"How would you get a cleanup crew on site with no port or airstrip?" asked Sergy. " We just don't have the infrastructure. It all boils down to a logistical nightmare."

Global warming

Kristin Grotting is a physiotherapist, who moved here 12 years ago.

The children's heavy clothes can leave them with mobility problems

Her naturally light complexion has been reddened by the constant summer sunlight.

The Arctic day lasts from March until October but it never gets very warm and, on the day we met, Kristin kept her thick coat zipped tight.

Looking out towards Longyearbyen bay, she explained that the Icefjord - as it is known - has stopped being icy.

Even in midwinter, the water no longer freezes and the glaciers around it are receding.

"We used to be able to take our snowmobiles right across that fjord," she told me. "Now we can't do that any more and we have to go the long way around."

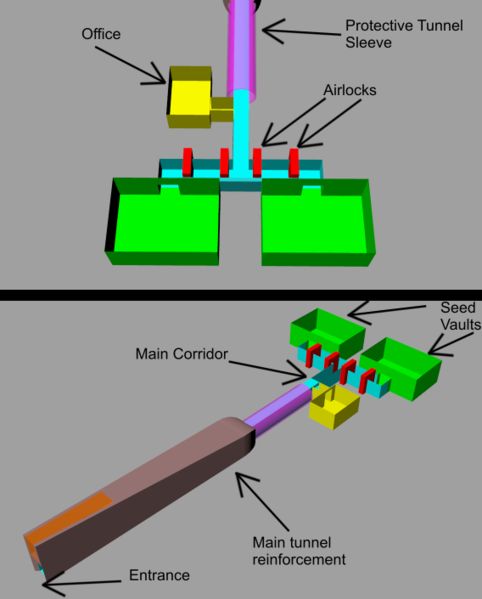

Very interesting news this one apparently, the Philippines (specifically the IRRI) has the distinction of being the largest contributor to the Norwegian-initiated Global Seed Vault, which is referred to by some media organizations as the "Doomsday Vault."

Global warming forces Russian scientists to abandon the ice

(By David Biello, Scientific American, July 14, 2008)

That's what happens when your lab sits on a melting ice floe. Adrift on ice in the Arctic Ocean, 21 Russian scientists (and two dogs) will need an early rescue thanks to global warming. The ice chunk supporting North Pole-35?-a project designed to study Arctic flora and fauna, environmental conditions and even geography?-has dwindled from 3 square miles to just 0.7 square miles.

That's still 2 million square feet, but it brings the floe's edge too close to the expedition's huts and equipment for comfort. So instead of abandoning the floe in September, as planned, scientists will climb aboard a research vessel towed by the nuclear ice-breaker Arktika in coming days. Just when depends on ice conditions, of course.

North Pole-35 is the 35th time Russian scientists have floated across the Arctic since 1937. On previous missions, they've helped define Russia's claims to Arctic territory, including the rich oil deposits believed to lie beneath the northernmost ocean. The current expedition started in September 2007, and most last at least a year.

The early rescue is yet another sign that the Arctic sea ice is rapidly disappearing. It worries climate scientists because the impacts of the North Pole melting are unknown. They could include changes in the amount of rainfall and snow across the northern hemisphere. Still, it is of a piece with U.S. ice experts' predictions that the Arctic could be ice-free as early as September of this year?- a situation unknown in recorded human history?-thanks to an early start to the melting season and a record retreat last year that left weaker ice in its wake. Russian scientists' ability to go with the floe in future may be in doubt.

"The observed rates of change have far outstripped what we projected," senior research scientist Mark Serreze of the U.S. National Snow and Ice Data Center told me last year. "We seem to melt a little more each summer."

International Polar Year

International Polar Year (IPY) 2007-2008 is an intensive burst of internationally coordinated, interdisciplinary, scientific research and observations focused on the polar regions. This initiative allows nations to make major advances in knowledge of the Arctic and Antarctic, including a greater understanding of how the rest of the world affects these vulnerable regions and how they in turn impact the rest of the world. Many key scientific questions remain beyond the capacity of individual nations and IPY provides the opportunity for countries to work cooperatively to advance the research.

