**

24

**

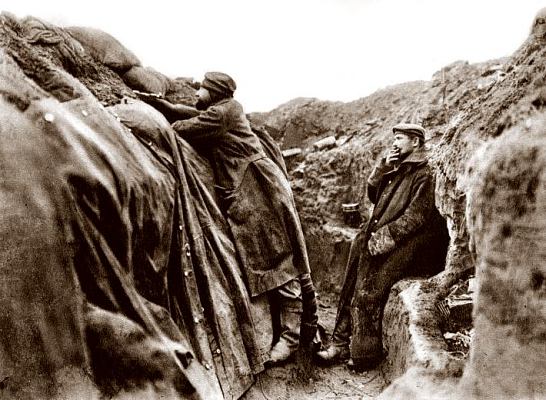

As day began to wane, so a sour mist crept up around us, clammy and foreboding. Fit for any graveyard.

Tom lay curled on the ground, the collar of my great coat turned up to partially hide his face.

His damaged eyes were closed, but I could hear him breathing.

During our excursion through no-man's-land, we'd come across an assortment of abandoned kit; including rifles, empty tins and water bottles, rotting haversacks

even a rugby jersey hung from a post. Odd, half completed scenes that sometimes included dead men and sometimes did not.

Despite that, (and rather unfortunately from where I sat shivering like a dog without my coat) I could see no likely looking scrap to use for a blanket against the coming night.

In every direction lay only banks and folds of mud, discarded wire and a small number of dead trees.

While light remained, I considered searching around in our immediate location for some shelter - or at very least, taking time to try and determine our position; but in the end I did not have the will to do either of those things - or anything at all, it seemed; only very, very carefully, lie back in the mud to watch the changing sky.

My wounds were sore and my muscles ached as if fed some wretched poison. Indeed, it hurt even to shiver

but shiver I did, as the cold snaked its way into my bones, and sunk its long fangs into the lacerations on my face, numbing them.

Until the thought of dying of exposure, seemed almost attractive.

Before my eyes a bank of clouds on the horizon swelled pomegranate-red, as the sun slipped further and further away, into the west.

How I wished I had the strength and indeed, the freedom to get up and follow its light far beyond this blasted horizon.

I imagined that death would be like walking into that vast sunset

away from this desperate place. Across bombed fields which would transform in rays of light, growing more and more to resemble the fields I grew up in - until eventually, finally, I would find my way home.

*

*

"Tom? Do you remember the night of the raid?"

"The raid?

Aye."

His voice sounded strong to my ears.

"It ain't a thing a man would be forgettin'."

"No. No, I suppose not."

It may surprise you to know that I was still interested in making conversation with Tom as I lay there watching the sun desert us, knowing it may well be the last time I was to ever look upon that fabulous star, but there it is

even when death feels close, the quiet seems to warrant polite conversation.

It was still light, but colour was fading slowly from the land and as shadows lengthened, so the bleak vista began to take on a strange, unfamiliar aspect. I wondered if we were already dead and this was hell.

Beside me, Tom sighed

"I 'ave ta say, Sir, I thought it were gona be an 'avoc raid

. not the sneaky type, like."

"Really?" I was intrigued.

"And you still volunteered?"

'Aye."

Havoc. He was talking about a fairly big squad of twenty-odd men with bags of bombs, hitting the German trench in a surprise attack, in the dead of night.

"I always fancied m'self as a marauder, like

. "

I could only presume he was joking.

The raiders were men willing to smash out brains and cut throats in the manner of assassins. Volunteers of course, carrying various trench weapons, (including hammers and knuckle-duster knives) creeping up on an unsuspecting enemy. Gaining ground by stealth initially, then letting loose - striking fast, with brutal force - killing or disabling as many men as possible, before blowing up the night and retreating under cover of smoke.

An

unofficial and bloody venture, thought up by our lot - to demoralise and unnerve Jerry.

Not to mention, waste a terrific amount of his ammunition.

A whole enemy line has been known to open up on retreating raiders, letting them have it with everything they can lay their hands on - including howitzers - sometimes hitting their own trenches in the confusion.

Corporal Jones (known to carry a bludgeon and knife for close combat) had been among those who made it back from a particularly hectic scrape just a month after Yates joined us on the line (and while we were still discovering the new Lieutenant's fervour for rules and regulations).

Jones' close pal, Ned Richards (a regular in the army before war broke out) had also been lucky that night.

"Tom."

"Aye."

"Do you ever think about Ned Richards?"

"Ned?

Aye."

I waited for him to say more, to perhaps share some amusing reminiscence (and there were bound to be plenty) - but he was asleep again - and I was alone with my thoughts.

*

*

"Ere

it sounds like Ned Richards made it."

