No Man's Land - A project

Thanks for taking a look. My work on this project is all experimental - if anyone has any comments, I'd be interested to hear from you.

******************************************

Human history becomes more and more a race between education and catastrophe.

~ H. G. Wells

************************************************************

This first piece is a collection of 'scenes' some written in styles I've never tried before, like present tense, or simple script. Some are more traditional.

The scenes can be read individually, of course.

I'll post a few at a time.

Peace,

Endy

Olga - thanks for the encouragement

The Front

Endymion 2007

**

1

**

Today I tried my hand at carving a recognisable object from a piece of wood.

Do you remember how we used to sit beside father on the step out the back and watch him carve some small and intricate animal for our collection?

He made it look so easy, didn't he? Turning the wood in his hand as he unfolded the secret within. Peeling back the grain with a precise tool - our voices shouting out and making him smile, as we argued over what we could see materializing, like a strange miracle, out of the wood.

No matter what the eventual outcome, Michael would always shout, "donkeeee, donkeeee!"

I can see him now, crouched down in front of us, clapping his baby hands together, his eyes wide with excitement, his shriek ecstatic, "Donkeeee!"

We ended up with a lot of donkeys didn't we?

*

*

Dare I ask what sort of a brother I was to you back then?

I seem to recall wandering off on my own a great deal and leaving you and Michael to play by yourselves.

I'd walk all the way up to Cob's field, where I could look out towards the sea.

Sometimes I experienced a strange sense of standing in a place so mysteriously beautiful, that my singular impression of it could be, in terms of fulfilment, a whole separate lifetime in itself.

That's a powerful memory, and one I try to find strength in, here where beauty can never truly exist

or at least, cannot be interpreted.

Because here, there is no looking forward, only back

and I do look back.

Often to when I first stood alone, searching that pale and faint horizon - in a time when I was still truly innocent.

You see, I didn't know then that everything has its opposite. I saw only the great potential.

When I allowed myself to consider that astonishing distance, I felt closer to my dreams - which were all of adventure.

*

*

Do you remember when Michael was seven and we three walked all the way out to St Michael's Mount? How we laughed to think we might get cut off by the tide - which we nearly did!

If I were an artist, like you

and I wanted to capture that day on canvas- I would search for blues and yellows - the bright yellow of Meadow Vetchling that drew us down to a glittering sea.

Michael was mad with happiness that we'd taken him along with us and ran around all day laughing and whooping. By early evening he was so tired, he could barely stand upright. I had to piggyback him the last stretch home, while you told us ghost stories.

Remember how he fell asleep with his head on my shoulder?

How stunning the sunset was, that saw us home.

It had grown dark by the time we reached the gates and Father was a waiting for us in the doorway.

I expected to be challenged and punished (I don't know why, when it had never happened before) but he took Michael gently from me and carried him off to bed without a word.

There was no punishment - just a timely reminder that I was eleven - old enough to be trusted not to lead you both too far astray on our days out.

Our parents were considered "bohemian" for letting us run wild - but we were happy, weren't we?

While Father dealt with the business of the farm and Mother was off protesting in Westminster, we had our own adventures through the long summers.

I'll never forget the day we nearly got cut off by the tide, but most often I am taken back to the following morning - lying beside you in the grass and comparing the dozens of shells and pebbles we'd each brought home in our pockets the night before.

I can recall with such clear detail, the moment you held a piece of smoothed glass up to the sky and I warned you not to look at the sun through it.

**

2

**

I asked Ben Harris what he thought my carving looked like and after studying it in his hand for a moment - he pulled an uncomfortable face, and said, "Well

I don't rightly know, Sir

. eeer

it looks a bit like

.."

"A bit like what, Corporal?"

"Well

. Could it be a

parrot, sir?"

Parrot indeed!

A few weeks ago, one of Yates' chaps carved himself an iron-cross and painted it with chalk and boot polish.

He wears it too - with a strange, forbidden kind of pride.

I noticed him the other day pulling faces at himself in Lieutenant Gregory's mirror.

Watching him adjust his fake German medal as if it were a bow tie (and he about to go into dinner), made me decidedly nervous.

I suspect he's loosing his mind. Perhaps in a similar way to poor old Tom - but only time will tell.

There's a food shortage again and so we're back to basics. Namely turnips (and bully beef, when we can get it). Bread and biscuits arrive consistently stale - and can often only be eaten if crushed and mixed with water.

It's all rather depressing, actually. Especially when a 'decent meal' consists of cold turnip soup, both watery and unpleasant and sometimes offering-up a couple of strips of tough horsemeat.

You get the general picture, I'm sure.

I think a lot about food.