IPY 2007-2008 is the first initiative of its kind in 50 years and is only the fourth such global scientific undertaking since the first in 1882. The last similar endeavour, held in 1957-1958 as part of the International Geophysical Year, paved the way for the space age with the launch of the world's first satellites and ultimately resulted in the signing of the Antarctic Treaty in 1961.

IPY 2007-2008 is the largest-ever international program of scientific research focused on the Earth's polar regions. It involves thousands of scientists from more than 60 nations, involved in more than 200 projects, examining a wide range of physical, biological and social research topics. For the first time, due in large part to Canada's leadership, IPY includes the human dimension of polar issues.

To do research in the Arctic, it is increasingly important for researchers to work closely with Canadian northern residents who know and understand the land and who may bring with them generations of traditional knowledge. All Canadian research projects had to meet strict criteria to promote Northern participation, including skills training to build long-term Northern research capacity and foster a new generation of Northern scientists.

IPY promises to provide a greater understanding of the physical, biological and social issues in the Arctic and Antarctic regions and to foster greater connections between Arctic residents, other Canadians and the rest of the world.

Study finds Arctic seabed afire with lava-spewing volcanoes

Margaret Munro

Canwest News Service

Wednesday, June 25, 2008

The Arctic seabed is as explosive geologically as it is politically judging by the "fountains" of gas and molten lava that have been blasting out of underwater volcanoes near the North Pole.

"Explosive volatile discharge has clearly been a widespread, and ongoing, process," according to an international team that sent unmanned probes to the strange fiery world beneath the Arctic ice.

They returned with images and data showing that red-hot magma has been rising from deep inside the earth and blown the tops off dozens of submarine volcanoes, four kilometres below the ice. "Jets or fountains of material were probably blasted one, maybe even two, kilometres up into the water," says geophysicist Robert Sohn of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, who led the expedition.

He and his colleagues, who describe the underwater scene in the journal Nature today, estimate that exploding mixtures of lava and gas flew out of the volcanoes at speeds of more than 500 metres a second. When the material hit the frigid seawater, Sohn says it would have formed huge clouds that rained volcanic material down on the sea floor, creating the carpet of glassy shards and bits that can be seen for kilometres.

The team explored the volcanoes last summer as the Russians were planting a flag on the nearby sea floor triggering an international flap over ownership of the seabed.

Sohn said in an interview Wednesday that his crew of 30 researchers from the U.S., Europe and Japan chuckled over the "grandstanding" as the Russians rumbled by in their icebreakers. But they stayed focused on the intriguing spot on the Gakkel Ridge they had come to explore. The 1,800-kilometre-long ridge, which cuts across the Arctic from Greenland to Siberia, is in international waters. It is one of the planet's "spreading" ridges where molten rock rises up from inside the earth creating new crust.

The $5-million expedition was financed by the U.S. National Science Foundation and NASA, which hopes to use the know-how gained in its hunt for extraterrestrial life. The scientists sent three unmanned probes down through the ice to explore a 30-kilometre-long stretch of the ridge where a swarm of undersea earthquakes occurred in 1999.

The probes, one of which "flew" just two to five metres above the sea floor, gathered samples and images that point to remarkable under sea eruptions. In the valley where the two crustal plates are coming apart, which is about 12 kilometres across, they found dozens of distinctive flat-topped volcanoes that appear to have erupted in 1999, producing the layer of dark, smoky volcanic glass on the seabed.

"The scale and magnitude of the explosive activity that we're seeing here dwarfs anything we've seen on other mid-ocean ridges," says Sohn, who studies ridges around the world. The volume of gas and lava that appears to have blasted out of the Gakkel volcanoes is "much, much higher" than that seen at other ridges.

Sohn says it would have been "spectacular to witness" the eruptions, but he says it is a good thing there is four kilometres of seawater on top of the Gakkel Ridge as the eruptions would have been "highly problematic" had they occurred on dry land.

