Methane concentrations in the atmosphere raced past 1,900 parts per billion last year, nearly triple preindustrial levels, according to data released in January by the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Scientists says the grim milestone underscores the importance of a pledge made at last year’s COP26 climate summit to curb emissions of methane, a greenhouse gas at least 28 times as potent as CO2.

The growth of methane emissions slowed around the turn of the millennium, but began a rapid and mysterious uptick around 2007. The spike has caused many researchers to worry that global warming is creating a feedback mechanism that will cause ever more methane to be released, making it even harder to rein in rising temperatures.

“Methane levels are growing dangerously fast,” says Euan Nisbet, an Earth scientist at Royal Holloway, University of London, in Egham, UK. The emissions, which seem to have accelerated in the past few years, are a major threat to the world’s goal of limiting global warming to 1.5–2 °C over pre-industrial temperatures, he says.

Enigmatic patterns

For more than a decade, researchers have deployed aircraft, taken satellite measurements and run models in an effort to understand the drivers of the increase (see ‘A worrying trend’)1,2. Potential explanations range from the expanding exploitation of oil and natural gas and rising emissions from landfill to growing livestock herds and increasing activity by microbes in wetlands3.

“The causes of the methane trends have indeed proved rather enigmatic,” says Alex Turner, an atmospheric chemist at the University of Washington in Seattle. And despite a flurry of research, Turner says he is yet to see any conclusive answers emerge.

One clue is in the isotopic signature of methane molecules. The majority of carbon is carbon-12, but methane molecules sometimes also contain the heavier isotope carbon-13. Methane generated by microbes — after they consume carbon in the mud of a wetland or in the gut of a cow, for instance — contains less 13C than does methane generated by heat and pressure inside Earth, which is released during fossil-fuel extraction.

Scientists have sought to understand the source of the mystery methane by comparing this knowledge about the production of the gas with what is observed in the atmosphere.

By studying methane trapped decades or centuries ago in ice cores and accumulated snow, as well as gas in the atmosphere, they have been able to show that for two centuries after the start of the Industrial Revolution the proportion of methane containing 13C increased4. But since 2007, when methane levels began to rise more rapidly again, the proportion of methane containing 13C began to fall (see ‘The rise and fall of methane’). Some researchers believe that this suggests that much of the increase in the past 15 years might be due to microbial sources, rather than the extraction of fossil fuels.

Back to the source

“It’s a powerful signal,” says Xin Lan, an atmospheric scientist at NOAA’s Global Monitoring Laboratory in Boulder, Colorado, and it suggests that human activities alone are not responsible for the increase. Lan’s team has used the atmospheric 13C data to estimate that microbes are responsible for around 85% of the growth in emissions since 2007, with fossil-fuel extraction accounting for the remainder5.

The next — and most challenging — step is to try to pin down the relative contributions of microbes from various systems, such as natural wetlands or human-raised livestock and landfills. This may help determine whether warming itself is contributing to the increase, potentially via mechanisms such as increasing the productivity of tropical wetlands. To provide answers, Lan and her team are running atmospheric models to trace methane back to its source.

“Is warming feeding the warming? It’s an incredibly important question,” says Nisbet. “As yet, no answer, but it very much looks that way.”

Regardless of how this mystery plays out, humans are not off the hook. Based on their latest analysis of the isotopic trends, Lan’s team estimates that anthropogenic sources such as livestock, agricultural waste, landfill and fossil-fuel extraction accounted for about 62% of total methane emissions since from 2007 to 2016 (see ‘Where is methane coming from?’)

Global Methane Pledge

This means there is plenty that can be done to reduce emissions. Despite NOAA’s worrying numbers for 2021, scientists already have the knowledge to help governments take action, says Riley Duren, who leads Carbon Mapper, a non-profit consortium in Pasadena, California, that uses satellites to pinpoint the source of methane emissions.

Last month, for instance, Carbon Mapper and the Environmental Defense Fund, an advocacy group in New York City, released data revealing that 30 oil and gas facilities in the southwestern United States have collectively emitted about 100,000 tonnes of methane for at least the past three years, equivalent to the annual warming impact of half a million cars. These facilities could easily halt those emissions by preventing methane from leaking out, the groups argue.

At COP26 in Glasgow, UK, more than 100 countries signed the Global Methane Pledge to cut emissions by 30% from 2020 levels by 2030, and Duren says the emphasis must now be on action, including in low- and middle-income countries across the global south. “Tackling methane is probably the best opportunity we have to buy some time”, he says, to solve the much bigger challenge of reducing the world’s CO2 emissions.

