as well as a reduction of food production could help decrease ammonia emissions released by the decomposition of organic waste at landfill sites, which enters the air we breathe.

The COP26 international climate-change negotiations have just begun in Glasgow, Scotland, and the vibes are … ambivalent. The leaders of Russia and China haven’t bothered to attend, but did promise to help end deforestation by 2030—though many observers are skeptical that they will keep their word. In the United States, President Joe Biden’s “Build Back Better” plan lost a powerful provision that would have helped convert the nation’s electricity grid to renewable energy, but still includes an unprecedented $555 billion to combat climate change.

In a prelude to the conference, the UN added up the most recent pledges of parties to the 2015 Paris Agreement. If all 192 keep their promises, the synthesis found, the planet would still be on track to warm 2.7 degrees Celsius, or 4.9 degrees Fahrenheit, by the end of the century. This is nearly twice the 1.5-degree-Celsius (2.7 Fahrenheit) goal agreed to in principle in Paris. But it is also not nearly the jump predicted in the hottest scenario envisioned in the latest report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change—4.4 degrees Celsius, or 8 degrees Fahrenheit.

The world is wandering into a kind of gray area between total failure and real global commitment to containing global warming. In a recent video call to supporters, Varshini Prakash, the head of the Sunrise Movement, which advocates for aggressive action on climate change, said she felt two ways at once—proud “that we forced Democrats and the president to care about our generation” and also angry.

“I feel disappointed that this is all that we’ve won,” she said.

It is hard to know how to feel. A future of possibly 5 degrees Fahrenheit of warming seems like an unknown country. Is it a civilization-ending crisis? Or is it a more familiar version of awful—a bit sweatier, more chaotic, and less just than the world we currently inhabit?

Brian O’Neill, the director of the Joint Global Change Research Institute, a partnership between the U.S. Department of Energy and the University of Maryland at College Park, has a clearer view of this question than most of us. He was one of the lead architects of the five different futures—called “shared socioeconomic pathways,” or SSPs—developed for the latest IPCC report.

These five futures aren’t just versions of 2100 at different temperatures. Each started with a different idea about how society might develop. The SSP 1 pathway, which keeps us under that 1.5-degree-Celsius goal, for example, is the “Sustainability” path. In this scenario, the global economy still expands, but humanity “shifts toward a broader emphasis on human well-being, even at the expense of somewhat slower economic growth over the longer term.” The highest-temperature scenarios are SSP 4, in which inequality accelerates to even more grotesque levels, but advanced technology zaps some emissions, and SSP 5, where the world simply charges forward with fossil-fuel-powered turbo-capitalism.

The path we seem to be on, at least for now, looks closer to SSP 2, which the authors call “Middle of the Road.” This is a world in which “social, economic, and technological trends do not shift markedly from historical patterns.” A world, in other words, in which we do not heroically rise to the occasion to fix things, but in which we also don’t get much worse than we already are.

So what does this SSP 2 world feel like? It depends, O’Neill told me, on who you are. One thing he wants to make very clear is that all the paths, even the hottest ones, show improvements in human well-being on average. IPCC scientists expect that average life expectancy will continue to rise, that poverty and hunger rates will continue to decline, and that average incomes will go up in every single plausible future, simply because they always have. “There isn’t, you know, like a Mad Max scenario among the SSPs,” O’Neill said. Climate change will ruin individual lives and kill individual people, and it may even drag down rates of improvement in human well-being, but on average, he said, “we’re generally in the climate-change field not talking about futures that are worse than today.”

But all the current physical impacts of climate change—drought, extreme heat, fire, storms, sea-level rise—would get significantly worse by 2100 under SSP 2. And say goodbye to coral reefs. “At 2.5 degrees [Celsius], it’s probably a world in which we don’t have them,” O’Neill said. “They don’t exist.” The Arctic? “My guess is that we would have a permanently ice-free Arctic in the summer. And so we would have all of the ecological consequences that would come along with that.”

All the IPCC scenarios might be wrong. They’re using statistical extrapolation and models, and as O’Neill reminded me, history is always wilder than people expect. (Just as Mad Max scenarios are missing from the SSPs, so are “no growth” scenarios.) But the world we are heading toward may be one in which the average human is living longer and making more money than ever, but some vulnerable humans and many nonhumans are collateral damage.

This is why many climate activists frame global warming as a problem of justice.