" I bleedin' 'ope so

. we're 'alf way through a game o' cribbage and I'm winning."

"Just 'ope 'e can run faster'n 'e can peg."

"You men there

. get yourselves under cover."

"Right'o Sir."

"Sir? Thought you might like to know Corporal Jones just got back from the forward trench. Word 'as it, Ned Richards made it too. We 'aven't seen 'ide or 'air of 'im yet, though."

"Thank you, Blake. Any word on Lieutenant Price?"

"No Sir, but I 'eard there were loses from 'is platoon."

"I see. Alright. Get yourselves away

and dig in. I've a feeling Jerry's cranking up the big guns."

"Right'o, Sir."

I watch the men as they move without any particular haste, down the support trench to their cubby-holes.

Their mud niches.

There they will soon sit alone (or in twos) listening to the shells falling, huddled with scant protection, while the less expendable, at very least, enjoy the semblance of a shelter.

I intend paying a visit to Corporal Jones, but first I get up on the fire-plate and look between the bags. There is renewed activity in our front trenches.

A flare goes up, followed by another. Someone rattles out a few rounds on a Vickers gun.

Everyone is jumpy over on the edge of no-man's-land. In a way, I wish that I were forward with them, doing something useful.

I certainly cannot rest.

An hour before, I'd been woken from a warm, overdue sleep by Gregory and Yates, their voices filling the officer's shelter, their snappy discourse relentlessly nudging me back into consciousness.

For a while I had listened to their words, hoping they would fade out again; but they only grew sharper in the heat of their debate.

In the end, I had relented, getting up and into my boots without uttering a word, before leaving them to it.

Doing so without my coat now seems rather stupid and I regret my temper, as I stand shivering, looking out from my position - over empty ground and beyond the front trench towards the distant, dark pitch of no-man's-land. The bleak void stretches extensively across the low floor of the valley. I think about the German Cavalryman and wonder if he is out there somewhere, staring towards our lines from the darkness.

A sudden, wrenching feeling of homesickness hits me.

For a second or two I don't really care what happens here. I already know we shall all of us be losers at the end of this war.

Suddenly I want a hot soak it a deep bath and a proper shave in a mirror above a sink. I want the smell of honeysuckle growing outside an open window. To hear Mother calling to you and Michael from the kitchen door.

I long for sounds of normality.

Here on the British line we've been listening to the fireworks (courtesy of Lieutenant Price) for the hour.

First on the far side of no-man's-land, then gradually drawing closer. Now the Maxim guns have fallen quiet.

Men will be out spotting - watching for the enemy of course, who might decide on a surprise raid in the inevitable tit-for-tat (rather than leaving all the fun to the artillery) - but also they'll be looking for stragglers. Raiders who (for whatever reason) have been unable to complete the journey back, and now lie out there somewhere, hoping for rescue.

Any time soon, Jerry's artillery will begin its own ruckus.

Dawn is close.

*

*

Inside the NCO shelter, men have gathered around the seated Corporal Jones, whose giant frame casts a looming shadow on the clay wall behind him.

"Thought I'd bloody 'ad it this time

"

Jones is faintly trembling all through his body, but the clear eyes staring out through blacking, blood and splatters of mud, are calm enough.

His sheepskin waistcoat is foul; but it isn't his blood.

Apart from a few cuts across the forehead, he looks to be unscathed.

"Good to see you back in one piece, Corporal."

"Hello, Sir."

"As you are, Jones

As you were, all of you."

"Officer's shelter not bloody flooded again is it, Sir?"

"No Corporal, thankfully. There's a meeting going on and I thought I'd get out of the way. How did it go with your lot?"

Jones looks at me with tired eyes.

"We gave 'em what for tonight

good'n'proper

but we lost five from Lieutenant Price's platoon

bloody shame. Krauts caught 'em just before the slip out

"

"Damn. "

"Matthew Singer was one of 'em. I saw him get it."

(There is plenty of reaction to this news - all of it miserable. Private Singer had been a popular 'runner' and always had a smart word for the NCOs).

"And Lieutenant Price?"

"No more'n a scratch, Sir

'e's gone over ta see the rest of 'is lot."

We both look up as a shell whistles in out of the night

The wide shelter, with its low ceiling (weighed by tons of earth) feels distinctly tomb-like.

A musky cave.

I try hard not to imagine the initial shock of a direct hit.

Sometimes it can seem that a man is already in his coffin here - just waiting for the actual burial.

There aren't many men who don't tense at the first shriek of a bombardment - even when it is expected.

Jones is one of them. Despite his recent brush with death, he is remarkably calm.

"

.'allo

someone's got 'is gander up."