Trend has developed over six EU elections between 1994 and 2019 and is more marked in colder climates

Matching extreme weather events to voting patterns has revealed that in Europe people who have experienced flooding, heatwaves and forest fires are more likely to vote green. This trend has developed over six European elections between 1994 and 2019, a period when climate change has gone from a theoretical threat to voters to many having experienced devastating events not previously seen in their lifetimes.

The realisation that urgent action is needed for climate mitigation and adaptation has led voters to support green party candidates. Greens have done better wherever the calamities have been worst. The trend is more marked in the north and west of the EU where the climate is more moderate and colder, presumably because extremes have become more noticeable.

The researchers noted that the tendency to vote green was enhanced where the population was generally fairly affluent and economic conditions were good. When the economic conditions worsened, this factor again assumed greater importance in voting choices.

The European elections are by proportional representation, so that minority parties, which the greens are in all of the 34 countries involved, will get some seats even if their overall vote is relatively small. Currently greens hold 69 seats out of 705 in the European parliament.

Sea levels along the coastal United States will rise by about a foot or more on average by 2050, government scientists said Tuesday, with the result that rising water now considered “nuisance flooding” will become far more damaging.

A report by researchers from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and other agencies also found that, at the current rate of warming, at least two feet of sea-level rise is expected by the end of the century.

[...]

The report said that the calculated rise over the next three decades means that floods related to tides and storm surges will be higher and reach farther inland, increasing the damage.

What the report described as moderate or typically damaging flooding will occur 10 times more often by 2050 than it does today. Major destructive coastal floods, although still relatively rare, will become more common as well.

For communities on the East and Gulf coasts, the expected sea level rise “will create a profound increase in the frequency of coastal flooding, even in the absence of storms or heavy rainfall,” said Nicole LeBoeuf, director of the National Ocean Service.

Most comprehensive scientific analysis to date finds words are not matched by actions

Accusations of greenwashing against major oil companies that claim to be in transition to clean energy are well-founded, according to the most comprehensive study to date.

The research, published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal, examined the records of ExxonMobil, Chevron, Shell and BP, which together are responsible for more than 10% of global carbon emissions since 1965. The researchers analysed data over the 12 years up to 2020 and concluded the company claims do not align with their actions, which include increasing rather than decreasing exploration.

The study found a sharp rise in mentions of “climate”, “low-carbon” and “transition” in annual reports in recent years, especially for Shell and BP, and increasing pledges of action in strategies. But concrete actions were rare and the researchers said: “Financial analysis reveals a continuing business model dependence on fossil fuels along with insignificant and opaque spending on clean energy.”

Numerous previous studies have shown there are already more reserves of oil and gas and more planned production than could be burned while keeping below the internationally agreed temperature target of 1.5C. In May 2021, the International Energy Agency (IEA) said there can be no new fossil fuel developments if the world is to reach net zero by 2050.

Oil companies are under increasing pressure from investors to align their businesses with climate targets. But their plans have faced scepticism, prompting the researchers to conduct the new research, which they said was objective and comprehensive.

“Until there is very concrete progress, we have every reason to be very sceptical about claims to be moving in a green direction,” said Prof Gregory Trencher, at Kyoto University in Japan, who worked with Mei Li and Jusen Asuka at Tohoku University.

“If they were moving away from fossil fuels we would expect to see, for example, declines in exploration activity, fossil fuel production, and sales and profit from fossil fuels,” he said. “But if anything, we find evidence of the reverse happening.”

“Recent pledges look very nice and they’re getting a lot of people excited, but we have to put these in the context of company history of actions,” Trencher said. “It’s like a very naughty schoolboy telling the teacher ‘I promise to do all my homework next week’, but the student has never worked hard.”

The new study, published in the journal PLOS One, found mentions of climate-related keywords in annual reports rose sharply from 2009 to 2020. For example, BP’s use of “climate change” went from 22 to 326 mentions.

But in terms of strategy and actions, the researchers found “the companies are pledging a transition to clean energy and setting targets more than they are making concrete actions”.

Chevron and ExxonMobil were “laggards” compared to Shell and BP, the researchers said, but even the European majors’ actions appeared to contradict their pledges. For example, BP and Shell pledged to reduce investments in fossil fuel extraction projects, but both increased their acreage for new exploration in recent years, the researchers said.