Smoked kippers, asparagus soup

apple and blackcurrant pie. I crave for fruit so badly, sometimes I dream about it in my sleep.

Extra privileges afforded me and the packets from home do nothing to raise my spirits; in fact I feel strongly that what food there is, should be shared equally amongst all ranks in any given trench.

(Not that I'll be voicing that opinion outside of this journal, of course).

*

*

Today I was called to HQ, by Major Tollet himself.

I found him sitting in a wicker chair on the porch of a renovated 17th Century farmhouse, drinking tea (which he didn't offer me).

A rotund 'gentleman,' with an extraordinarily bias view of all working-class soldiers, Tollet kept me standing to attention while he took the opportunity to sneer at me.

"Lieutenant, this man of yours has visited a field hospital on

three occasions in the last two months, for the simple treatment of

.. what is it?

. Leg ulcers?

"Yes, Sir."

"Leg ulcers

. and you want to send him back for a

fourth time? "

"That's right, Sir."

"You do realise don't you, that he is, in all probability, re-infecting himself? Trying to get out of doing his bit, no doubt. "

I didn't bother explaining to the Major that we couldn't

prise old Frank Harper off the front line if we wanted - and as for

doing his bit- Harper had done more than that at Ypres last year.

"My dear boy

. allow me to enlighten you," Tollet said coldly, leaning forward to place his cup and saucer on a low table. I watched him sit back and settle himself once more in the chair, checking meanwhile to make sure he had my full attention.

He did.

Even the King's pinkish face, glaring down at me from its gold frame just above his head, could not draw my eye.

"It's imperative that you understand one thing at least," Tollet said, as if I was incapable of more than that.

"Your men

will take advantage of you Lieutenant, at every opportunity, wherever they are able

it's in their nature."

I opened my mouth to respond, but he held up a finger.

"

If you allow them."

He feigned patience.

"It's no good

. mollycoddling them, you know. They won't thank you for it

not if they're dead. You've got to toughen them up!"

He made a fist (presumably to demonstrate how tough 'tough' should be).

"The best cure for cowardice is strict discipline

regulation. Let your man know we're onto him

.."

"Yes, Sir."

Tollet raised a finger and pointed at some steps leading out to a cobbled yard and the gates beyond, "That's all - off you go."

Of course, Harper isn't a coward. He isn't even suffering from low morale (well, no lower than the rest of us) - he's suffering from leg ulcers, caused by a bad diet.

We hear lots of excuses, of course - stories of supplies failing to get through due to some unexpected attack by the enemy or whatever. They ask us to be patient - there is a war on after all (as if we didn't know) - but one thing is certain - the Majors and Generals aren't tightening their belts any, you can be sure of that.

**

3

**

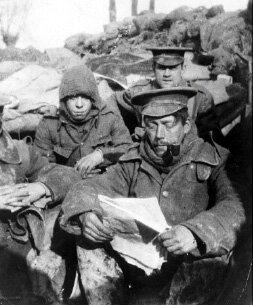

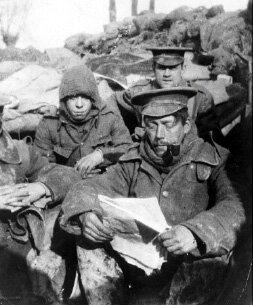

Today we are reclined at The Ritz (a sign on a post says so).

Here the frontline trench runs like any other, but there is very little action to be seen.

The Germans dug in first here (as usual) and built their trenches on the higher ground. In contrast, we are tucked in close to the wood.

It's mostly a defensive position, held in close proximity to the enemy. So close, that all along this stretch, we sit within shouting distance of each other and yet sniper deaths are rare.

Of course, being in a less volatile sector does have its setbacks. We're the last to get re-supplied here and have no friendly town close by. Sometimes we're entirely cut off by flooding of the support trench and nothing gets done for days.

You could say that our demands are not a priority.

No one wants an order to come down for an attack on the German trenches. We've got entirely used to them being a part of out routine.

We leave each other alone. We're fixed for the winter and apart from Artillery having an occasional 'go' at one side or the other - things are quiet on this stretch.

Of course, the trench system runs on a rotation basis, with platoons doing a stint in the busiest front line trenches and then a stint in supply or support and occasionally completely off line for rest.

Captain Kensford tries to see to it that every platoon gets equal duties in sector 1- especially a turn at the Ritz (which means more or less, 'having a breather').

Thing is, the men have started complaining.

All day (and sometimes at night) we have to put up with an inescapable accordion 'player'. A German we've nicked-named Mad Winnie - as in 'Winnie's got the wind up again.'

I don't know why the Hun put up with him, but they do.

Perhaps they don't know what else to have done with him, but let him sit in his usual position, playing his five favourite tunes over and over again.

