Obviously, referring to the opening of the Seven Days Battles as "suicidal" is tendentious. However, i think that this first great operational effort on Lee's part shows all of his flaws--glaringly.

Stuart's "Ride Around McClellan" (it was so celebrated from the very beginning) was a case of Lee having failed to adequately impress upon a subordinate what his orders were, and how they were expected to have been carried out. It was not simply in the character of the orders, which are sufficiently ambiguous, but that Lee did not take the opportunity to impress upon Stuart what was expected of him, and to deny to him his plan of a glorious exploit when Stuart first proposed it to Lee, when they discussed the mission face-to-face. And nothing was said to Stuart upon his return about the three-ring circus which he had made of a crucially important reconnaissance. In fact, as the commander of the cavalry for the army, a good argument could be made that Stuart had no business to have lead the reconnaissance, or to have been absent from his command for several days. One might reasonably suggest that this would loom larger a year later, when Stuart "went missing" on the eve of the battle of Gettysburg.

Lee had the character of a loving and forgiving father (which he was in reality with his own family, whom he loved and who loved him deeply and genuinely), and not at all the character of a stern disciplinarian. His courtly manners, although he could and often was silent and reserved, tended to quickly convince people that he was "accessible," and kindly. Wherever he established his headquarters, civilians not only felt the could "come to call," but began to consider it their right. At Orange Court House, two matrons of the community called upon him, to complain that young ladies had "consorted" with the enemy by attending evening entertainments (grandiloquently referred to as balls) when the Federal forces had occupied the area. Lee replied that he thought it a good thing that the young ladies should find harmless entertainment in that manner, and then commented to the effect that he knew Major Sedgwick, and knew that he would have no one but gentlemen around him. I do not suggest that he ought to have adopted a severe attitude toward young ladies who wished to dance, even though with Federal officers--i do question why such things were so routinely brought to the attention of the man who commanded the Confederacy's largest army; this is something else which a competent staff does, they shield the commander from needless distractions.

(Another interesting, and perhaps significant matter arises here. Lee referred to Major General John Sedgewick as "Major Sedgwick," and this was not an isolated incident, either. During the battle of Chancellorsville, a chaplain rode into the clearing where Lee's "headquarters" [such as it was, and it was never much] was located, and almost breathlessly informed him that the Federals were pressing upon Jubal Early's line dangerously [Early was at Fredericksburg holding off the threat to Lee's rear]. Lee offered the good chaplain a glass of buttermilk, bad him sit down, and then commented that he was just sending Major General McLaws to call upon Major Sedgwick [Lafayette McLaws, was a division commander in the first corps of Lee's army; and this was the same Major General Sedgwick referred to above]. Note the punctilio with which he assures that he refers to McLaws by his correct rank, but refers to Sedgwick as "Major." Lee routinely referred to Federal officers--when he could bring himself to speak of the at all, he usually just said "those people," or "those people over there"--by their pre-war rank, by their rank in "the Old Army." Even more revealing is this:

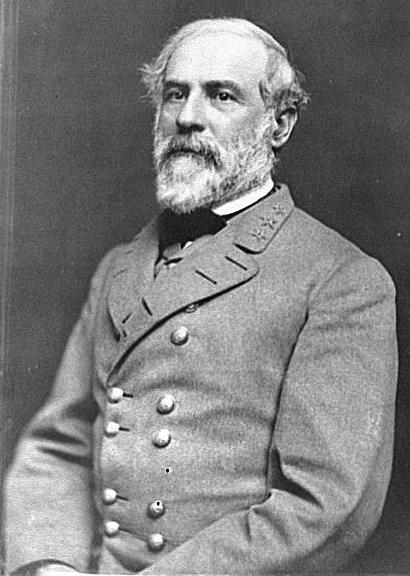

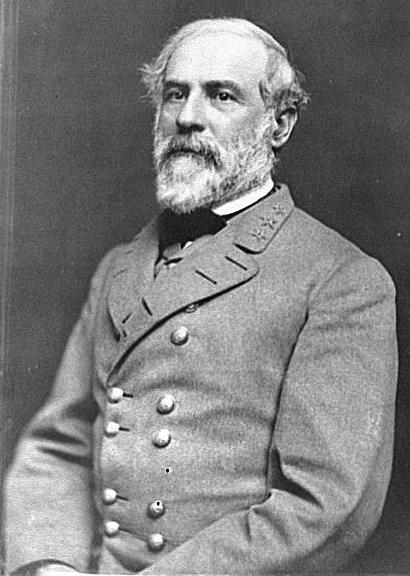

Note the rank insignia on Lee's uniform coat. He wears three stars--this is the rank insignia in Confederate service of a Colonel, which is the highest rank which Lee attained in the "Old Army" before he resigned. That, combined with frequent references to Federal officers whom he had known personally before the war by their pre-war rank is, to put it charitably, a little odd. During the Battle of the Wilderness, at the opening of the 1864 campaign, it appears that Lee might have briefly contemplated "suicide by combat" when he attempted to ride to the front at the head of the Texas brigade, at which time NCOs of the brigade were obliged to physically restrain him, amid anguished cries of "Lee to the rear!" I can't say it for a fact, but i am personally convinced that the war at least slightly unhinged him. He had spent 36 years in "the Old Army" when he resigned his commission, and he was a genuinely modest and unassuming man who never gloried in the slaughter and strife of war. It is reported by several witnesses that at the bloody slaughter of Federal troops at Fredericksburg in December, 1862, he said: "It is well that war is so terrible, lest we grow too fond of it." This is, of course, purely speculation, and Lee was a sufficiently "close" man, that we know little for a fact about how he felt about the war, and about his role in it.)

The opening of the Seven Days shows again that the greatest flaw as a commander of a large formation was Lee's failure to discipline his higher ranking officers properly. Jackson was arrived with his Valley Army, much later than had been planned (which is not a criticism of Jackson, who had performed a wonder of military organization and logistics to have brought his army so far, intact and ready to fight, in such a brief period of time). The plan called for him to attack Porter on his right flank and rear (to the north and east), triggering a series of echelon attacks as Jackson's advance cleared the bridges over the Chickahominy. Tired of waiting for the sound of Jackson's guns, Alvin Powell "Little Powell" Hill launched an attack on Porter which drew in Longstreet and Daniel Harvey Hill, in what became known as the Battle of Mechanicsville (where Hill crossed the river), or Beaver Dam Creek, where Confederate troops suffered a terrible slaughter to little tactical purpose. This was, however, an event which deepened McClellan's panic. He already believed Pinkerton's claptrap about 200,000 Confederate troops in Richmond, and the arrival of two "demi-divisions" to the south of the Richmond defenses convinced him that he was facing even more troops. His only response was to send more and more urgent orders to Porter to withdraw. Porter was already doing this, and he had already sent off his trains, after issuing ammunition and rations to his troops. His trains crossed the Grapevine Bridge at White Oak Swamp the same evening, and Porter began his withdrawal. He conducted a brilliant defense, and there is nothing harder in military operations than to conduct a fighting retreat while keeping your troops in hand and preventing a route. Attacked at Beaver Dam Creek and Boatswain's Swamp, Porter sent troops to his right, where he had not (yet) been attacked, correctly surmising that the intended plan called for an attack on his flank and rear.

But that attack never came. Jackson was to have made contact with W. H. C. Whiting's "demi-division," which was to have marched southeast, keeping it's right flank on the Chickahominy River. Jackson was to have conformed, and so arrived in large force (nearly as large as Porter's "Grand Division") on Porter's flank. As has been noted, Porter was not unprepared for such an eventuality.

Johnston had organized his army into demi-divisions, each of two brigades. When the Army of Northern Virginia was reorganized after the Seven Days, there were three divisions of five brigades, five divisions of four brigades, and Little Powell Hill's monster division of six brigades, the so-called Light Division. At the time of this first campaign of Lee, the Confederate command was "top-heavy," with a herd of general officers commanding small formations, and indulging in petty infighting due to their respective vanities. Lee was to greatly reduce the list of Major Generals with command responsibilities in his army, and to gradual weed out those he found lacking. After the Battle of Sharpsburg, or Antietam, offices to command divisions and Corps were found within the army, and their places were filled by promotions of serving officers who had distinguished themselves in the army. This is a reasonable policy, and might have been more efficient, if Lee had been able to handle his general officers more effectively.