The explosion is distant, but immediately followed by another, closer by. Several men reach for their helmets. Jones isn't one of them. He seems in fact, oblivious.

"I just 'eared Ol' Charlie's up on another charge, Sir," he says, pulling an indignant face, looking up at me and frowning. "For losing a piece of kit during the last advance, so they tell me."

"Yes. Seems so."

"Lieutenant Yates is a bit keen, in'e?"

Jones takes the bottle of beer held out to him by Ben Harris and tips it to his lips. No one speaks in the time it takes him to drink the ale down and belch loudly.

" Rumour says 'e 'as a dislike for Charlie

maybe even some'ing worse 'an that."

"Really? Sounds like gossip more than rumour. Anyway, I'm sure Lieutenant Gregory and Captain Kensford can handle it between them, Jones. "

He doesn't reply. He only stares at me with red-rimmed eyes. We both know Old Charlie (one of Gregory's platoon) will be charged anyway. Even if it is proved that Yates has made a mistake.

We listen to the bombardment warming up along the front line. The hollow, business-like, boom of the big guns makes men standing about in the damp, airless shelter shuffle their feet.

"I 'eared something else, an' all

." Jones says.

An angry tremble in his voice makes me forget about the cold and the lack of air and even the bombs pounding closer.

"Another rumour, Sir

that Lieutenant Yates snores like a pig."

(This brings with it a few uneasy titters from the men gathered around).

"Just wondered if it were true, Sir."

Jones's eyes remain fixed on mine and hardly waver when someone throws him a piece of rag, which he grabs out of the air and wipes around his face and across the back of his neck, before using on his hands and tossing aside.

Sergeant Norris looks at me, nervously.

It isn't often that Jones lets slip his anger outside of a German trench.

"So, is it true, like?"

"Jones

" Norris whispers, taking a step forward.

"That's alright, Sergeant."

"In fact," Jones continues, "I 'eard 'e snores like a

stinking pig

Sir."

This time no one laughs.

Jones is fired up by his suicidal run back through our lines. His core is still out there dodging bullets and braining men. He is gripped by a rage born out of a strong desire to survive - possibly the most deadly kind of rage there is

battle can do that to any one of us at any time. It can make a man a stranger to himself.

If I've learned nothing else about us as men here in this filthy hell, I've learned that much.

We regard each other, both frowning bitterly.

After a short while Jones looks away and sighs, shaking his head, ashamed of speaking out, no doubt.

I take a deep breath.

"Jones, we all feel bad about Charlie, but you getting yourself put on a charge isn't going to improve things, for him or you

"

"Aye," someone says behind me.

"

and thinking about it, Jones, I'd say Lieutenant Yates snores as loud as Lieutenant Gregory. Which is half as loud as you, if rumour is anything to be believed."

(This gets quite a laugh - it being true).

"That's why they didn't want 'im in the artillery, Sir

can't 'ave 'im kipping anywhere near live shells and such, eh Jonesy?" Harris smirks.

"What

? Ere..." Jones looks only half amused.

"And I would hardly call Mr Yates lazy," I continue, "Right now he seems exceedingly busy to me. Anyway, I'll not hear another word said against him in the trench. Understood?"

"Yes, Sir."

"There's official procedure if you have any grievance, Jones. Right then, if you'll excuse me, I'm going to find a wall to sit against

it's good to see you're still with us, Corporal."

"Thank you, Sir

"

Leaving Jones to it, I move to the back of the shelter.

"Ere y'are, Sir."

It is Sergeant Finch, looking tired and old, as he moves a few folded bits of clothing from the end of a pallet in the corner.

"Thank you, Sergeant."

I sit back, trying not to notice the one or two odd looks being cast my way.

No doubt there are men here asking themselves what an officer might be doing in their non-commissioned midst, barely awake and only half dressed. Especially when they themselves would jump at the chance to see the bombardment out over in the officer's shelter.

Most give me a nod by way of welcome. All look by varying degrees, haggard - as I've no doubt I do myself.

I listen to shells falling further up the line. Around me the men listen too.

"Sounds like Lieutenant Price's lot are copping that. Poor sods."

"Rather them than me."

"You always was an honest man, Stan."

Someone enters the shelter and I feel a cool rush of air cross in front of me.

It is Miltcher, edging into the room, grinning. "Glad to see you back, Corporal Jones."

"Had money riding on it did you, lad?"

(This got quite a laugh from the men, but Milcher looked mortified).

"Just wondered how it went, Corp."

"Well

I'll tell you

"

"Shut that bloody flap, Milcher and 'ere, since when did you 'ave a stripe?"

"Ahhhh, let the lad stay."

"He like's a night-time story, does young Milcher."