The scientists say the heat released by the explosions is not contributing to the melting of the Arctic ice, but Sohn says the huge volumes of CO2 gas that belched out of the undersea volcanoes likely contributed to rising concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. How much, he couldn't say.

There are no volcanoes exploding in the area right now, but they scientists say there appears to still be a lot happening on the sea floor. "I had the impression this whole central volcano area was oozing warm fluid," says Henrietta Edmonds of the University of Texas, who was on the expedition tracking the plumes of warm waters rising from the spreading ridge. She says they point to the presence of "gushing black smokers" as well as microbial and other forms of life that can thrive in scalding, mineral-rich waters that percolates out of spreading ridges.

The scientists say they have explored just one small stretch of the Gakkel Ridge and hope to return in a few years.

"This will be a gold mine for deep sea research for many, many, many years," says Sohn.

Medvedev Signs Law on Arctic Resources

(Coalition for Democracy in Russia, July 19th, 2008)

Russian President Dmitri Medvedev signed a law Friday which determines how the country's underwater Arctic resources will be tapped, Prime-Tass reports. The law, approved by the State Duma on July 4th and the Federation Council on July 11th, empowers the government to hand-pick companies to develop resource extraction on the continental shelf.

Vast reserves of oil and other mineral resources are thought to lie under Arctic waters, and may become more accessible as global warming continues. According to the new legislation, permits to develop plots of the continental shelf will be handed out directly by the government without auctions or tenders.

"The continental shelf is our national heritage," Medvedev said, most likely indicating that development of the Arctic will be left to Russian state-run companies.

Commenting on the cancellation of auctions in the Arctic development plan, Medvedev underscored that "This was done consciously to ensure rational use of this national wealth."

Russia has moved to assert control over underwater territory. In August 2007, Russian scientists led an underwater geological investigation that tested soil samples and determined that a mountain range in the Arctic Ocean could be considered Russian territory. The surrounding area is thought to contain some 25 percent of the world's undiscovered oil and gas resources. A later expedition found that the range was connected to the Russian continental shelf, and planted a Russian flag underneath the North Pole.

A recent report by European Union experts has suggested that Russia will clash with Europe over arctic resources in the near future. Analysts from the United States, meanwhile, testified before Congress that the US is falling behind Russia in the "Arctic race."

Wealth of oil in Arctic, report says

(but what will be the cost at the pump ?)

The Canadian Press

July 23, 2008 at 12:40 PM EDT

A new study suggests that the equivalent of 30 billion barrels of oil lie undiscovered underneath the sea ice and frigid waters of North America's Arctic.

The report by the U.S. Geological Service has for the first time put some hard numbers behind the energy potential of the North and could add new urgency to the debate over control of those resources.

Most of the oil and gas lies in waters that Canada shares with the United States and Denmark, and which are subject to boundary disputes.

Most of it also lies offshore, presenting energy companies with tough challenges in bringing it to market.

The survey suggests that there is the equivalent of 412 billion barrels of oil throughout the Arctic, most of it off the coast of Russia.

That is more than twice the 173 billion barrels of oil thought to lie in Alberta's oilsands.

Pieces are breaking off this thread, and floating away.

Cold Comfort: Arctic Is Oil Hot Spot

(By GUY CHAZAN, Wall Street Journal, July 24, 2008)

The Arctic contains just over a fifth of the world's undiscovered, recoverable oil and natural-gas resources, according to a review released Wednesday, confirming its potential as the final frontier for energy exploration.

A report by the U.S. Geological Survey found that the area north of the Arctic Circle has an estimated 1,670 trillion cubic feet of natural gas -- nearly two-thirds the proved gas reserves of the entire Middle East -- and 90 billion barrels of oil.

The report, the culmination of four years of study, is one of the most ambitious attempts to assess the Arctic's petroleum potential. One of its main findings is that natural gas is three times as abundant as oil in the Arctic, and most of that gas is concentrated in Russia.

The survey reflects interest in an area once off-limits to oil exploration. It has become more accessible as global warming reduces the polar icecap, opening valuable new shipping routes, oil fields and mineral deposits.