Jackson did not make contact with Whiting, however, and despite the sound of furious battle, when he reached (as he thought) the position to which he had been ordered for the first day, he sent his troops into bivouac. Lee said nothing to Jackson, to Whiting or to Little Powell Hill about this after the campaign. He and his army and his lieutenants were wildly lionized by the Southern press and public after this campaign, so one might tend to excuse this--but Lee was ruthless about getting rid of "dead wood," and officers such as Magruder, Whiting and Huger were left out of the reorganization; nevertheless, he made no criticisms public or private of the actions or inaction of those who had "failed" him, but whom he intended to keep in service in his army. In the case of Magruder, this was injustice--Magruder, with a demi-division of a few thousand men, repeated his performance before Williamsburg, and marched them around rattling his sabre, and completely fooled McClellan about the defenses of Richmond, confirming what McClellan wanted to believe, that he was badly outnumbered. Magruder's major sin was that he could not be the friend of James Longstreet, which doomed any hope of a career in Lee's army. Lee may have found dealing with personalities distasteful, but he was not above playing the games himself.

It is not my intention to give detailed accounts of battles. It is my intention to ask why, and to provide my opinion on why, the battles fell out as they did. Jackson has been criticized, with a certain amount of justification, for being slow. In his defense, it can be pointed out that he had no maps, none of his staff was familiar with the region, Lee sent no staff officers to him, and his army had been campaigning and fighting from February of that year, four times traversing the length of the Shenandoah Valley, fighting in five major battles, and numerous small engagements, after which they marched from the Valley to Richmond, and were sent to fight five more battles. On the morning of the second day, a trooper who was familiar with the region was sent to Jackson by Stuart (both devout Christians and fierce fighters--a not incompatible circumstance--they were to become immediate and fast friends). One has to ask why it was that the commander of the army's cavalry was taking such an action on his own initiative, when the commander of the army ought to have provided maps, guides and staff officers to Jackson, whose role was crucial, and whose force, when combined with Whiting, represented about 40% of Lee's army. One has to ask why Lee did nothing to restrain Little Powell Hill when he attacked without orders, in contradiction of his orders, on the first day, and drew about 20% of the army into a futile and bloody battle. Not only did Hill not suffer the implied rebuke which Magruder, Huger and Whiting suffered in the army's reorganization, he was given the largest division in the army when it was reformed. Lee's failure to provide the most basic of staff services continued throughout the battles of the Seven Days. The trooper whom Stuart had sent to Jackson had been told that he was to lead Jackson to Cold Harbor. He did so, and Jackson, almost in a fury, asked him why the enemy was not there, when he had been told that he would find Porter at New Cold Harbor. The trooper lost his own temper (an incredible thing to do when dealing with Jackson), and pointed out that he had lead him to Cold Harbor, and no one had told him to lead him to New Cold Harbor. (There were two Cold Harbors--Cold Harbor, also known as Old Cold Harbor, and New Cold Harbor.) Jackson's march had been delayed on the first day because he had tried to find Spring Green Church--and apparently, Lee was himself unaware that Spring Green Church was miles from Porter's position. That Jackson was receiving his instructions from Stuart, by way of a single enlisted man sent on Stuart's own initiative is a very bad comment on Lee's conception of staff work. What is even more problematic is that Lee had made his name in the Old Army, and learned the trade of battle by serving as Winfield Scott's chief of engineers in the march from Vera Cruz to Mexico City. It is not just inexcusable that Lee's staff work was poor, his staff work was non-existant.