"Shut up 'n let Jones tell it, f' Christ sake."

"Go on Jones

"

"

Lady luck was on our side tonight, lads

I don't mind saying

"

"What happened, Jonesy?"

"Well, it were when we were 'eading back

"

He stops and looks up, "Oy oy

"

Men who are standing, instinctively duck as the scream of a falling shell drops towards us, landing close enough to bump the ground beneath the boards and bring a pattering of earth down from over our heads.

"Jeeesus."

"Not in ours

sounds like it fell in supply," someone says.

"A big'n, then."

"You must o' got 'em mad, Jonesy."

"They're mad alright

"

"What d'you do? Piss in their boots?

Ha! Nah, it were on the way back

some Jerry sent a canon shell right over our 'eads

a f*cking beauty it were

a Bob Crompton special - sweeper's long ball

timed it perfect

blew a bleedin' great 'ole in our defences

.just before we got to 'em

clean through we went, without a scratch

said a quick thank you an' all

bullets chasing our arses the 'ole bloody way."

"Cor, someone weren't 'alf swearing, I bet."

"I saw Bob Crompton play once. He's a Right Back."

"What

right back in the changin' rooms?"

'Ah, shut ya trap."

Jones is passed a lit woodbine, which he takes with a nod of thanks and immediately draws on, before trapping in one side of his mouth with a sullen proficiency.

Smiling, his cigarette clamped between his teeth, he looks up. For a moment he appears as any normal twenty-three year old back home in the pub, smiling at his pals.

"Nearly copped me ticket west, boys

but some Kraut must love me, eh?"

"Well it can't be 'cos he got a close look at your face."

It is Ned Richards, looking twice as mud-splattered as Jones, his teeth exposed behind a wide grin, a fresh white bandage wrapped tight around his brow.

"What kept you, Ned?" Someone calls out.

"Couldn't run for laughing, that's what

busy watching Jonesy here doing the knees-up.'

"Ahhh."

"You dodged a few this time, you fast bugger. Oh, hello Sir

. officer's shelter flooded again, is it?"

*

*

They may have had a lucky run through our defences but it looked like Ned Richards had tangled with some wire on the German side.

Those that make it back from such a raid are always marked by cuts of varying degree - from crawling through two rival fortifications of barbed (and sometimes razor) wire; whether or not they can actually dodge bullets.

Volunteers always welcome.

Lying there under that evening sky, I could not imagine a single reason why Tom would want to take part in such a venture. Muscle and might were needed, and good speed across open ground - not an excellence in batman skills.

"Why would you want to do that, Tom?"

"I dunno

maybe I wanted ta be brave

you know, Sir

do something brave."

"And jumping the sandbags

isn't brave? I saw you do some courageous things at Ypres

"

"My three pals all died at Ypres."

"Yes

Yes, I remember."

I also remembered being holed up in a shallow trench about eight miles from our main lines, waiting for reinforcements in wintry weather.

During the night a lad lying out in a Belgian field alone in the dark started calling for a padre. We listened to him knowing that the enemy were watching and waiting for one of us to go out there.

Captain Kensford sent a runner back to try and locate Father Newton, who we knew to be in the general area.

As dawn approached on the horizon, men in the trench grew agitated. No one arrived.

Gradually, the young soldier with the Lancashire accent stopped shouting and began screaming.

Old Tom came and found me.

"Permission to go out there, Sir."

"Don't be ridiculous, Tom."

"I'd like to have your permission, Sir."

"Tom

"

"I knew you'd see it the same way, Sir."

He stood up and saluted me.

"Thank you, Sir. "

*

*

I don't know why I let him go.

Perhaps because I knew he didn't feel he had a choice.

I watched him from the sandbags

as did many others.

We watched the soles of his boots as he crawled away into the dimness.

"What is it with 'im

?" someone asked.

"

Spends 'alf 'is bleedin' time outside the soddin' trenches."

"No talking."

Soon Tom was only a dark shape, blurred and unformed.

Then he disappeared altogether.

We waited.

Eventually, the screaming stopped.

*

*

I lay listening to rats scurry closer with the shadows. Beside me, Tom stirred.

"I 'eared Captain Kensford was going ta offer the raid to you, Sir

. and I thought you'd say yes

I wanted to go along

make sure you didn't get yourself taken prisoner by the bloody Krauts."

For a long time he didn't speak again, then he said

"I've lost a lot of pals in this, you know, Sir. Seen some good men

maybe truly rare men, come and then go

"

"Tom

"

"Go to their deaths in the mud. Like sleepwalkers into a storm."

"Tom

.?"

"Look at that."

I looked up. Blood streaks had begun to seep across a tattered sky.

The sun was falling down again.