John Paul Jose is a young climate activist based in Kerala, India, where a series of flash floods linked to climate change have killed hundreds of people since 2018. “In all seasons throughout the year, there is cyclones, extreme rainfall and flood, heat waves,” he says. “And the place where I live is an ecologically fragile and sensitive hill, an extension of Western Ghats. The immediate danger we have is of landslides and flooding in low-lying areas. So anything could happen in future; the only thing is to live in fear and hope.” He wants to see drastic emissions cuts promised at COP26, along with serious money flowing from rich countries that have historically emitted the most toward poor communities where the impacts are the worst. At COP16, in 2010, wealthy nations promised to send $100 billion a year to “developing countries” by 2020, but Oxfam International estimates that climate-specific net assistance is currently more like $20 billion a year.

Climate advocates like Leah Stokes, a political scientist at UC Santa Barbara and an adviser to congressional Democrats on climate policy, are determined to find a way through this gray area. For her, the action that is happening is a motivation to push for even more action. “If they are able to pass this bill, it won’t just be okay; it will be transformative,” she told me. But there’s more to do after the celebrations. “The climate crisis is not going to be solved in one bill. Every ton matters. Every dollar we get invested in this matters. It all adds up,” she said.

Fighting for incremental investment dollars is not as dramatic as a single sweeping intervention to avoid total planetary ruin, and activists moved by horrific visions of human extinction may not be as motivated by the quest to steer the globe from SSP 2 to SSP 1, to shave just a few degrees off the total average warming. But anyone who needs an apocalypse to focus on can rest assured that it’s happening, unequally, for some. Even at today’s 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit) of warming, for many individual people, communities, and species, climate change has already meant the end of their world.

horrific visions of human extinction

Quote:horrific visions of human extinction

This is still silly.

Is just the (your quote) wording silly?

"This" is still silly.

The world is facing the prospect of a dramatic shortfall in food production as rising energy prices cascade through global agriculture, the CEO of Norwegian fertilizer giant Yara International says.

"I want to say this loud and clear right now, that we risk a very low crop in the next harvest," said Svein Tore Holsether, the CEO and president of the Oslo-based company. "We're going to have a food crisis."

Speaking to Fortune on the sidelines of the COP26 climate conference in Glasgow, Scotland, Holsether said that the sharp rise in energy prices this summer and autumn had already resulted in fertilizer prices roughly tripling.

In Europe, the natural gas benchmark hit an all-time high in September, with the price more than tripling from June to October alone. Yara is a major producer of ammonia, a key ingredient in synthetic fertilizer, which increases crop yields. The process of creating ammonia currently relies on hydropower or natural gas.

"To produce a ton of ammonia last summer was $110," said Holsether. "And now it's $1,000. So it's just incredible."

Food prices have also risen, meaning some farmers can afford more expensive fertilizer. But Holsether argues many smallholder farmers can't afford the higher costs, which will reduce what they can produce and diminish crop sizes. That in turn will hurt food security in vulnerable regions at a time when access to food is already under threat from the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change, including widespread drought.

The company, whose largest shareholder is the Norwegian government, has donated $25 million worth of fertilizer to vulnerable farmers, Holsether said. But Yara isn't able to eat the costs of such a dramatic rise in energy prices, he says. Since September, it has been curtailing its ammonia production by as much as 40% due to energy costs. Other major producers have done the same. Reducing ammonia production will decrease the supply of fertilizer and make it more expensive, undermining food production.

The delayed effects of the energy crisis on food security could mimic the chip shortage crisis, Holsether said.

"That's all linked to factories being shut down in March, April and May of last year and we're reaping the consequences of that now," he said. "But if we get the equivalent to the food system...not having food is not annoying, that's a matter of life or, or death."

Holsether pointed to efforts by the director of the UN World Food Program David Beasley, the former governor of South Carolina, to raise $6 billion in aid to combat preventable famine by directly targeting outspoken billionaires, including Elon Musk, for donations to the program.

Last week, Beasley called out Musk and Jeff Bezos, who appeared at COP26 on Tuesday, arguing that they could pony up the funds if they wanted to and barely feel the difference. In response, Musk tweeted that he was willing to sell $6 billion in Tesla stock if the World Food Program could explain "exactly" how that money would end world hunger.

Food scarcity is already reach desperate levels in many regions. On Wednesday, Frédérica Andriamanantena, the World Food Program's Madagascar program manager, appeared on a COP26 panel to describe the severity of the country's drought and resulting famine. Andriamanantena, who is from Madagascar, said drought had this year reduced the harvest to one-third of the average of the last five years. Where families had once had comfortable meals, children are now subsisting on foraged plants and cactus leaves.

"That is where the situation is now," she said.