I once heard one of our boys scream out, "Shut-up! For Christ's sake, please

just

stop."

And for a few incredible moments it did.

I looked up during that pause and saw a pair of ducks flying over us, heading towards the Belgium boarder.

I watched them and wondered if they saw us down here. Men embroiled in a cruel game of fortune, waiting to see which team would go mad or die first.

Then it crept back in, softly rising.

The German accordionist continued undaunted and eventually (in desperation) we got a Scottish chap down from HQ to play the pipes at the bastard (nice and loud - a highland battle-song) - but the soddin' Kraut seemed to know the tune and simply joined in - with gusto!

We could hear the Germans laughing over there like children and after a bit, a few of our men joined in.

Some German wag shouted out to us, "You Tommy, you must learn from Fritz -ya? Pack mud in ears, voila! Ya? Ha, ha."

Ben Harris yelled back, "Terribly sorry old chap, 'fraid we can't hear you

some idiot with a bloody accordion

. can you stand up and repeat that, please? "

Then came the almighty roar of Sergeants on both sides of the line, reminding the two conversationalists that parlour talk with the enemy is strictly forbidden.

**

4

**

It's strange how quickly we are adapting to our circumstances here in the trenches. After a year at the front, we have forgotten there is a clean and sane world out there where horror does not wait patiently around every corner.

We have forgotten who we once were, when we were free men, with each a dream.

We've become numbed to many aspects of trench life - as Lieutenant Yates revealed, when he arrived as a replacement back in August.

There was a sense of disquiet as soon as he appeared.

Lieutenant Gregory and I had been hoping for a fellow 'thinker' rather than the Eton-educated, by-the-book traditionalist who turned up in our sector.

Fresh from Sandhurst, Yates (tall, slim and immaculately dressed) spent his first three days in the busiest frontline trench with one hand pressed to the lower half of his stricken face.

Our dead lay sprawled like shot cattle out in the fields - and it had been that way for months. There they remained, English and German, abandoned together in varying degrees of putrefaction under a warm August sun.

This, along with the sharp stink of latrines (bad enough to take the breath away) and piles of rotting sandbags, caused Yates no end of misery.

Nothing was as he had imagined it.

What glory could be found here, in this muddy field of dead filth?

Yates wanted French virgins to rescue from German brutality. He wanted his picture taken with cheering French villagers - or some great chance to impress Generals.

In reality, he wanted recognition - as long as it didn't involve getting dirty.

I offered him my hand to shake when first we met and he declined; raising his own in a small warding off gesture, a grim little smile on his face.

I could see him eyeing the infected insect bites on my neck with plain disgust.

It's true the lice are terrible, revolting and unbearable, but there is little we can do - for we cannot eradicate them - and that's a fact we've learnt to live with.

Likewise the rats, which just keep coming, no matter how many we kill.

While both species breed and multiply in large, unstoppable numbers, we men on the other hand, kill ourselves in opposition, here in a strip of land that has quickly ground itself into a very real and stagnant nightmare.

The lice feast on us while we live and the rats move in when we're dead. We exist in this hell with them, fighting for our survival, just like them.

Yates took in the state of our surroundings with a horrified eye, but it was the smell of unwashed men that really seemed to offend him.

Especially his fellow officers, who he obviously thought should have a bit more pride (or privilege).

"I say, this is an absolute scandal."

The words were meant for me (this was before he found out I was a farmer's son and decided not to engage in conversation with me at all - unless strictly necessary) as we stood in the officer's dugout and he looked around in horror.

The cave did appear strangely Elizabethan. Dried mud clung like dust to most surfaces.

Over in the corner, Captain Kensford (nothing more than a bundled shape) was snoring contentedly. Today was the first chance he'd had to get his head down in thirty something hours.

"No officer should be expected to sleep in this

.. in this

this

.."

Not surprisingly, Yates was unable to finish the sentence.

Words failed him. He looked strangely outraged to find an Officer asleep during the day and kept glancing over at Kensford, as if the man were insulting him by being unaware of his arrival.

At that point I still felt some sympathy for Yates, after all, I hardly knew him

He didn't know he was looking at his CO asleep in the corner, he was new to the game and it would take him a while to come to terms with the realities.

Then he looked at me, a frown creasing his face. "My God, it's

.

filthy. The smell alone

"

I could hardly fail to recognise the disgust.

I found myself sniffing at the air.

"Actually, it's really not too bad at the moment - if we get heavy rain, it fills up like a sour pond

It can flood in just a few hours. You wake up you're sharing your bed with the rats. It starts to smell quite repulsive in here then

"

"I don't think I understand

"

(He really looked like he didn't).

"Don't worry, you will."