But any attempt to create an Arctic drilling frenzy will likely meet strong resistance from environmentalists worried about the impact on what is still a near-pristine wilderness. And it could trigger a flurry of territorial disputes over who controls the oil and gas under the Arctic seabed.

The USGS report, which brings together disparate data held by individual countries as well as new information from geologists working in the field, is the first time anyone has produced a comprehensive, publicly available estimate of the Arctic's hydrocarbon treasures.

Its conclusions will be read closely at a time when concerns about supply have driven up crude prices. But scientists cautioned that it will take decades to develop the Arctic's hard-to-get-at oil and natural gas.

"It will not ratchet up global production like a new Saudi Arabia," said Donald Lee Gautier, a USGS geologist who played a key role in the survey, known as the Circum-Arctic Resource Appraisal. "These are additions that will come over time."

Exploration in the area north of the Arctic Circle has already unearthed more than 400 oil and gas fields. They account for about 40 billion barrels of oil and more than 1,100 trillion cubic feet of gas, the USGS said.

But large parts of the Arctic, especially offshore, remain unexplored. Near-permanent sea ice makes it almost impossible to acquire seismic data and drill exploratory wells.

Climate change is opening the region. The Northwest Passage, home to deadly ice floes that can crush ships, was ice-free last summer. Some predict it will turn into a new trade route between Europe and Asia, and a channel that oil companies can use to ferry workers, equipment and supplies around more freely.

Enticed by the promise of vast deposits, energy companies are flocking northward -- often because they have few other places left to go. The Arctic, especially offshore Alaska and northern Canada, is one of the few parts of the world where the majors can easily acquire exploration acreage. Elsewhere, soaring crude prices have prompted oil-rich states to renegotiate contracts and sometimes kick out Western oil companies.

Earlier this year, Royal Dutch Shell PLC spent more than $2 billion acquiring drilling leases in Alaska's Chukchi Sea. Last year, Exxon Mobil Corp. and Imperial Oil Ltd. of Canada bid nearly $600 million to win a big exploration block in Canada's Beaufort Sea. BP PLC will spend $1.5 billion to develop Liberty, an oil field off the northern coast of Alaska.

Yet drilling in the Arctic is controversial. Shell has been forced to delay a drilling plan off northern Alaska because of a legal challenge from environmental groups that say it could harm whale and walrus populations.

Oil exploration might also be hampered by rising nationalism. The five circumpolar states -- Canada, Russia, the U.S., Norway and Denmark -- are scrambling to claim new territory in the central Arctic Ocean. Last August, a Russian submarine planted the country's flag on the seabed some 14,000 feet under the North Pole. Shortly afterward, Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper announced that his country's military presence in the Arctic would be beefed up.

The rhetoric stems from disagreements over who has sovereignty over the North Pole. Russia rests its claim on the theory that two underwater mountain chains that cross the Arctic Ocean, the Lomonosov and Mendeleev Ridges, are in fact extensions of its continental shelf. Denmark disputes that. A United Nations body that rules on such claims has recommended additional research.

Mr. Gautier, the U.S. geologist, said that one of the survey's main conclusions was that a lot of the gas in the Arctic is in Russian waters, in places like the South Kara Sea and South Barents Basin. These are both geological extensions of onshore areas that are rich in gas.

The presence of so many hydrocarbons there "will reinforce Russia's global dominance in natural-gas resources," he said. Russia is already the largest producer of natural gas and sits on the biggest gas reserves.

Yet there is little likelihood that much of Russia's Arctic wealth will be exploited any time soon. The country still has vast untapped fields onshore that are first in line to be developed.

Development would also be hampered by Russia's likely reluctance to let in foreign companies with experience developing oil and gas riches in hostile environments like the Arctic. Some firms have been allowed in, but only as junior partners of state-controlled Russian entities such as OAO Gazprom.

The situation could change. Neil McMahon, an oil analyst at Sanford Bernstein, said Russia will come under mounting pressure to sell offshore leases to Western companies and use the cash to boost investment in flagging domestic oil production.