Furthermore, the analysis found Shell, BP, and Chevron increased fossil fuel production volumes over the study period. None of the companies directly releases data on their investments in clean energy, but information they provided to the Carbon Disclosure Project indicates low average levels ranging from 0.2% by ExxonMobil to 2.3% by BP of annual capital expenditure (capex). Separate analysis by the IEA indicates that investment in clean energy by oil and gas companies was about 1% of capex in 2020.

“Until actions and investment behaviour are brought into alignment with discourse, accusations of greenwashing appear well-founded,” the researchers said.

A spokesperson for ExxonMobil said: “The move to a lower emission future requires multiple solutions that can be implemented at scale. We plan to play a leading role in the energy transition, while retaining investment flexibility across a portfolio of evolving opportunities, including for example carbon capture, hydrogen and biofuels, to maximise shareholder returns.”

A Chevron spokesperson said: “We are focused on lowering the carbon intensity in our operations and seeking to grow lower carbon businesses along with our traditional business lines. We are planning $10bn in lower carbon investments by 2028.”

Shell’s spokesperson said: “Shell’s target is to become a net zero emissions energy business by 2050, in step with society. Our short, medium and long term intensity and absolute targets are consistent with the more ambitious 1.5C goal of the Paris Agreement. We were also the first energy company to submit its energy transition strategy to shareholders for a vote, securing strong endorsement.”

A spokesperson for BP said: “In 2020 BP set out our new net zero ambition, aims and strategy, and in 2021 completed the largest transformation of the company in our history to deliver these. Because this paper looks back historically over the period 2009-2020, we don’t believe it will take these developments and our progress fully into account.”

Trencher rejected the charge that the analysis was out of date: “We included the documents that were published during 2021, so the so-called data gap is only about six months and we don’t find any evidence of any new actions that would change any of our findings.”

“Unfortunately, the way the energy markets are structured around the world, fossil fuels still enjoy many [regulatory and tax] advantages and renewables are still disadvantaged,” he said.

Scientists working with one of the world’s largest climate research publishers say they’re increasingly alarmed that the company consults with the fossil fuel industry to help increase oil and gas drilling, the Guardian can reveal.

Elsevier, a Dutch company behind many renowned peer-reviewed scientific journals, including The Lancet and Global Environmental Change, is also one of the top publishers of books aimed at expanding fossil fuel production.

For more than a decade, the company has supported the energy industry’s efforts to optimize oil and gas extraction. It commissions authors, editors, and journal advisory board members who are current employees at top oil firms. Elsevier also markets some of its research portals and data services directly to the oil and gas industry to help “increase the odds of exploration success”.

Several former and current employees say that for the past year, dozens of workers have spoken out internally and at company-wide town halls to urge Elsevier to reconsider its relationship with the fossil fuel industry.

“When I first started, I heard a lot about the company’s climate commitments,” said a former Elsevier journal editor who agreed to speak on condition of anonymity. “Eventually I just realized it was all marketing, which is really upsetting because Elsevier has published all the research it needs to know exactly what to do if it wants to make a meaningful difference.”

What makes Elsevier’s ties to the fossil fuel industry particularly alarming to its critics is that it is one of a handful of companies that publish peer-reviewed climate research. Scientists and academics say they’re concerned that Elsevier’s conflicting business interests risk undermining their work.

Julia Steinberger, a social ecologist and ecological economist at the Université de Lausanne who has published studies in several Elsevier journals, said she was shocked to hear that the company took an active role in expanding fossil fuel extraction.

“Elsevier is the publisher of some of the most important journals in the environmental space,” she said. “They cannot claim ignorance of the facts of climate change and the urgent necessity to move away from fossil fuels.”

She added: “Their business model seems to be to profit from publishing climate and energy science, while disregarding the most basic fact of climate action: the urgent need to move away from fossil fuels.”

Elsevier and its parent company, RELX, say they are committed to supporting the fossil fuel industry as it transitions toward clean energy. And while Elsevier has emerged as an industry leader with its own climate pledges, a spokesperson for the company said they are not prepared to draw a line between the transition away from fossil fuels and the expansion of oil and gas extraction. She voiced concern about publishers boycotting or “canceling” oil and gas firms.