Had Jackson come up as expected, and had Hill waiting for Jackson to engage before attacking, the slaughter would have been bad enough--Porter's men were dug in behind field fortifications behind creeks and swamps. As it was, Hill's attack cost many irreplaceable lives with the dubious result that McClellan panicked even more than he previously had. McClellan needed no encouragement to imagine monsters in the dark waiting to pounce on him. And the South badly needed the men thrown away not once, but three times in the campaign because the Confederate attacks were uncoordinated. It is true that Jackson was late, but i've pointed out that this could not really be helped. That he wandered around for four days, doing little of value to Lee's army, other than further spooking a badly spooked opponent speaks volumes about Lee's failure to do basic staff work. Lee's plan was to "bag" Porter. Had he delayed even another day, Porter would probably have been marching away before an attack was launched. It could be argued that Lee was justified in attempting to destroy Porter while he still had the chance, but Lee was unaware of Porter's orders or of McClellan's panic. And the lives lost in fighting to make Porter do what he was already ordered to do were too high a price to pay. Which brings us to my final criticism of Lee as an army commander.

Lee was profligate of the lives of his men. He did nothing to interfere with Hill's unauthorized and unwise attack on June 26. This despite having said before witnesses that he was surprised to hear Hill's guns, and wondering what Hill thought he was doing. A Prussian observer who was assigned to Lee's army asked him a few months later what his method was. Lee replied that he brought his officers and troops to the place at which he wished to fight the enemy, and then he considered that he had done the whole of his duty. He said, in effect, that at that point, it was in God's hands. Lee was long supported by competent, and even brilliant lieutenants, but he often failed so often to meet even the low standard which he described to the young Prussian officer. The Seven Days was planned by the principle officers discussing Lee's plan on the evening of June 23, and that, apparently, assured Lee that he had done "the whole of [his] duty." It was to cost his army many lives which the Confederacy could ill afford.

The final debacle of the Seven Days the "battle" of Malvern Hill. Lee's plan had been to bag and destroy Porter. But there Porter was, on that low hill, with the survivors of his "grand division," Supported by more than 100 canon and more than half of McClellan's army. One futile attack after another was launched. Almost every Confederate gun battery which attempted to unlimber and fire was swept away by the concentrated Federal artillery before they could fire a shot. Those which managed to unlimber unheeded were destroyed within minutes of opening fire. Daniel Harvey Hill commented after the battle: "It wasn't war, it was murder." Lee can, in the most charitable construction, be said to have had too great a faith in the invincibility of his infantry. Tragically, those troops returned that confidence by a devotion which approached the suicidal.

Therefore, my criticism of Lee is that he was not effective in managing and disciplining his higher ranking lieutenants; that his staff work was not poor, it was not done at all; and that he would spend the lives of his men heedlessly, and quixotically, they loved him for it. I don't wish here to apply these criticisms to a discussion of his subsequent career, although i am prepared to do so. My next victim will be Grant, who comes off a little better.

The most i can say in Lee's defense is that the South expected it's heroes to stand on the defensive, but to attack savagely whenever the enemy invaded Southern territory--and one might say that Lee understood this better than any other man, except perhaps Joe Johnston, who refused to play the game. Johnston's biggest failing was that he saw how futile it all was, and rather than attacking, stood on the defense and punished the enemy bitterly for his attacks. That would not wash with the Southern public, and especially with Jefferson Davis, himself a graduate of the USMA, and a distinguished veteran of the Mexican War. Lee seems to have been the only other soldier whom Davis genuinely respected, and to whom he was willing to defer. Lee became a hero of the South as much because of his image as a bold and fearless cavalier (over the corpses of the Army of Northern Virginia) as for any technical skills, about which most people know little to nothing when witnessing a war from afar.

Lee's greatest strength was that in campaigning he was decisive and stood not upon the order of their going. Just before the battle of Cold Harbor in 1864 (right back where they started), Grant rode into the front yard of a justice of the peace east of Richmond. That man, being the gentleman he likely claimed to be, offered them such refreshment as was available to him, but was ignored by Grant. He reported that Grant took out his watch and commented to his staff: "If i don't hear the old fox's guns in fifteen minutes, i've got him." Five minutes later, the cannons began to roar at Old Cold Harbor. The Old Fox (as Grant habitually named him), had stolen another march on the Yankees.