Ice Free

(By STEPHAN FARIS, New York Times, July 27, 2008)

Greenland's ice sheet represents one of global warming's most disturbing threats. The vast expanses of glaciers ?- massed, on average, 1.6 miles deep ?- contain enough water to raise sea levels worldwide by 23 feet. Should they melt or otherwise slip into the ocean, they would flood coastal capitals, submerge tropical islands and generally redraw the world's atlases. The infusion of fresh water could slow or shut down the ocean's currents, plunging Europe into bitter winter.

Yet for the residents of the frozen island, the early stages of climate change promise more good, in at least one important sense, than bad. A Danish protectorate since 1721, Greenland has long sought to cut its ties with its colonizer. But while proponents of complete independence face little opposition at home or in Copenhagen, they haven't been able to overcome one crucial calculation: the country depends on Danish assistance for more than 40 percent of its gross domestic product. "The independence wish has always been there," says Aleqa Hammond, Greenland's minister for finance and foreign affairs. "The reason we have never realized it is because of the economics."

Climate change has the power to unsettle boundaries and shake up geopolitics, usually for the worse. In June, the tiny South Pacific nation of Kiribati announced that rising sea levels were making its lands uninhabitable and asked for help in evacuating its population. Bangladesh, low-lying, crowded and desperately impoverished, is watching the waves as well; a one-yard rise would flood a seventh of its territory. But while most of the world sees only peril in the island's meltwater, Greenland's independence movement has explicitly tied its fortunes to the warming of the globe.

The island's ice cover has already begun to disappear. "Changes in the ocean eat the ice sheet from underneath," says Sarah Das, a glaciologist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts. "Warmer water causes the glaciers to calve and melt back more quickly." Hunters who use the frozen surface of the winter ocean for hunting and travel have found themselves idle when the ice fails to form. The whales, seals and birds they hunt have begun to shift their migratory patterns. "The traditional culture will be hard hit," says Jesper Madsen, director of the department of Arctic environment at the University of Aarhus in Denmark. "But from an overall perspective, it will have a positive effect." Greenland's fishermen are applauding the return of warm-water cod. Shops in the island's capital have suddenly begun to offer locally produced potatoes and broccoli ?- crops unimaginable a few years earlier.

But the real promise lies in what may be found under the ice. Near the town of Uummannaq, about halfway up Greenland's coast, retreating glaciers have uncovered pockets of lead and zinc. Gold and diamond prospectors have flooded the island's south. Alcoa is preparing to build a large aluminum smelter. The island's minerals are becoming more accessible even as global commodity prices are soaring. And with more than 80 percent of the land currently iced over, the hope is that the island has just begun to reveal its riches.

Offshore, where the Arctic Ocean is rapidly thawing, expectations are even higher. The U.S. Geological Survey estimates that Greenland's northeastern waters could contain 31 billion barrels of undiscovered oil and gas. On the other side of the island, the waters separating it from Canada could yield billions of barrels more. And while Greenland is still considered an oil exploration frontier, Exxon Mobil, Chevron, Canada's Husky Energy and Cairn Energy and Sweden's PA Resources are aleady ramping up exploration.

In November, Greenlanders will vote on a referendum that would leverage global warming into a path to independence. The island's 56,000 predominantly Inuit residents have enjoyed limited home rule since 1978. The proposed plan for self-rule, drafted in partnership with Copenhagen, is expected to pass overwhelmingly. It would grant the first $16 million of oil and mineral income to the local government, with further revenues split equally until Denmark's share reaches roughly the $680 million a year Greenlanders currently receive from the Danes. Then there would be no further obstacles to sovereignty. "When we reach the point where we no longer need the subsidy, we'll be able to say we're economically independent," Hammond says. "There will be nothing that ties us anymore."

mctag wrote :

Quote:Pieces are breaking off this thread, and floating away.

"McTag : COME BACK HERE AT ONCE !!!"

McTAG : "i'll come back when i'm good and ready !

..............hold it ... there is a crevice ! "

CRASH !