“We recognize that we are imperfect and we have to do more, but that shouldn’t negate all of the amazing work we have done over the past 15 years,” Márcia Balisciano, founding global head of corporate responsibility at RELX, told The Guardian.

Of the more than 2,000 scholarly journals that Elsevier publishes, only seven are specific to fossil fuel extraction (14 if you count special publications and subsidiaries). Those journals include Upstream Oil and Gas Technology, the editor-in-chief of which works for Shell, and Unconventional Resources, which is edited by a Chevron researcher. It also runs a subsidiary book publisher, Gulf Publishing, which includes titles such as The Shale Oil and Gas Handbook and Strategies for Optimizing Petroleum Exploration.

Two book cover images are shown side by side. The one on the left shows an illustration of an oil rig in a field with the title “Shale Oil and Gas Handbook: Theory, Technologies and Challenges”. The one on the right has the title text “Strategies for Optimizing Petroleum Exploration” in a maroon-colored box on a sage green background.

Two books published by Elsevier’s subsidiary, Gulf Publishing, which is entirely focused on the fossil fuel industry. Composite: Elsevier

Elsevier also provides consultancy services to corporate clients. For the past 12 years, it has marketed a tool called Geofacets to fossil fuel companies. Geofacets combines thousands of maps and studies to make it easier to find and access oil and gas reserves, in addition to locations for wind farms or carbon storage facilities.

The company claims the tool cuts research time by 50% and helps identify “riskier, more remote areas that had previously been inaccessible.”

Top climate scientists, including those published in Elsevier’s own journals, however, say just the opposite must happen in order to avert a climate catastrophe. Limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius or less requires a worldwide decrease in fossil fuel production with over 80 percent of all proven reserves being left in the ground.

“We will not comment on the practices of individual companies, but any actions actively supporting the expansion of fossil fuel development are indeed inconsistent” with the United Nations’ sustainable development goals, said Sherri Aldis, acting deputy director for the UN department of global communications.

RELX is an astoundingly profitable company, with annual revenues topping $9.8bn, about a third of which are brought in by Elsevier. Balisciano emphasizes that fossil fuel content represents less than 1 percent of Elsevier’s publishing revenue, and less than half of Geofacets’ revenue, which itself only represents around 2 percent of Elsevier’s earnings.

RELX and Elsevier say the bulk of their work supports and enables an energy transition via publications centered on clean energy. “We don’t want to draw a binary and we don’t think you can just flip a switch, but we have been reducing our involvement with fossil fuel activities while increasing the amount of research we publish on climate and clean energy,” said Esra Erkal, executive vice president of communications at Elsevier.

Elsevier is not alone in navigating relationships with both climate researchers and fossil fuel executives. Multiple other publishers of peer-reviewed climate research have signed on to the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals Publishers Compact while also partnering with the oil and gas industry in various ways.

An image shows the cover of an issue of The Lancet, with the title “The 2020 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change”. The cover image is a silhouette of a child standing on a dark path in a wooded area.

The Lancet, one of Elsevier’s top journals, publishes an annual report on how climate warming affects human health. Photograph: The Lancet

The UK-based publisher Taylor & Francis, for example, signed the UN pledge and released its own net-zero commitments while also touting its publishing partnership with “industry leader” ExxonMobil, the oil company most linked to obstructionism on climate in the public consciousness. Another top climate publisher, Wiley, is also signed onto the sustainability compact while publishing multiple books and journals aimed at helping the industry find and drill for more oil and gas.

“It’s problematic,” said Dr. Kimberly Nicholas, associate professor of sustainability science at Lund University in Sweden, noting that while corporate greenwashing is rampant across multiple industries, the publishers of peer-reviewed climate research have a unique responsibility.

“If the same publisher putting out the papers that show definitively we can’t burn any more fossil fuels and stay within this carbon budget is also helping the fossil fuel industry do just that, what does that do to the whole premise of validity around the climate research? That is what’s deeply concerning about these conflicts,” she said.

Ben Franta, a researcher at Stanford University who has also published studies in Elsevier journals, notes that the publisher’s relationship with oil firms is indicative of just how entwined that industry is with so many other aspects of society.

“This all happens without the broader public knowing, and it operates to entrench the industry,” he said. “To effect a rapid replacement of fossil fuels, I believe these entanglements will need to be exposed and reformed.”

Elsevier, for its part, emphasizes the role of editorial independence. “We wouldn’t want to tell journal editors what they can and can’t publish,” Balisciano said. However, such conflicts often place researchers in a tough position to navigate.