Map tries to sort out Arctic mess

(Randy Boswell, Canwest News Service, August 06, 2008)

British researchers have unveiled a new map of the Arctic Ocean and its jurisdictional disputes - a resource they're billing as the "most precise depiction yet" of the geopolitical hot spot and as a remedy for the confusion and conflict they say has marked the so-called "new Cold War" in recent months.

The map - prompted by the global uproar over last summer's Russian flag-planting on the North Pole sea floor - was produced by experts at the International Boundaries Research Unit at Durham University and shows "the current state of play in the region" by outlining existing territorial rights, current areas of dispute and possible overlapping seabed claims by Canada, Russia, Denmark (Greenland), Norway and the U.S. (Alaska) under provisions of the UN Convention on the Law the Sea.

"We hadn't seen anybody attempt to produce an accurate map," geographer Martin Pratt, the IBRU's research director, told Canwest News Service Tuesday. "Hopefully it's a map that allows policy-makers and politicians and anyone interested in these jurisdictional issues to have a more informed discussion of the areas that are at stake."

He added that because of the environmental challenges facing the rapidly melting polar region and the vast potential for Arctic oil and gas development, the world needs to have "a bit of visual clarity" about competing claims and interests.

Among the contentious areas highlighted on the map is 6,250-sq.-km section of the Beaufort Sea that both Canada and the U.S. consider theirs.

Russia and Denmark are each shown asserting potential claims over the North Pole itself, but IBRU research director Martin Pratt said the projection was based on prevailing trends in maritime boundary demarcation and "does not rule out the possibility of Canada making a claim to the North Pole, as well."

Meanwhile, the disputed Northwest Passage - the fabled sea route that passes through Canada's Arctic islands - is shown on the map as part of Canada's internal waters rather than as the international strait that the U.S. and other countries argue it is.

Hans Island - the contentious rock that lies midway between Ellesmere Island and Greenland, and the source of a high-profile diplomatic tussle between Canada and Denmark in 2005 - was considered too insignificant in terms of boundary issues and "didn't make the cut," said Pratt.

"While there are a number of disagreements over maritime jurisdiction in the Arctic region - and potential for more as states define the areas over which they have exclusive rights over the resources of the continental shelf more than 200 nautical miles from their coastal baselines - so far all of the Arctic states have followed the rules and procedures for establishing seabed jurisdiction," the IBRU stated in releasing its new map.

The map's creation is another sign of the growing global interest in how the potential petroleum resources of an increasingly accessible Arctic are distributed between Canada and the four other nations with Arctic Ocean coastlines.

The U.S. government's geological service recently issued an updated assessment of the polar region's potential oil and gas resources, which are now pegged at about one-quarter of the world's entire reserves.

Meanwhile, the Arctic is experiencing another significant thaw this summer after last year's record-setting meltdown, which opened the Northwest Passage more completely than ever before.

Last week, Canadian scientists reported that a chunk of the 3,000-year-old Ward Hunt Ice Shelf broke off into the sea north of Ellesmere Island, and a Baffin Island park was largely closed to tourists after unprecedented melting and erosion sparked fears of flash flooding.

Pacific species set to invade warmer Arctic, Atlantic waters

Ice-free conditions to cause reopening of migration route

Randy Boswell

Canwest News Service

Friday, August 08, 2008

A new United States study says Canada should brace for an invasion of Pacific Ocean species along its Arctic and Atlantic coasts as warmer waters and ice-free conditions continue to transform the polar region and reopen a migration route for sea creatures that has been closed for more than three million years.

Just as last year's record melt along the Northwest Passage stoked renewed interest in trans-Arctic shipping, marine animals in the North Pacific are likely to begin moving into and across the unlocked Arctic Ocean to the North Atlantic, say University of California marine ecologist Geerat Vermeij and California Academy of Sciences paleontologist Peter Roopnarine in an article to be published today in the magazine Science.