James Dyke, assistant director of the Global Systems Institute at the University of Exeter, was surprised that Elsevier would be working to contradict climate researchers in this way.

“It’s hard to believe that a company that publishes research about the dangers of the climate and ecological crises is the very same company that actively works with oil and gas companies to extract more fossil fuels, which drags us towards disaster,” he said.

Time to release the WOKE thought police and Inquisitors !!!!!

Scientists and academics say they’re concerned that Elsevier’s conflicting business interests risk undermining their work.

A rather self indulgent burst of closeminded, name-calling and intolerant prejudgment.

Time to release the WOKE thought police and Inquisitors !!!!!

Categorical prejudgments such as yours are the hallmark of oppressive intolerance; completely opposed to dispassionate scientific inquiry & study, and are deserving of the criticism I offered.

I first heard the standard joke about fusion as an undergraduate physics student in the 1960s: Fusion power is 50 years away—and probably always will be.

More than 50 years later, we still don't have fusion. That's because of the huge experimental challenges in recreating a miniature sun on earth.

Still, real progress is being made. This month, UK fusion researchers managed to double previous records of producing energy. Last year, American scientists came close to ignition, the tantalizing moment where fusion puts more energy out than it needs to start the reaction. And small, fast-moving fusion startups are making progress using different techniques.

A limitless, clean source of baseload power might be within reach—without the nuclear waste of traditional fission nuclear plants. That's good, right?

Not quite. While we're closer than ever to making commercial fusion viable, this new power source simply won't get here in time to do the heavy lifting of decarbonisation.

We are racing the clock to limit damage from climate change. Luckily, we already have the technologies we need to decarbonise.

How much progress is being made on fusion?

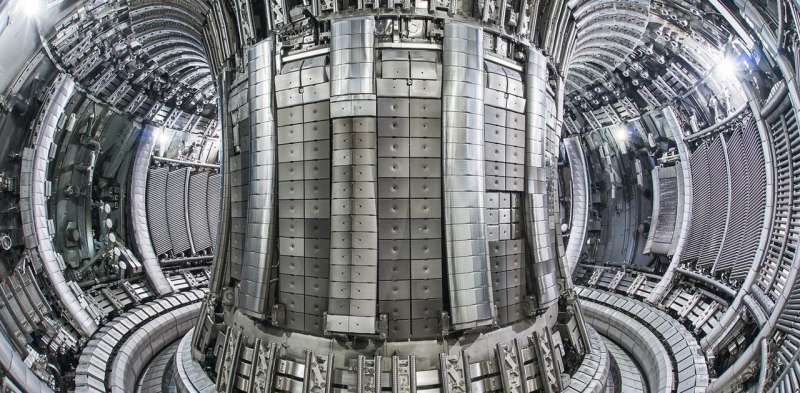

Five seconds. That's how long the UK's Joint European Torus was able to sustain a fusion reaction, producing enough energy to run a typical Australian household for about three days. That's a small fraction of the energy needed to make the fusion reaction happen, which used two 500 megawatt flywheels. That amount of power would meet the peak needs of 100,000 average Australian households. So we are still a long way from getting a net energy benefit from fusion.

On a technical front, achievements like this are incredible. Nuclear fusion is the process that powers stars like the sun, and we are working to harness this for our own use.

Solar, wind and storage - the new electricity model.

At very high temperatures, light atoms such as hydrogen can combine to produce another element such as helium, releasing enormous quantities of energy in the process.

In the sun, these fusion reactions take place at temperatures about 10 million degrees. We can't do it at that temperature, because we don't have access to the enormous gravitational pressure at the center of the sun.

To achieve fusion on earth, we need to go hotter. Much hotter. Experiments like the one in the UK are able to superheat a body of gas called a plasma to inconceivable temperatures, reaching as high as 150 million℃. The plasma has to be confined by incredibly strong magnetic fields and heated by powerful lasers.

This temperature is far hotter than anywhere else in our solar system—even the center of the sun.

While the recent progress represents a major step forward, sober reflection suggests the dream of limitless clean energy from hydrogen is still a long way off.

On the megaproject front, the next step is the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) being built in southern France. Far too big for any one country, this is a joint effort by countries including U.S., Russia, China, the UK and EU member countries.

The project is enormous, with a vessel ten times the size of the UK reactor and around 5,000 technical experts, scientists and engineers working on it. Famously, the project's largest magnet is strong enough to lift an aircraft carrier.