The study, titled The Coming Arctic Invasion, says that, along with the "poleward expansion" of some southern species -- highlighted recently in Canada by reports of grizzly bears encroaching on polar bear habitat -- "an even more dramatic inter-oceanic invasion will ensue in the Arctic: North Pacific lineages will resume spreading through the Bering Strait into a warmer Arctic Ocean and eventually into the temperate North Atlantic."

The researchers say a similar trans-Arctic migration occurred about 3.5 million years ago, when a warm period created favourable feeding conditions for hundreds of different marine creatures that moved eastward from the Bering Sea to colonize the Arctic and eventually the Atlantic Ocean.

The proof, the authors state, is found in fossil records of various Pacific mollusk species in Greenland. However, that window of warmth soon closed and "sea-ice expansion in the coastal Arctic Ocean ended trans-Arctic dispersals."

Now, citing the recent trend of rapid Arctic ice loss and predictions of "perennially ice-free conditions" along the Alaskan and northern Canadian coasts by 2050 or earlier, the scientists say Pacific species of mussels, barnacles, snails and whelks "are likely to respond to these future conditions" by moving east toward the Atlantic.

The result, they say, is that "these trans-Arctic invaders of the future will likely enrich Atlantic biotas" rather than causing a wave of extinctions.

"The composition and dynamics of north Atlantic communities will change," Mr. Roopnarine says in a summary of the study. "But whether that will help or harm local fisheries is an open question. Humans may have to adapt as well."

Asked about whether the same mechanism could drive fish and mammals from Pacific to Arctic to Atlantic, Mr. Roopnarine said yesterday that the warming "could definitely promote invasions by other aquatic species, fish included."

He added that their study focused on marine mollusks because of the excellent fossil record documenting their existence during the warming of 3.5 million years ago.

He also said that Canada's northern coast and Arctic islands were likely to be a key passageway for migrating creatures "since most of these species are relatively shallow-dwelling coastal species. Ultimately, however, that depends on future patterns of ice loss or retreat."

© The Ottawa Citizen 2008

Canada, US team up in key Arctic study

(Agence France-Presse, August 11, 2008)

OTTAWA (AFP) ?- Canada and the United States will join forces to gather scientific data on the Arctic continental shelf, in a step aimed in part at bolstering claims over the potentially oil-rich zone, Ottawa and Washington have announced.

Minister of Natural Resources Gary Lunn said on Monday Canada and the United States will conduct a joint survey of the undersea polar continental shelf in the western Arctic beginning next month.

The Canadian Coast Guard icebreaker Louis S. St.-Laurent will rendezvous with the US Coast Guard Healy in the Beaufort Sea, north of Canada and Alaska, on or about September 8 for the three-week joint operation.

"Through collaboration with our US neighbors, we will maximize both scientific and financial resources while collecting important data as part of Canada's submission to the UN by 2013," Lunn said in a statement.

Canada has until the end of that year to submit data on the extent of its continental shelf to the United Nations.

The study was announced just days after Canadian representatives presented findings from a joint Canadian-Danish survey in the eastern Arctic as part of Ottawa's intent to extend Canada's territory beyond the current 200 nautical miles (370 kilometers).

Last week Lunn said the Canadian-Danish research determined the undersea Lomonosov Ridge is attached to the North American and Greenland plates, directly challenging a Russian claim to a vast portion of the Arctic.

The extension could add up to 1.75 million square kilometers (676,000 square miles) -- an area three times the size of France -- to Canada's claims in the contested region, according to Lunn.

The Healy will be charged with mapping the seafloor while the Louis S. St. Laurent will work to determine the thickness of sediment, in a collaboration that will "assist both countries in defining the continental shelf in the Arctic Ocean," according to a US State Department statement.

Five countries that border the Arctic Ocean -- Canada, Denmark, Norway, Russia and the United States -- dispute the sovereignty of the region's waters.

The US Geological Survey believes that the Arctic region contains 90 billion barrels of oil waiting to be explored.

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) stipulates that any coastal state can claim territory 200 nautical miles from their shoreline and exploit the natural resources within that zone.

Interest in the economic exploitation of the Arctic has increased significantly in recent years as melting ice floes have eased access to the region's rich oil and gas reserves.