Even this enormous project is only expected to produce slightly more power than it uses—around 500 megawatts. The first experiments are expected by 2025.

To me, this illustrates how far away commercial fusion really is.

Construction of the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor megaproject seen from a drone as of October 2021.

Fusion won't get here in time

It will take decades yet to go from these promising experiments to a proven technology powering modern society. That means it simply will not get here in time to make a real contribution to slowing and reversing climate change.

To have a decent chance of keeping climate change below 2℃, we have to get to net zero emissions worldwide in under 30 years.

We can't wait. We have to decarbonise energy supply and energy use as quickly as possible.

Many countries are already moving at speed. The UK is planning to get to zero-emissions electricity within 12 years. States like South Australia and New South Wales should get there around the same time. The International Energy Agency predicts renewables will become the largest source of electricity generation worldwide by 2025.

The shift away from baseload

Even if fusion arrives, it would face major challenges due to the cost of the plants and the changing nature of the grid.

In the second half of the twentieth century, power stations became larger to achieve economies of scale. That worked, until recently. Only ten years ago, large coal-fired or nuclear power stations produced cheaper electricity than solar farms or wind turbines.

This picture has changed dramatically. In 2020, global average prices of power from new large wind turbines was 4.1 cents per kilowatt-hour, while solar farms were even cheaper at 3.7 c/kWh. The average for new coal? 11.2 c/kWh.

Fusion power is premised on the old baseload grid model, as seen in this EUROfusion diagram of a planned future fusion power plant.

Ever more favorable economics drove a massive investment in renewables in 2020: 127 gigawatts of new solar, 111 of new wind and 20 of hydro-power. By contrast, only 3GW of net nuclear power came online, while coal-fired power actually dropped.

As a result, we're seeing a global shift away from old models of baseload power, where power is generated in large power stations and transported to us by the grid.

These shifts are driven by cost. The price of electricity from renewables is now falling below the running costs of old coal-fired or nuclear power stations. Coal power requires digging the stuff up, transporting it, and burning it. Renewables get their power source delivered free of charge.

The idea of fusion power is alluring. There's a real appeal in the idea we could replace large coal and gas stations with one large clean fusion power plant. That, after all, is the selling point of the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor: to produce baseload power.

But will we need it? The pattern of power supply is changing. The massive take-up of solar power by households means we have now permanently shifted from the old model of large power stations to one where supply is distributed around the network.

It will be a technological marvel if we are finally able to build fusion plants in the second half of this century. It's just that they won't be in time.

Luckily for us, we don't need fusion. We already have what we need.

Limitless power arriving too late: Why fusion won't help us decarbonize

Solar, wind and storage - the new electricity model.

Protesters gathered in High Wycombe on Friday to implore their MP, Steve Baker, to quit as a trustee of the Global Warming Policy Foundation, a thinktank that has been accused of being one of the UK’s leading sources of climate scepticism.

Christians from the MP’s constituency prayed and sang Amazing Grace outside the constituency office, holding signs reading “Praying 4 Steve Baker”, “The Earth is what we all have in common”, “… And God created science”. Baker is an evangelical Christian.

Ruth Jarman, from Christian climate action group Operation Noah, led those assembled in prayer. She said: “I didn’t realise there was a connection between my faith and my environmentalism until I was in my 30s. I was walking down the street and suddenly remembered the first line of the Bible that states ‘in the beginning, God created the Earth.’

“We are knowingly trashing what God has made. That’s a hugely terrifying thought, really. I understand why some people have not made that connection, I’m here praying that Steve Baker makes that connection.”

As I said, there's nothing about "thought police" in the article. Your dumb comment got the criticism it deserved. If you had said something intelligent you might have gotten a response more to your liking.

Really, is "WOKE thought police and Inquisitors" your idea of "dispassionate scientific inquiry & study"? Sounds like juvenile name-calling to me.

And no, mouthing simplistic prescriptions for how we can prevent climate change while burning more fossil fuel is just the latest permutation of climate change denial.

I've watched you people subtly change your approach over the years as the evidence of warming has steadily increased. It's like the tobacco industry pushing low tar cigarettes.

(you mean Bjørn Lomborg)

My statement about managing the consequences while avoiding exaggerating the phenomenon and inflicting worse outcomes on humanity in ill-conceived preventive measures was simply a far more rational approach.